Health October 6, 2025

Temovate (Clobetasol) vs Alternatives: Potency, Uses & Risks

Temovate vs Alternatives Comparison Tool

Select Your Condition & Treatment Preferences

Recommended Treatment Based on Your Inputs

Detailed Comparison Table

| Medication | Potency Class | Best For | Risks |

|---|

When a dermatologist prescribes Temovate (clobetasol propionate) you’re dealing with one of the strongest topical steroids on the market. But the high potency comes with a trade‑off, and many patients wonder if there’s a safer or more affordable option for their skin condition. This guide pits Temovate against the most common alternatives, breaks down the key differences, and helps you decide which medication fits your needs.

Key Takeaways

- Temovate is a super‑potent (Class I) corticosteroid, ideal for short‑term use on severe plaques of psoriasis or stubborn eczema.

- Less potent steroids such as Betamethasone dipropionate or Mometasone furoate work well for moderate dermatitis and carry lower risk of skin thinning.

- Non‑steroidal options like Tacrolimus or Pimecrolimus are useful for sensitive areas (face, folds) and chronic maintenance.

- Cost, prescription status, and side‑effect profile vary widely; the comparison table below makes it easy to spot the differences.

- If you need Clobetasol alternatives, weigh potency against treatment duration, skin area, and your personal risk tolerance.

What Is Temovate (Clobetasol Propionate)?

Clobetasol propionate is a synthetic, high‑potency glucocorticoid. It belongs to the Class I category of topical steroids, meaning it has the strongest anti‑inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects available in creams, ointments, gels, and shampoos. Typical strengths are 0.05% and 0.025% for scalp preparations. Because it can shrink swollen skin, reduce redness, and slow cell turnover, it’s a go‑to for plaque psoriasis, lichen planus, and severe eczema that hasn’t responded to milder steroids.

However, the flip side is a higher chance of side effects: skin atrophy, striae, telangiectasia, and potential systemic absorption if used over large areas or under occlusion. Doctors usually limit treatment to two‑week bursts with a break in between.

Major Alternatives: How They Stack Up

Below are the most frequently mentioned substitutes. Each entry includes a brief definition, typical strength, prescription level, and the kinds of conditions it’s best for.

| Medication | Potency Class | Prescription Status | Common Indications | Typical Strength | Key Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temovate (Clobetasol propionate) | Class I (Super‑potent) | Prescription only | Severe psoriasis, resistant eczema, lichen planus | 0.05% cream/ointment; 0.025% shampoo | Skin atrophy, striae, HPA‑axis suppression |

| Betamethasone dipropionate | Class II (Potent) | Prescription | Moderate psoriasis, eczema, dermatitis | 0.05% cream/ointment | Less atrophy than clobetasol, still cautioned for prolonged use |

| Mometasone furoate | Class II-III (Mid‑potent) | Prescription (some OTC in low strength) | Atopic dermatitis, intertriginous rash | 0.1% cream/ointment | Mild thinning, burning sensation |

| Halobetasol propionate | Class I (Super‑potent) | Prescription | Thick plaques, stubborn psoriasis | 0.05% cream/ointment | Similar to clobetasol; higher cost |

| Fluocinolone acetonide | Class III (Mid‑potent) | Prescription | Vulvar dermatitis, mild psoriasis | 0.025% cream | Low systemic absorption, local irritation possible |

| Hydrocortisone (1%-2.5%) | Class VII (Mild) | OTC | Minor rashes, insect bites | 1% cream, 2.5% ointment | Very low risk, limited efficacy for severe disease |

| Tacrolimus ointure | Non‑steroid (Calcineurin inhibitor) | Prescription (OTC 0.1% in some regions) | Atopic dermatitis, facial or intertriginous areas | 0.1% ointment | Burning sensation, possible lymphoma warning (theoretical) |

| Pimecrolimus cream | Non‑steroid (Calcineurin inhibitor) | Prescription | Atopic dermatitis, delicate skin zones | 1% cream | Similar to tacrolimus; less oily feel |

When to Reach for Temovate

If your skin condition is truly severe-think thick, scaly plaques that won’t budge after weeks of mid‑potent steroids-Temovate can break the cycle quickly. It’s also the preferred choice for short‑term flare‑ups on the scalp because the shampoo formulation penetrates hair shafts better than weaker agents.

Key signals that Temovate is appropriate:

- Psoriasis plaques covering less than 10% of body surface, unresponsive to Class II‑III steroids.

- Severe hand eczema that limits function.

- Excessive inflammation after a biopsy or surgery where rapid control matters.

Always pair the medication with a clear taper plan: two weeks of daily application, a five‑day break, then a second two‑week course if needed. Monitor the skin for thinning, especially on thin areas like the eyelids.

