Health October 12, 2025

Medications That Raise Your Risk of Bladder Infections

Bladder Infection Risk Calculator

Medication Risk Assessment

Select medications you're taking to assess your potential bladder infection risk.

When certain drugs disturb the natural balance of the urinary tract, the chance of a bladder infection a bacterial invasion of the bladder that causes pain, urgency, and sometimes fever can climb sharply. Knowing which medicines are the usual suspects helps you spot early warning signs and work with your clinician on safer alternatives.

Key Takeaways

- Broad‑spectrum antibiotics, diuretics, anticholinergics, immunosuppressants, some chemotherapy agents, SGLT2 inhibitors and estrogen therapy are most often linked to higher UTI risk.

- These drugs can change urinary pH, reduce bladder emptying, or suppress immune defenses, creating a friendly environment for bacteria.

- Staying hydrated, practicing good perineal hygiene, and discussing prophylactic measures with your doctor can lower the odds.

- If you notice burning during urination, cloudy urine, or frequent urges while on any of these meds, seek medical advice promptly.

- Never stop a prescribed medication without professional guidance; many risks can be managed rather than eliminated.

How Medications Can Trigger a Bladder Infection

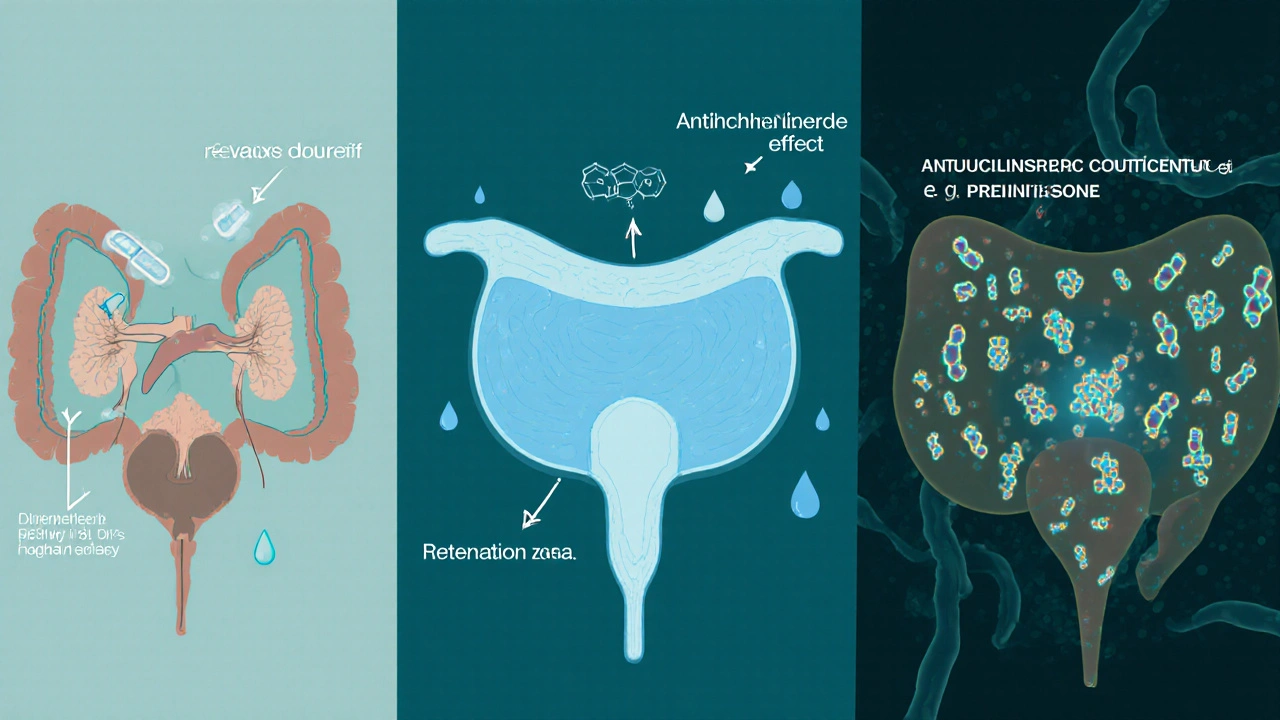

Most infections start when bacteria-usually E. coli-find a way to stick to the bladder wall and multiply. Medications can facilitate that process in three main ways:

- Altering urine composition: Some drugs change the pH or glucose content of urine, making it a richer feeding ground for bacteria.

