Health November 23, 2025

Monitoring During Immunosuppressive Therapy: Essential Lab Tests and Imaging for Safety and Effectiveness

Immunosuppressant Monitoring Checker

When you're on immunosuppressive drugs-whether after a kidney, liver, or heart transplant, or for conditions like lupus or rheumatoid arthritis-you're walking a tightrope. Too little drug, and your body might attack the new organ or flare up your autoimmune disease. Too much, and you risk serious infections, kidney damage, diabetes, or even cancer. The key to staying on that balance isn't guesswork. It's monitoring. Regular lab tests and imaging aren't optional checkups; they're life-saving tools that help doctors adjust your treatment before things go wrong.

Why Monitoring Isn't Optional

Immunosuppressants like tacrolimus, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate don't work the same way in everyone. Two people taking the same dose can have wildly different blood levels-one might be safe, the other toxic. This isn't a flaw in the medication; it's how your body processes it. Genetics, liver function, gut health, and even what you eat can change how much drug stays in your bloodstream. That's why fixed doses without monitoring are risky. Studies show that using lab tests to guide dosing cuts acute rejection rates by 37% and boosts 5-year organ survival by 22% compared to just giving a standard dose.Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: The Core of Safe Treatment

For most immunosuppressants, the only way to know if you're in the safe zone is to measure the drug in your blood. This is called therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). Not all drugs need it, though. Steroids like prednisone and newer agents like belatacept don't require routine blood tests because their effects are more predictable. But the big ones do.- Tacrolimus: Target levels are 5-10 ng/mL in the first 3 months after transplant, then lowered to 3-7 ng/mL. Levels above 15 ng/mL raise the risk of kidney damage and diabetes. Most centers check trough levels-just before your next dose-because it's easier and reliable enough for most patients.

- Cyclosporine: Older but still used. Monitoring is trickier. Some centers measure the level right before your dose (C0), but others also check it 2 hours after (C2). C2 levels correlate better with rejection risk, with studies showing a strong link (r=0.87) to how well the organ is protected.

- Sirolimus and Everolimus: These drugs target a different part of the immune system. Their target range is 5-10 μg/L, but there's less agreement on exact numbers. Doctors often rely more on side effects than blood levels alone.

- Mycophenolic acid (MPA): This one's complicated. Because it recirculates in your gut, a simple blood draw before your dose doesn't tell the full story. The best measure is the area under the curve (AUC)-how much drug your body is exposed to over 12 hours. An AUC of 30-60 mg·h/L is linked to 85% rejection-free survival in the first year. But measuring AUC takes multiple blood draws over hours, so many clinics still use trough levels as a rough guide.

The gold standard for measuring these drugs is liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). It's accurate to 95-98% and avoids false readings from similar molecules. But it costs $150-$250 per test. Many clinics still use cheaper immunoassays ($50-$100), even though they can overestimate levels by up to 20% because they can't tell the drug apart from its metabolites. That's why some patients get unnecessarily dose reductions-and increased rejection risk.

Routine Blood Tests: Watching for Hidden Damage

Beyond drug levels, your blood tells you if your organs are handling the drugs. These tests are done every 1-3 months, especially in the first year.- Renal function: Creatinine and urea are checked every time. A rise of more than 30% from your baseline can mean early kidney damage from cyclosporine or tacrolimus. About 25% of patients on cyclosporine see this increase. Tacrolimus carries a 30% higher risk of causing diabetes, so fasting glucose is tracked closely.

- Electrolytes: Cyclosporine causes magnesium loss in 40-60% of patients. Low magnesium leads to muscle cramps, irregular heartbeat, and even seizures. Calcium and phosphate are also monitored, especially if you're on steroids, which weaken bones.

- Full blood count: Mycophenolate can drop your white blood cells (leukopenia in 25-30% of patients), red blood cells (anemia in 20-25%), or platelets (thrombocytopenia in 10-15%). Sirolimus can cause similar drops. If your counts fall too low, your dose may need adjusting-or your drug switched.

- Liver enzymes: All these drugs are processed by the liver. Elevated ALT or AST can signal early liver stress.