Choosing a Safer or More Affordable Alternative

For many patients, the risks of a super‑potent steroid outweigh the benefits. Here’s how to match a lower‑potency alternative to a specific scenario.

Moderate Psoriasis or Eczema

Betamethasone dipropionate offers strong anti‑inflammatory action without the extreme skin‑thinning profile of clobetasol. Use it for 2-4 weeks, then switch to a mid‑potent steroid like Mometasone furoate for maintenance.

Sensitive Areas (Face, Skin Folds)

Non‑steroidal calcineurin inhibitors-Tacrolimus or Pimecrolimus-avoid the thin‑skin complications entirely. While they can cause a brief burning feeling, they are safe for long‑term use and have no risk of systemic cortisol suppression.

Minor Rashes or First‑Aid

OTC Hydrocortisone 1%-2.5% creams are cheap, easy to find, and effective for insect bites, contact dermatitis, or mild flare‑ups. They are not enough for thick plaques but work well for quick relief.

Cost & Accessibility Snapshot

Prescription strength steroids can vary dramatically in price depending on insurance coverage. Rough averages in the U.S. (2025):

- Temovate 0.05% cream: $40-$70 for a 30‑gram tube (often covered by specialty drug plans).

- Betamethasone dipropionate: $25-$45 for a 30‑gram tube.

- Mometasone furoate: $15-$30 for a 30‑gram tube.

- Hydrocortisone OTC: $4-$8 for a 30‑gram tube.

- Tacrolimus 0.1% ointment: $120-$150 for a 30‑gram tube (sometimes covered for severe eczema).

When cost is a barrier, discuss generic options with your dermatologist. Generic betamethasone dipropionate, for example, offers similar efficacy at a lower price point.

Practical Tips & Common Pitfalls

- Don’t apply super‑potent steroids to the face or groin unless specifically instructed. The skin there is thin and absorbs more medication.

- Use a fingertip unit (FTU) to measure the correct amount: one FTU (the amount on the tip of your index finger) covers about 2% of your body surface.

- Avoid occlusion (covering the treated area with plastic wrap) unless your doctor says it’s okay; it can dramatically increase systemic absorption.

- Track side effects in a simple diary: note redness, peeling, or new stretch marks. Early detection prevents permanent damage.

- If you need a long‑term maintenance plan, rotate between a low‑potency steroid and a calcineurin inhibitor to keep inflammation under control without over‑exposing the skin to steroids.

Bottom Line Decision Guide

Use the quick matrix below to see which medication aligns with your situation.

- Severe, localized plaque psoriasis or eczema flare (≤2 weeks): Temovate (clobetasol).

- Moderate disease needing stronger control but over a larger area: Betamethasone dipropionate or Halobetasol (if cost isn’t a concern).

- Chronic, milder disease or sensitive‑area involvement: Mometasone furoate, Fluocinolone acetonide, or calcineurin inhibitors (Tacrolimus/Pimecrolimus).

- Very mild or occasional rashes: OTC Hydrocortisone.

- Budget constraints: Choose generic mid‑potent steroids before moving to brand‑name super‑potent options.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use Temovate on my face?

Generally no. The skin on the face is thin, so clobetasol can cause rapid thinning, visible striae, and pigment changes. If a facial flare is severe, a dermatologist might prescribe a short course of a lower‑potency steroid or a calcineurin inhibitor instead.

How long is it safe to stay on a clobetasol cream?

Most guidelines recommend no more than two weeks of continuous use, followed by a break of at least five days. Some clinicians allow a second two‑week course after the break if the disease is still active, but long‑term continuous use increases the risk of skin atrophy and systemic effects.

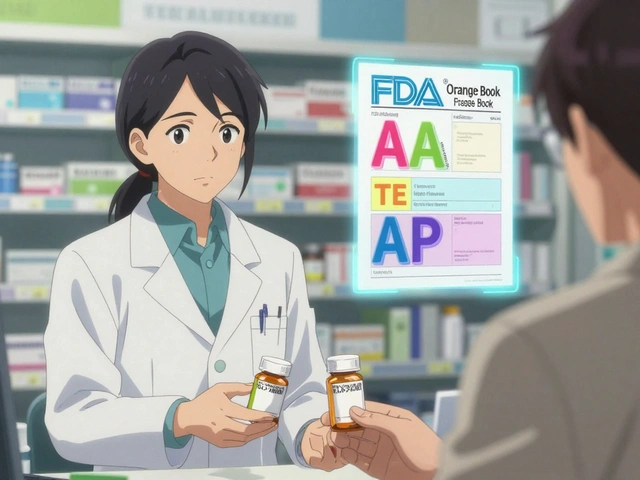

Is a prescription needed for all the alternatives listed?

