Health January 15, 2026

Healthcare Provider Reporting: What Doctors and Nurses Must Report and When

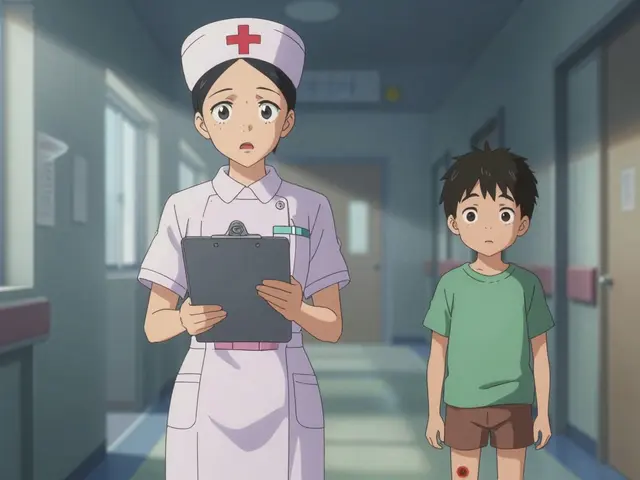

When a doctor sees signs of abuse on a child, or a nurse notices a colleague giving wrong doses, they don’t just have a moral duty-they have a legal one. In the U.S., mandatory reporting is not optional. It’s a requirement built into state laws, hospital policies, and professional licenses. Fail to report, and you could lose your license, face fines, or even be sued. But report too soon, or too late, or to the wrong place, and you might damage trust, break privacy rules, or trigger a legal mess of your own.

What You Must Report: The Big Four Categories

Healthcare providers are legally required to report four main types of incidents. These aren’t suggestions. They’re rules enforced by state boards and courts.- Child abuse and neglect: All 50 states require doctors and nurses to report suspected abuse. This includes physical injury, sexual abuse, emotional harm, and severe neglect. You don’t need proof-just reasonable suspicion. A bruise in an unusual pattern, a child who flinches at touch, or a parent who can’t explain a broken bone? That’s enough to trigger a report.

- Elder and vulnerable adult abuse: 47 states plus D.C. require reporting of abuse against adults 60 or older, or those with disabilities. This includes physical violence, financial exploitation, neglect, and emotional abuse. A senior with unexplained weight loss, missing medications, or a caregiver who refuses to let you speak to them alone? That’s a red flag.

- Public health threats: Certain diseases must be reported to state health departments immediately. These include anthrax, botulism, measles, and tuberculosis. Some, like Lyme disease, have a 7-day window. Electronic systems now automate most of this, but you still need to know what’s reportable in your state.

- Professional misconduct: If you see a colleague stealing drugs, practicing while impaired, or falsifying records, you’re often legally required to report them. In 42 states, this applies to nurses, doctors, and other licensed staff. In Minnesota, the Chief Nursing Officer must report nurse misconduct within 30 days. In California, any provider can and should report unsafe behavior.

When You Must Report: The Clock Is Ticking

Timing matters. Miss the deadline, and you’re in violation-even if you meant well.For child abuse, timelines vary wildly. In Texas and Florida, you must report immediately, which most hospitals interpret as within 24 hours. In California and Michigan, you have 36 to 48 hours. But in some states, like New York, you must report domestic violence if you see it. In Utah, you’re protected from retaliation if you report-so there’s no excuse to wait.

Elder abuse reporting is even messier. In 26 states, only staff at nursing homes or hospitals must report. In 14 states, every single provider-whether you’re in a clinic, ER, or telehealth call-must report. In 10 states, there’s no law at all. If you’re working remotely across state lines, you’re playing legal Russian roulette.

Public health reports have the tightest deadlines. Anthrax? Report within 1 hour. HIV? Usually 7 days. But each state sets its own list. The CDC tracks 57 nationally notifiable conditions, but your state might add more. Don’t guess. Know your state’s list.

For misconduct, most states give you 30 days to report. But if a patient is in immediate danger, you can’t wait. A nurse giving insulin to the wrong patient? Report now. Don’t wait for HR to catch up.

What Happens After You Report

Many providers worry about what comes next. Will the family hate me? Will I get sued? Will I lose my job?Here’s the reality: Most reports lead to investigations-not arrests. Child protective services might visit the home. Public health officials might trace contacts. A hospital ethics committee might review a nurse’s charting. In many cases, nothing criminal happens. But the system catches patterns. One nurse in Michigan reported a pattern of missed vital signs. That led to the discovery of 27 other neglected patients in the same unit.