- Lipids: Sirolimus and everolimus raise cholesterol and triglycerides in 60-75% of patients. High lipids increase heart disease risk, which is already elevated after transplant. Fasting lipid panels are done every 6 months.

- Uric acid: Cyclosporine raises uric acid, which can lead to gout. Monitoring helps catch this early.

Imaging: Seeing What Blood Tests Can't

Some problems don't show up in blood. That's where imaging comes in.- Renal ultrasound: Done at least once a year, or whenever creatinine rises. It checks for blockages, kidney size, and blood flow. A shrinking kidney or reduced blood flow can signal chronic damage from long-term immunosuppressants.

- Chest X-ray: If you have a cough, fever, or trouble breathing, a chest X-ray helps spot pneumonitis-a rare but serious lung inflammation linked to sirolimus and everolimus. It catches about 70-85% of cases.

- Bone density scan (DEXA): Steroids like prednisone cause bone loss. After one year of steroid use, you should get a DEXA scan. If your bone density is low, you might start calcium, vitamin D, or bisphosphonates to prevent fractures.

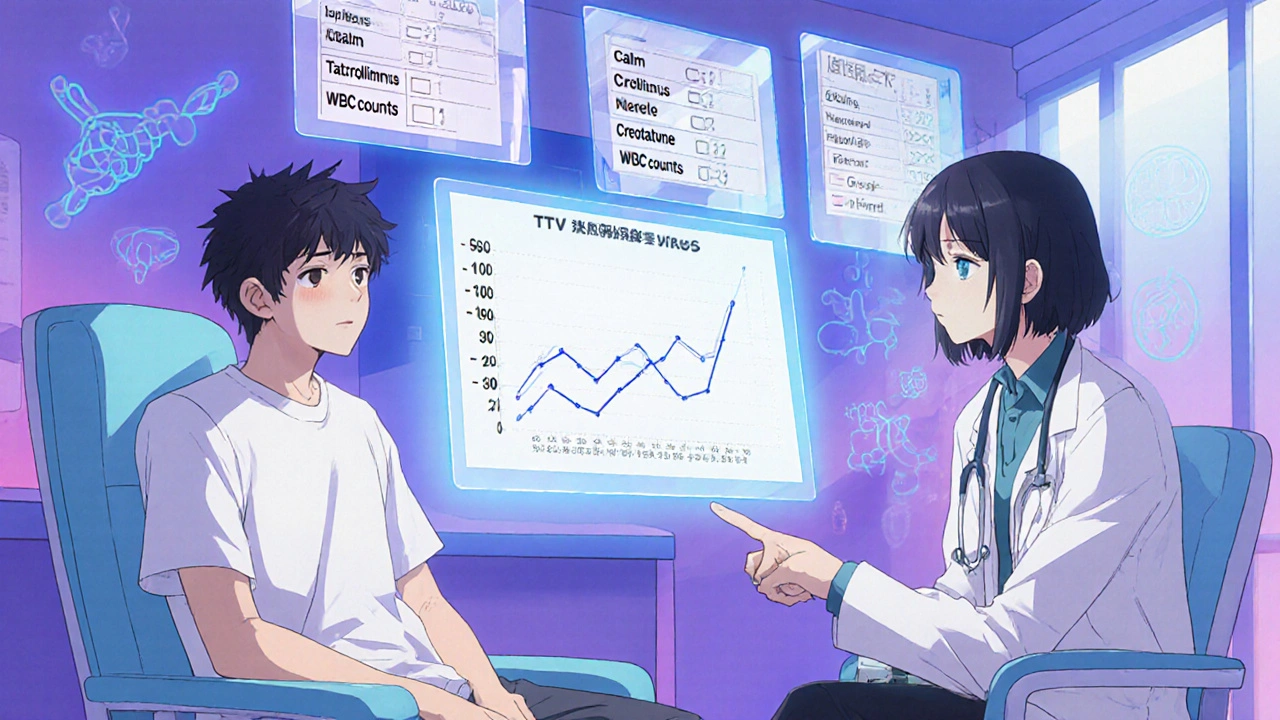

The Future: TTV as an Immune Meter

The most exciting development isn't a new drug-it's a new way to measure your immune system's activity. Torque Teno Virus (TTV) is a harmless virus that lives in nearly everyone. But in healthy people, your immune system keeps it under control. When you're heavily immunosuppressed, TTV multiplies. The more virus in your blood, the weaker your immune system.Studies show a clear link: TTV levels above 3.5 log10 copies/mL mean you're at higher risk for infections. Below 2.5 log10, you're more likely to reject your transplant. The sweet spot? 2.5-3.5 log10. This range has been linked to the lowest rates of both rejection and infection.