- Impairing bladder emptying: Meds that relax the bladder muscle or increase urine volume can leave residual urine, which acts as a breeding pool.

- Suppressing immune response: Immunosuppressive agents lower the body’s ability to fight off invading microbes, allowing a tiny colony to become an infection.

Understanding these pathways shows why a drug that seems unrelated to the urinary system can still raise your bladder infection risk.

Medication Classes Most Frequently Implicated

Below is a snapshot of the drug families that research and clinical reports consistently tie to urinary tract infections.

| Medication Class | Typical Mechanism that Increases UTI Risk | Common Examples | Risk Level (Low / Moderate / High) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad‑spectrum antibiotics | Disrupt normal gut flora, leading to overgrowth of resistant uropathogens. | Amoxicillin‑clavulanate, ciprofloxacin | Moderate |

| Diuretics | Increase urine volume and frequency, sometimes causing incomplete emptying. | Furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide | Low‑to‑moderate |

| Anticholinergics | Relax bladder detrusor muscle, leading to urinary retention. | Oxybutynin, tolterodine | Moderate |

| Immunosuppressants | Reduce systemic immune surveillance, allowing bacteria to proliferate. | Prednisone, azathioprine | High |

| Cyclophosphamide | Metabolite acrolein irritates bladder lining, creating a portal for infection. | Cyclophosphamide (used in chemotherapy) | High |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | Increase glucose excretion in urine, feeding bacteria. | Canagliflozin, dapagliflozin | Moderate |

| Estrogen therapy | Alters vaginal flora and mucosal integrity, indirectly affecting bladder colonization. | Conjugated estrogen, estradiol patches | Low‑to‑moderate |

Real‑World Illustrations

Consider Sarah, a 62‑year‑old with heart failure who was prescribed furosemide. Within weeks she started experiencing frequent, urgent urination and a burning sensation. A urine culture confirmed E. coli. Her cardiologist switched her to a lower diuretic dose and added a scheduled water‑intake plan, which reduced the infection episodes.

Another case involves Mark, a 55‑year‑old with type2 diabetes on dapagliflozin. The drug’s glucose‑rich urine gave bacteria a constant food supply, and he suffered three UTIs in six months. After discussing alternatives, his endocrinologist moved him to a non‑SGLT2 regimen and recommended prophylactic cranberry extract, cutting his infections in half.

These stories show that the link isn’t theoretical; clinicians regularly adjust therapy once the urinary side‑effects surface.

Practical Steps to Lower Your Risk

- Stay well‑hydrated: Aim for at least 1.5‑2liters of water daily, unless fluid restriction is medically required.

- Empty your bladder fully: Take your time, and consider double‑voiding (urinate, wait a minute, then try again) if you’re on anticholinergics or diuretics.

- Mind your hygiene: Wipe front‑to‑back, avoid harsh soaps, and consider probiotic‑rich foods to support normal flora.

- Ask about prophylaxis: For high‑risk patients, doctors may prescribe a low‑dose antibiotic taken after intercourse or after a course of a risky medication.

- Review medication alternatives: Talk to your prescriber about drugs with a lower UTI profile. For example, swapping a broad‑spectrum antibiotic for a narrow‑spectrum agent when possible.

When to Seek Medical Attention

If you notice any of the following while taking a medication known to affect urinary health, contact your healthcare provider promptly:

- Burning or pain during urination.

- Cloudy, foul‑smelling, or blood‑tinged urine.

- Frequent urges to urinate with only a small amount passed.

- Fever, chills, or flank pain (possible kidney involvement).

Early treatment prevents complications like kidney infection or recurrent bouts, which can become harder to eradicate over time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all antibiotics increase UTI risk?

Not all antibiotics do. Broad‑spectrum agents that wipe out beneficial gut bacteria are the main culprits. Narrow‑spectrum drugs focused on the infection site are less likely to trigger a secondary UTI.