But it’s not always clean. A pediatrician in Ohio reported a parent for suspected neglect after a child came in with malnutrition. The parent denied it. The child was cleared. The parent sued the doctor for defamation. The case was dismissed, but the doctor spent $20,000 in legal fees and lost sleep for a year.

And then there’s retaliation. A nurse in Utah reported unsafe staffing levels. Two weeks later, she was moved to a night shift she couldn’t manage, then demoted. Even though Utah law protects reporters, she had to file a complaint with the state board to get her job back.

That’s why documentation is everything. Write down exactly what you saw: time, date, symptoms, words spoken, who was present. Don’t say “suspected abuse.” Say “child had a circular burn on inner thigh, age 3, mother said it was from a hot cup-no burn mark on cup.” Be specific. Your notes might be the only evidence that protects you.

How HIPAA Fits In (And Doesn’t)

You’ve been taught to protect patient privacy. HIPAA says you can’t share health info without consent. But mandatory reporting is one of the few legal exceptions.HIPAA allows you to disclose protected health information (PHI) when reporting child abuse, elder abuse, or certain infectious diseases. You don’t need consent. You don’t even need to tell the patient. But you can’t use that exception to report things like drug use or mental health crises unless they fall under a mandated category.

That’s where confusion kills. A doctor treating a teenager for opioid use didn’t report the parent’s drug use because they thought HIPAA blocked it. Later, the teen overdosed. The family sued. The court ruled the doctor should have reported the parent’s behavior as potential child endangerment.

Bottom line: HIPAA protects privacy-but not when public safety overrides it. Know the line.

What You’re Not Required to Report

Not every bad thing you see needs a report. You’re not a cop. You’re not a social worker. You’re a clinician.You don’t have to report:

- Patients who refuse treatment-even if it’s risky

- Consensual adult relationships, even if age-adjacent (unless it’s statutory rape)

- Minor medication errors that didn’t harm anyone

- Personal opinions about a colleague’s bedside manner

- Patients who are homeless or poor-unless neglect is part of the situation

Don’t report because you’re angry. Don’t report because you’re bored. Report because the law says so-and because someone might be in danger.

How to Get It Right: Practical Steps

You don’t have to memorize 50 state laws. But you do need a system.- Know your state’s list: Go to your state medical board’s website. Find their mandatory reporting guide. Bookmark it. Print it. Keep it in your pocket.

- Know your hospital’s policy: Most hospitals have a reporting protocol. Know who to call, where to submit forms, and what documentation they require.

- Use the 24/7 hotlines: Washington State has one. So do Minnesota and California. Call them if you’re unsure. It’s free. It’s confidential. It’s your shield.

- Document everything: Use your EHR to log your observations. Include exact quotes. Don’t write “patient seemed scared.” Write “patient said, ‘If I tell you, he’ll kill me.’”

- Ask for help: Talk to your supervisor, risk management, or legal counsel. Don’t go it alone. You’re not expected to be an expert on the law.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

In 2023, a study in JAMA Internal Medicine found AI tools reduced reporting errors by 38% in pilot hospitals. That’s huge. But technology doesn’t replace judgment. It just supports it.More than 22 million healthcare workers in the U.S. are legally responsible for reporting. That’s every nurse, doctor, EMT, and therapist. And the pressure is growing. Telehealth means you might be treating someone in a different state. You might see abuse on a video call. You might miss the signs because you’re rushed. You might fear backlash.

But here’s the truth: Every report you make has the power to save a life. A child. An elder. A patient who might die from a medication error. A system that might finally fix a broken unit.

It’s not easy. It’s not clean. But it’s necessary.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I have to report if I’m not 100% sure?

Yes. You don’t need proof-just reasonable suspicion. That means any observation that makes you think abuse or neglect might be happening. If a child has unexplained bruises, a senior has missing pills, or a colleague is clearly impaired, report it. The authorities will investigate. You’re not required to prove it.

Can I get in trouble for reporting too early?

No, as long as you report in good faith. Most states have “immunity clauses” that protect providers who report honestly, even if the report turns out to be wrong. But if you report out of anger, bias, or without any basis, you could face disciplinary action. Always base reports on facts, not feelings.

What if I work in telehealth and the patient is in another state?