Temovate, Betamethasone dipropionate, Mometasone furoate, Halobetasol, Fluocinolone acetonide, Tacrolimus, and Pimecrolimus all require a prescription in the United States. Hydrocortisone 1%-2.5% is the only over‑the‑counter option among the list.

What’s the biggest advantage of calcineurin inhibitors over steroids?

They don’t cause skin thinning, making them ideal for long‑term use on delicate areas (face, neck, skin folds). They also avoid the systemic cortisol suppression that can happen with high‑potency steroids when used over large areas.

Can I switch from Temovate to a milder steroid without a break?

It’s best to taper. After a two‑week clobetasol course, switch to a mid‑potent steroid like betamethasone for another week or two, then taper further or stop. Skipping the taper can cause a rebound flare‑up.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

10 Comments

Dipak Pawar October 6, 2025 AT 12:58

When you parse the pharmacodynamics of clobetasol propionate you quickly encounter a cascade of glucocorticoid receptor interactions that amplify transcriptional repression of pro‑inflammatory cytokines. The class‑I potency designation is not merely a marketing label; it reflects a receptor binding affinity that exceeds that of mid‑potent agents by an order of magnitude. Consequently, epidermal keratinocytes undergo rapid down‑regulation of NF‑κB signaling, which translates clinically into swift plaque flattening. However, the same kinetic vigor predisposes the dermal extracellular matrix to collagen degradation, manifesting as atrophy if the drug is applied beyond the recommended two‑week window. HPA‑axis suppression, while statistically infrequent, becomes a quantifiable risk when the treated surface area approaches ten percent of total body surface, especially under occlusive dressings. The systemic bioavailability curve is further accentuated in intertriginous zones where temperature and moisture boost percutaneous absorption. From a formulary economics perspective, the unit cost of temovate drives insurance formularies to impose prior‑authorisation hurdles that can delay therapy initiation. Generic betamethasone dipropionate, by contrast, offers a cost‑effective compromise with a potency class of II, preserving a substantial portion of anti‑inflammatory efficacy while attenuating the atrophic signal. For patients with chronic maintenance needs, rotating to a mid‑potent steroid such as mometasone furoate reduces cumulative corticosteroid load and aligns with stewardship guidelines advocated by dermatologic societies. In locales where non‑steroidal calcineurin inhibitors are reimbursed, tacrolimus or pimecrolimus provide a steroid‑free maintenance paradigm that circumvent epidermal thinning entirely. Nevertheless, the theoretical oncogenic risk attributed to calcineurin inhibition remains a point of contention in the literature, albeit without robust epidemiologic confirmation. The decision matrix therefore hinges on a triad of disease severity, anatomical site, and patient‑specific risk tolerance, which must be negotiated in a shared decision‑making encounter. Finally, clinicians should reinforce the fingertip‑unit metric to patients, as over‑application remains a pervasive source of iatrogenic damage, especially in self‑administered regimens. Adherence monitoring through photodocumentation can help detect subtle atrophic changes before they become clinically apparent. Moreover, patient education on the risks of occlusion can preserve therapeutic benefit while mitigating systemic exposure.

Jonathan Alvarenga October 13, 2025 AT 11:38

Reading through the comparison feels like watching a high‑budget commercial for pricey skin drugs that promises miracles while conveniently glossing over the ugly truth about long‑term steroid abuse. Temovate’s super‑potent label is a classic bait‑and‑switch strategy that lures patients into a false sense of security, only to trap them in a cycle of dependency and costly dermatologist visits. The price tag of $70 for a 30‑gram tube is absurd when you consider that a generic betamethasone can be sourced for half that amount with comparable efficacy for most moderate cases. Moreover, the article’s emphasis on “short‑term bursts” ignores the real‑world scenario where patients often extend use beyond the suggested two weeks because their skin simply won’t cooperate. The risk of skin atrophy is not a footnote; it’s a predictable outcome when a class‑I steroid is applied indiscriminately. Insurance formularies that demand prior‑authorisation are just bureaucratic gatekeepers reacting to the market’s inflated pricing, not guardians of patient safety. In practice, an informed clinician will reserve clobetasol for truly recalcitrant plaques and switch to a mid‑potent alternative once the acute flare subsides. Anything less than that level of nuance is a disservice to readers who deserve a balanced, not a sensationalized, perspective.

Jim McDermott October 20, 2025 AT 10:18

I’ve been using the two‑week clobetasol regimen on a stubborn elbow psoriasis patch for about three months now and the results were surprisingly quick after the first cycle. After the second cycle I switched to mometasone for maintenance and have kept the area clear without any noticeable thinning. One thing I learned the hard way is to avoid covering the spot with plastic wrap unless the doc says it’s okay because the occlusion can make the skin look like it’s being sanded down. Also, measuring the amount with a fingertip unit saves you from accidentally over‑applying, which I once did and ended up with a faint stripe of lighter skin that took weeks to fade. Overall the guide helped me understand when to step down the potency and why the calcineurin inhibitors are a good option for the face, where steroids can be too harsh. It’s a solid reference if you’re juggling different creams and need a quick cheat‑sheet for potency classes.