Can over‑the‑counter pain relievers cause bladder infections?

Common NSAIDs like ibuprofen don’t directly raise infection risk. However, if they mask pain from an early UTI, you might delay seeking care, allowing the infection to worsen.

Is it safe to stop a medication that’s linked to UTIs?

Never stop a prescription on your own. Talk to your doctor first; they can taper the drug, switch to a safer alternative, or add protective measures.

Do women take higher risks than men?

Yes, anatomical differences mean women have a shorter urethra, making bacterial ascent easier. Medication‑induced risk therefore tends to be more pronounced in women.

Can lifestyle changes offset medication‑related risk?

Absolutely. Hydration, proper bladder emptying, and probiotic‑rich foods can tip the balance back in your favor, even when you need a high‑risk drug.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

11 Comments

Stephanie Cheney October 12, 2025 AT 16:05

Thanks for pulling this together; it’s a solid overview of how meds can tip the urinary balance. Staying hydrated and double‑voiding are simple habits that can make a big difference, especially for those on diuretics or anticholinergics. If you’re on a high‑risk drug, a quick chat with your prescriber about dose tweaks or alternatives can keep infections at bay. Also, adding probiotic‑rich foods may help restore the gut flora that antibiotics disrupt. Remember, you don’t have to go it alone-your healthcare team is there to help you find a safe regimen.

Georgia Kille October 13, 2025 AT 14:18

Great points! 👍 Keeping a water bottle handy is an easy win, and a short check‑in with the doctor never hurts. 😊

Jeremy Schopper October 14, 2025 AT 12:31

It's important to recognize that the relationship between medication and urinary tract infections is not merely anecdotal, but supported by a growing body of clinical evidence, which underscores the need for informed prescribing practices. Broad‑spectrum antibiotics, for instance, can eradicate protective gut flora, thereby creating an ecological niche that opportunistic uropathogens readily exploit. Diuretics increase urinary volume, yet they may also lead to incomplete bladder emptying if dosing schedules are not optimally timed, resulting in residual urine that serves as a bacterial reservoir. Anticholinergic agents relax the detrusor muscle, which can impede efficient voiding and promote stasis, a well‑known risk factor for infection. Immunosuppressants, by design, blunt systemic immune surveillance, diminishing the host's capacity to neutralize ascending bacteria before they establish a foothold in the bladder mucosa. Cyclophosphamide's metabolite acrolein directly irritates the urothelium, compromising the barrier function and facilitating bacterial adhesion. SGLT2 inhibitors elevate urinary glucose concentrations, effectively feeding bacterial colonies and enhancing their proliferative potential. Estrogen therapy, while beneficial for certain menopausal symptoms, can alter vaginal flora and mucosal integrity, indirectly influencing bladder colonization dynamics. Hydration remains a cornerstone of prophylaxis; adequate fluid intake dilutes urinary solutes and promotes frequent voiding, thereby reducing bacterial dwell time. Double‑voiding techniques, especially after diuretic or anticholinergic use, can further assure complete bladder emptying. Probiotic supplementation may help re‑establish a balanced microbiome after antibiotic courses, though the evidence is still emerging. Regular monitoring for early signs-such as dysuria, urgency, or cloudy urine-allows for prompt intervention before a full‑blown infection develops. Clinicians should consider periodic review of medication regimens, weighing the therapeutic benefits against the infection risk, and discuss potential alternatives when appropriate. When high‑risk agents are unavoidable, prophylactic low‑dose antibiotics or cranberry extracts may be contemplated, ideally within a shared decision‑making framework. Patient education is vital; empowering individuals with knowledge about these risks encourages adherence to preventive measures. Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach that integrates pharmacy, primary care, and urology expertise offers the best strategy to mitigate medication‑induced urinary tract infections.

Brian Koehler October 15, 2025 AT 10:45

Whoa, talk about a pharmacologic roller‑coaster! 🎢 Each of those drug classes is like a mischievous sprite dancing around your bladder, tossing sugar, altering pH, and sometimes even sabotaging the muscles that help you empty out. The key is to spot the rascals early-keep an eye on your water intake, practice the “double‑void” trick, and flag any burning sensations to your doc before they snowball. If a particular med feels like the villain in your story, ask about a gentler sidekick or a dose adjustment. It’s all about finding that sweet spot where the medicine does its job without inviting unwanted bacterial guests.