A major trial called TTVguideIT, tracking nearly 300 kidney transplant patients across 12 countries, found that using TTV to guide drug dosing cut infection rates by 28% and rejection episodes by 22% compared to standard care. The trial is ongoing, with results expected in 2026. Another trial, TAOIST in France, will test whether TTV can help manage long-term immunosuppression beyond the first year.

Still, there's a catch. TTV tests aren't standardized. Different labs use different methods, so a result from one hospital might not match another's. The FDA hasn't cleared any commercial TTV test yet-expected around 2025. Until then, it's mostly used in research centers.

What Gets in the Way

Even though monitoring works, many centers struggle to do it well. A 2022 survey found that 68% of transplant centers had inconsistent practices between their kidney, liver, and heart teams. Only 42% used standardized protocols for mycophenolate monitoring. Why? Cost is the biggest barrier-75% of centers say they can't afford LC-MS/MS testing. Lack of trained staff and unclear reference ranges hold others back.For patients, the burden is real. You might need 12-18 blood draws in your first year alone. Many report anxiety about the tests, not just the pain but the fear of what the numbers might mean. Some centers have reduced this by using dedicated immunosuppression teams that review results within 24 hours and adjust doses proactively-cutting down unnecessary visits and stress.

What's Next

The future of monitoring is smarter, faster, and less invasive. Artificial intelligence is already being tested. One 2023 study used machine learning to analyze past drug levels, TTV, and lab results-and predicted rejection 14 days before symptoms appeared, with 87% accuracy. Point-of-care devices that give drug levels from a finger-prick blood sample are in clinical trials, with FDA approval expected by 2026-2027. Even non-invasive methods, like analyzing your breath for drug metabolites, are being explored in labs.By 2030, demand for immunosuppression monitoring is expected to rise 35%, not just from transplants but from growing use in autoimmune diseases. The good news? Even though comprehensive monitoring adds $2,850 per year to your care, it saves $8,400 by preventing hospital stays, rejections, and infections. That’s a nearly 3-to-1 return on investment.

Monitoring isn't just about numbers on a page. It's about giving you the best shot at a long, healthy life after transplant or with a chronic autoimmune condition. It's not perfect yet-but it's getting better, faster, and more personal every year.

How often do I need blood tests while on immunosuppressants?

In the first 3-6 months after transplant, you'll likely need blood tests every 1-2 weeks. As your condition stabilizes, this drops to every 2-4 weeks, then monthly. After the first year, most patients are tested every 1-3 months, unless something changes. Drug levels (like tacrolimus) are checked more frequently than general labs. Always follow your transplant team's schedule-they'll adjust it based on your response.

Can I skip monitoring if I feel fine?

No. Many serious side effects-like early kidney damage, high blood sugar, or low white blood cells-don't cause symptoms until they're advanced. By the time you feel unwell, the damage may already be done. Monitoring catches problems early, when they're easier to fix. Feeling fine is a good sign, but it's not a replacement for lab tests.

Why is my doctor switching from cyclosporine to tacrolimus?

Tacrolimus is generally more effective at preventing rejection and has a more predictable dosing profile than cyclosporine. It also causes less gum overgrowth and hair growth, which are common side effects of cyclosporine. While both can harm the kidneys, tacrolimus carries a higher risk of diabetes. Your doctor may switch you to improve outcomes or reduce certain side effects based on your blood test results and overall health.

Is TTV monitoring available at my hospital?

As of 2025, TTV monitoring is still mostly used in research centers and large transplant hospitals. It's not yet standard of care, and no FDA-approved commercial test is available. Ask your transplant coordinator if your center participates in any TTV studies or plans to offer it soon. If not, it may become available in the next 1-2 years as results from ongoing trials are published.