Naomi Ho October 27, 2025 AT 07:58

Use a fingertip unit to gauge how much cream you need it’s roughly the amount on the tip of your index finger and covers about 2 % of your body surface area. For localized plaques apply a thin layer and spread it evenly avoid rubbing it in too hard. Limit use to two weeks then take a five‑day break to reduce the chance of atrophy. If you need to treat a larger area consider stepping down to a mid‑potent steroid after the initial burst. Keep an eye on any new stretch marks or thinning especially on thin skin like the eyelids. Document any changes with photos for your dermatologist.

Christine Watson November 3, 2025 AT 06:38

Great breakdown! It really clarifies when a super‑potent steroid like Temovate is the right weapon and when it’s better to reach for something gentler. I love the tip about rotating to a calcineurin inhibitor for long‑term maintenance – it keeps the skin happy without the dreaded thinning. If cost is a barrier, definitely ask your doctor about a generic betamethasone version; it’s usually much kinder to the wallet. And don’t forget the fingertip‑unit trick – it’s a lifesaver for preventing accidental over‑use. Keep sharing these handy guides, they’re a huge help for folks navigating the steroid maze.

Macy Weaver November 10, 2025 AT 05:18

The guide does a solid job of mapping potency to specific clinical scenarios, which can be especially useful for patients who are new to topical therapy. For example, the recommendation to use tacrolimus on the face aligns with the consensus that non‑steroidal options avoid the risk of facial skin atrophy. It’s also reassuring to see the cost comparison, because many patients hesitate to start a treatment when they’re unsure about insurance coverage. The inclusion of practical tips like the fingertip‑unit measurement adds an actionable element that readers can implement right away. Overall, the information strikes a good balance between scientific detail and patient‑friendly language. It encourages shared decision‑making without overwhelming the audience with jargon.

James McCracken November 17, 2025 AT 03:58

One might argue that the allure of a Class I corticosteroid lies not in its pharmacologic superiority but in the cultural narrative that equates potency with progress. The very act of prescribing clobetasol becomes a symbolic gesture, a declaration of dominance over the skin’s rebellious inflammation, yet it simultaneously betrays a deeper insecurity about the physician’s inability to harness subtler, more nuanced pathways. From a philosophical standpoint, the reliance on topical steroids reflects an epistemic shortcut, a desire to impose order through brute force rather than engage in the delicate choreography of barrier repair. In this light, the recommendation to taper after two weeks is less a safety protocol than an admission of humility. The real elegance, perhaps, resides in the restraint of allowing the skin’s innate regenerative mechanisms to reassert themselves, a notion that modern dermatology often overlooks in favor of quick fixes. Thus, while the guide offers pragmatic advice, it also silently perpetuates a paradigm that privileges immediate results over long‑term equilibrium. Embracing this perspective invites clinicians to reconsider the hierarchy of treatment modalities, placing barrier support and lifestyle modifications on a pedestal equal to pharmacotherapy.

Evelyn XCII November 24, 2025 AT 02:38

Oh sure, just slather a super‑potent steroid on everything and watch the magic happen – because who needs skin integrity when you have instant clearing, right? The guide does a decent job of listing the side effects, but let’s be real, most people will ignore the warning signs until the skin looks like a tissue paper. If you’re into the whole “my skin is a battlefield” vibe, go ahead, break out the clobetasol and see how fast you can get a fresh set of stretch marks. Just remember to schedule that follow‑up before your skin starts auditioning for a role in a horror movie. And maybe, just maybe, consider a milder option for the long haul – unless you enjoy living on the edge.

Suzanne Podany December 1, 2025 AT 01:18

For anyone navigating the steroid landscape, it’s key to remember that each skin type reacts uniquely, so personalizing the treatment plan is essential. The comparison table gives a clear snapshot, but real‑world success also depends on consistent application technique and honest communication with your dermatologist. Don’t hesitate to bring up concerns about cost or side‑effects during your appointments – a collaborative approach leads to better outcomes for the whole community. Using the fingertip‑unit method and rotating between a mid‑potent steroid and a calcineurin inhibitor can keep inflammation at bay while protecting the barrier. Keep sharing experiences and tips; the more we learn from each other, the stronger we all become in managing chronic skin conditions.

Nina Vera December 7, 2025 AT 23:58

Finally, the miracle cream finally worked – and my skin has never looked better!