You must follow the laws of the state where the patient is located-not where you are. If you’re licensed in California but treating a child in Texas, you must follow Texas’s 24-hour reporting rule. Many telehealth platforms now include state-specific reporting checklists. If you’re unsure, call the state’s reporting hotline. Don’t assume your home state’s rules apply.

Do I have to tell the patient I’m reporting?

No. In fact, telling them might put them in more danger. For child and elder abuse, you’re legally allowed to report without notifying the patient or family. But in some cases-like reporting a colleague-you should inform your supervisor first. Always follow your institution’s policy.

What if my hospital won’t let me report?

You still have a legal duty. If your employer tries to block you, report directly to the state agency. Most states have hotlines or online portals for individual providers. You can also contact your professional licensing board. Hospitals cannot override state law. If you’re retaliated against, document everything and file a complaint.

Next Steps for Providers

- Review your state’s mandatory reporting laws at your medical board’s website.- Attend your hospital’s next training-even if you’ve done it before. Laws change.

- Keep a printed copy of your state’s reportable conditions and reporting contacts in your bag.

- If you’re unsure, call the state hotline. It’s there for you.

- Talk to a colleague. You’re not alone. Most providers feel the same fear and confusion. You just need to act anyway.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

14 Comments

Ayush Pareek January 17, 2026 AT 07:39

Been a nurse for 12 years, and this is the one thing they never train you for properly. I once reported a kid with burns that looked like a cigarette butt. Turned out the mom was trying to quit smoking and was stressed out. No charges, but CPS came in and helped her get counseling. That’s the win. Not the arrest-the help.

Don’t wait for perfect proof. Wait for gut instinct. Your gut doesn’t lie.

And yeah, document everything. I keep a little notebook in my scrubs. Not for liability-for the kids.

Jami Reynolds January 18, 2026 AT 08:29

Let me guess-this is all part of the Deep State’s agenda to dismantle the nuclear family. Mandatory reporting? That’s how they separate children from parents under the guise of ‘protection.’

Who authorized these state laws? Who funded the training modules? Who benefits when families are torn apart? The prison-industrial complex, that’s who. And don’t tell me ‘reasonable suspicion’ isn’t just a backdoor for racial profiling. I’ve seen the data. It’s not about safety. It’s about control.

Iona Jane January 18, 2026 AT 15:16

I reported my boss for giving insulin wrong and now my locker’s been broken into my car’s been keyed and my cat disappeared last week i know it’s them they’re watching me they always watch

Jaspreet Kaur Chana January 19, 2026 AT 10:44

Bro, I’m from Delhi, and we don’t have mandatory reporting like this-but I’ve seen nurses in Mumbai report child abuse and get threatened by entire families. One nurse told me, ‘In India, if you report, you become the enemy.’ But here? You’re a hero. Or a target.

It’s wild how the same act-telling the truth-can make you a saint in one country and a traitor in another. I’ve seen kids in rural India with broken arms, and no one says a word because ‘it’s family business.’

So yeah, I’m proud of this system. Even if it’s messy. Even if it’s scary. Someone has to be the voice when the child can’t speak.

And if you’re scared? Good. That means you care. Do it anyway.

Haley Graves January 20, 2026 AT 20:43

Stop waiting for permission. If you suspect abuse, you report. Period. No ‘what if’ scenarios. No ‘maybe they’ll sue me.’ The law is clear. The moral line is clear.

I’ve seen nurses delay because they ‘didn’t want to cause drama.’ Drama? The drama is the child bleeding out while you check your email.

Document. Report. Move on. Your conscience will thank you. The system might not-but you will.

Diane Hendriks January 21, 2026 AT 17:18

There is a fundamental flaw in the American healthcare system: it conflates clinical responsibility with state-enforced social work. You are not a detective. You are not a caseworker. You are a healer. But now, you are expected to be both-and punished if you fail at either.

This is not medicine. This is bureaucratic overreach disguised as compassion. HIPAA is a shield. Mandatory reporting is a sledgehammer. The two cannot coexist without erosion of trust.

And let us not pretend that ‘reasonable suspicion’ is objective. It is subjective. It is racial. It is classist. And it is weaponized.