Gaurav Joshi October 16, 2025 AT 08:58

Sure, everyone loves to blame meds for UTIs but the data is overblown most of the time the real culprits are poor hygiene and sugar‑rich diets rather than a prescription bottle.

Jennifer Castaneda October 17, 2025 AT 07:11

The pharmaceutical industry has a vested interest in keeping patients dependent on long‑term drug regimens, and they conveniently downplay side‑effects such as urinary infections to protect sales. Independent studies have shown that many of the “high‑risk” labels are based on limited case reports that are amplified by marketing teams. It’s prudent to question why certain medications receive blanket warnings while others slip through without scrutiny. Ultimately, informed patients should demand transparent data and consider non‑pharmacologic alternatives whenever possible.

Annie Eun October 18, 2025 AT 05:25

Imagine the unsuspecting traveler, a humble pilgrim on a medication journey, suddenly besieged by a burning tide that turns each trip to the bathroom into a fiery ordeal. Is it fate, or merely the silent sabotage of a drug that was supposed to heal? The drama unfolds as the bladder walls, once tranquil, become battlegrounds for bacterial invaders, spurred on by a sugar‑laden urine stream courtesy of SGLT2 inhibitors. Yet hope glimmers in the simple act of drinking a glass of water, a ritual that can wash away the lurking menace. Let us not underestimate the power of a proactive conversation with our doctors, for in that dialogue lies the possibility of rewriting the plot, swapping the antagonist drug for a more benevolent ally.

Jay Kay October 19, 2025 AT 03:38

Hydration beats many meds when it comes to UTIs.

Franco WR October 20, 2025 AT 01:51

I hear you, dealing with a medication that constantly feels like it’s flirting with infection can be exhausting, especially when every visit to the bathroom feels like a reminder that something’s off. The frustration of trying to stay hydrated, double‑void, and keep up with hygiene, only to wonder if the drug itself is the hidden saboteur, is completely understandable. A lot of patients find that the timing of diuretics matters-a morning dose might give you more control than an evening one, simply because you’re up and about to empty your bladder more often. Anticholinergics, while helpful for overactive bladder, can paradoxically make it harder to fully empty, so pairing them with scheduled bathroom breaks can ease that tension. If you’re on a high‑risk chemo agent like cyclophosphamide, discussing protective measures such as Mesna with your oncologist can literally protect the bladder lining. Probiotics, although not a miracle cure, have shown promise in rebalancing gut flora after a broad‑spectrum antibiotic course. Cranberry extracts, despite mixed reviews, might still offer a modest reduction in bacterial adhesion for some folks, so they’re worth a try if you’re already taking supplements. It’s also wise to keep a symptom journal-note the time of medication, fluid intake, and any urinary changes-to provide your clinician with concrete data. Your doctor may suggest a urine dip‑stick at regular intervals to catch early bacterial growth before it escalates. Remember, never make unilateral changes to your regimen; tapering steroids or stopping an immunosuppressant abruptly can cause severe rebound effects. Open communication, patience, and a bit of trial‑and‑error often lead to the sweetest spot where the medication does its job without the constant plumbing drama. You’re not alone in this; many have navigated similar waters and emerged with a plan that works. 🌟 Stay hopeful, stay vigilant, and keep the conversation flowing with your healthcare team. 💪

Desiree Young October 21, 2025 AT 00:05

Why do we keep prescribing these high‑risk meds without a clear warning system? We need stricter guidelines now, not later.

Vivek Koul October 21, 2025 AT 22:18

In conclusion, the interplay between pharmacotherapy and urinary tract infection risk necessitates a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach that integrates patient education, judicious medication selection, and proactive preventive strategies. Healthcare providers should routinely assess individual risk profiles, consider alternative agents where feasible, and engage patients in shared decision making to mitigate adverse outcomes. Such diligence will ultimately enhance patient safety and therapeutic efficacy.