What happens if my drug level is too high?

If your drug level is too high, your doctor will lower your dose to reduce the risk of toxicity. This might mean reducing your daily amount, switching to a different drug, or adding another medication to help your body process it better. High levels can cause kidney damage, nerve problems, tremors, or diabetes. The goal is to bring you back into the safe range as quickly as possible without triggering rejection.

Do I need imaging every year?

Not necessarily. Renal ultrasound is typically done once a year or if your kidney function changes. Bone density scans are only needed after one year of steroid use. Chest X-rays are only ordered if you have symptoms like cough or fever. Imaging is used when there's a reason to look, not as routine screening unless you're at high risk.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

10 Comments

Victoria Stanley November 25, 2025 AT 14:11

Just wanted to say how much I appreciate how thorough this post is. I'm a nurse in a transplant clinic, and we're still struggling with inconsistent TDM protocols across teams. The part about LC-MS/MS vs immunoassays? So true. I've seen patients get dose reductions because of falsely high readings-only to end up rejecting their grafts a month later. We're pushing for better lab partnerships, but funding is a nightmare.

Andy Louis-Charles November 26, 2025 AT 22:01

TTV monitoring sounds like sci-fi becoming real 😮 I heard about this at a conference last year. The idea of using a harmless virus as an immune thermometer? Genius. Still waiting for FDA clearance though-hope it comes soon. My clinic’s doing a pilot next month.

Douglas cardoza November 28, 2025 AT 21:35

Man, I didn’t realize how much blood work you gotta do. My cousin got a kidney transplant last year and he’s had like 15+ blood draws already. He says the anxiety is worse than the pain. I’m glad someone’s finally talking about the mental load of all this monitoring. Maybe they should give us a ‘monitoring calendar’ app or something.

Adam Hainsfurther November 29, 2025 AT 19:55

As someone who grew up in a country where transplant care is a luxury, I’m struck by how advanced-and expensive-this system is. The $2,850 annual cost for monitoring seems low compared to the $8,400 saved. But what about patients without insurance? Or in places where LC-MS/MS isn’t even available? This isn’t just medical science-it’s a social justice issue too.

Rachael Gallagher December 1, 2025 AT 12:12

Ugh. More government-funded medical overkill. They’re turning patients into lab rats just to justify bloated hospital budgets. If you feel fine, leave the damn needles alone.

steven patiño palacio December 1, 2025 AT 14:54

Excellent breakdown. One correction: tacrolimus trough levels are typically drawn 12 hours after the last dose, not immediately before, though the timing is often standardized for convenience. Also, for mycophenolate, AUC monitoring is ideal but logistically challenging-many centers now use the 2-hour post-dose level as a practical surrogate with good correlation. Precision matters.

Natashia Luu December 3, 2025 AT 08:15

It's alarming how many clinicians still rely on outdated immunoassays. This isn't just negligence-it's malpractice waiting to happen. Patients deserve better. If your hospital can't afford LC-MS/MS, they shouldn't be doing transplant monitoring at all. The cost of a single rejection episode dwarfs the cost of proper testing.

akhilesh jha December 4, 2025 AT 20:12

Interesting. In India, we rarely do TDM for tacrolimus due to cost. We use fixed doses and hope for the best. Some patients do fine. Others get kidney damage or reject. We don't have the luxury of choice. But I read this and wonder-how many lives could we save if we had even basic access to LC-MS/MS? Maybe someday.

Jeff Hicken December 6, 2025 AT 18:35

lol so now we're using viruses to monitor drugs? next they'll be reading our thoughts with a smartwatch. this whole thing is overengineered. just give me the pills and stop poking me.

Vineeta Puri December 6, 2025 AT 22:14

Thank you for this comprehensive overview. As a mentor to newly transplanted patients, I often emphasize that monitoring isn't about distrust in your body-it's about partnership with your medical team. The numbers aren't your enemy; they're your early warning system. I've seen patients who skipped labs for "feeling fine" end up in ICU. Your health is worth the inconvenience. Stay consistent. You're not alone in this journey.