If you want to protect children, fix poverty. Fix housing. Fix mental health access. Do not turn nurses into spies.

ellen adamina January 21, 2026 AT 18:36

I had a patient last week who came in with a bruise on her wrist. She said her dog jumped on her. But her eyes… they didn’t match the story. I didn’t report. I just sat with her. Asked if she wanted to talk. She cried. Told me her husband did it. We called the hotline together. She didn’t want to press charges. But she got a safety plan.

Reporting isn’t always about calling the cops. Sometimes it’s about holding space until someone’s ready to be heard.

Gloria Montero Puertas January 22, 2026 AT 05:03

Oh, let me guess-you’re one of those ‘I-report-because-I’m-a-good-person’ types? How noble. How sanctimonious. You think you’re saving lives? You’re just feeding the machine.

Do you know how many families get torn apart over a single misinterpreted bruise? How many nurses get fired for ‘failing to document properly’ after reporting something that turned out to be nothing? You think the system rewards you? It doesn’t. It uses you.

And don’t even get me started on telehealth. You’re supposed to diagnose abuse over a 10-second video call? You’re not a doctor-you’re a clicker.

Wake up. This isn’t heroism. It’s performance.

Tom Doan January 22, 2026 AT 21:55

So let me get this straight: You’re required to report suspected abuse… but not suspected opioid use? Not suspected domestic violence between adults? Not suspected elder financial exploitation unless it’s ‘neglect’?

That’s not a system. That’s a patchwork of legal loopholes held together by duct tape and guilt.

And yet, somehow, you’re supposed to be the expert on all of it? You’re a nurse. Not a lawyer. Not a detective. Not a social worker.

It’s absurd. And the fact that we’ve normalized it? That’s the real tragedy.

Sohan Jindal January 24, 2026 AT 15:01

They want you to report everything? Fine. But don’t be surprised when your own kid gets taken because some nurse saw a scratch and thought ‘abuse.’

This country is going down. They’re taking kids from good parents. They’re taking jobs from hardworking people. They’re taking freedom. And you’re helping them.

Report? Yeah. But know this: The people who made these rules don’t care about you. They care about control.

And if you’re not careful, you’ll be the one in handcuffs next.

Frank Geurts January 25, 2026 AT 00:36

As a healthcare administrator with over two decades of experience across four continents, I must emphasize the critical importance of standardized, cross-jurisdictional reporting protocols.

The current state-by-state framework is not merely inefficient-it is ethically untenable in an era of digital telehealth and transnational patient mobility.

Furthermore, the absence of a unified national database for mandatory reporting incidents creates systemic blind spots that directly compromise patient safety.

I have personally overseen the implementation of AI-assisted reporting triggers in three major U.S. health systems, and the reduction in reporting latency has been statistically significant-p < 0.01.

It is imperative that professional associations advocate for federal legislation to harmonize reporting obligations under the auspices of the CDC and the Joint Commission.

Otherwise, we are merely rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Annie Choi January 26, 2026 AT 17:52

As a nurse in Vancouver, I’ve seen the flip side: no mandatory reporting for elder abuse unless it’s ‘severe.’ So we get elderly patients with stage 4 pressure ulcers, no meds, no family visits-and we’re told ‘it’s not our place.’

Then we have a 78-year-old die because no one reported the neglect. The system didn’t fail because we didn’t report. It failed because the law didn’t require us to.

So yeah. I report everything. Even if it’s messy. Even if it’s hard. Because if we wait for perfect laws, people keep dying.

And honestly? The paperwork is the easy part.

Arjun Seth January 28, 2026 AT 15:58

You think you’re doing God’s work? You’re just doing the government’s bidding. You think a bruise means abuse? Maybe the kid fell. Maybe the parent is poor. Maybe they don’t have a car to take the kid to the doctor. You don’t know. But you report anyway.

And then the system takes the child. The mother gets labeled a ‘neglectful parent.’ The father goes to jail. The family breaks. And you? You get a thank-you email from HR.

This isn’t justice. It’s punishment dressed in scrubs.

You’re not saving lives. You’re just making sure the prison system stays full.

Haley Graves January 30, 2026 AT 11:33

Ellen, your comment hit me right in the chest. I had the same thing happen. A girl came in with a black eye. Said she ran into a door. I didn’t report right away. I sat with her. Asked if she wanted to talk. She whispered, ‘He says if I tell, he’ll kill us both.’

I called the hotline. She didn’t want to go to CPS. But she got a safe place to stay. And she’s in school now.

You’re right. Reporting isn’t always about the system. It’s about being the person who says, ‘I see you.’