Health October 3, 2025

Sneezing and Your Sense of Smell: Understanding the Connection

Sneezing & Smell Impact Calculator

Your Smell Impact Analysis

Ever wondered why a good sneeze can leave your world a little less fragrant for a few minutes? The short answer is that the nose does double duty - it clears unwanted stuff and carries the signals that let you enjoy aromas. This article unpacks how a simple reflex can temporarily mess with your ability to smell, what conditions make the problem linger, and what you can do to keep both sneeze and scent working smoothly.

Quick Take

- A sneeze forces a burst of air that can wash away odor‑detecting particles.

- Inflammation in the nasal cavity the hollow space inside the nose lined with mucus blocks the olfactory receptors.

- Allergies, colds, and sinus infections are the top culprits that link sneezing and temporary smell loss.

- Most smell disruptions clear up in days once inflammation subsides.

- If you lose your sense of smell for more than two weeks, see a doctor - it could signal a deeper issue.

How sneezing a rapid expulsion of air from the lungs through the nose and mouth to clear irritants Works

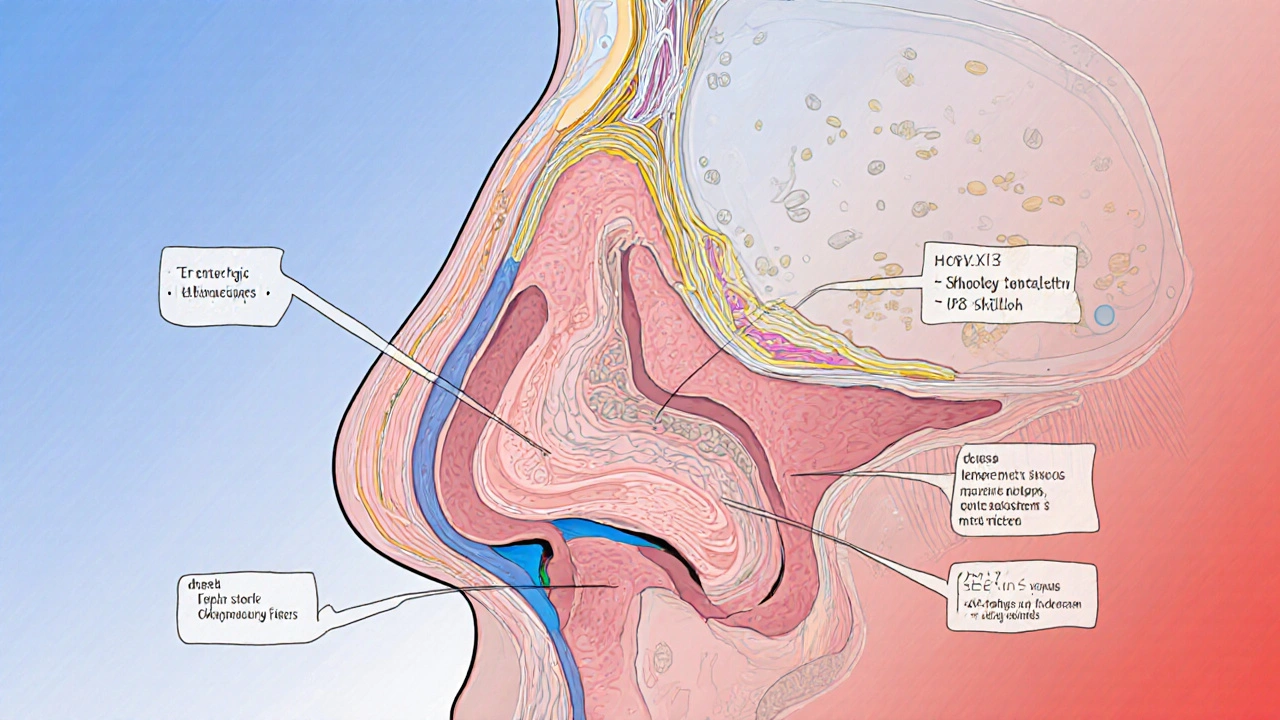

When a tiny particle or chemical irritates the lining of the nasal cavity the interior of the nose where mucus traps debris, sensory nerves fire a signal to the brainstem. The brain replies with a coordinated muscle contraction that closes the throat, raises the soft palate, and builds pressure in the lungs. The result is a powerful jet of air that shoots out of the nose, carrying the offending particles away.

This reflex protects the respiratory system, but the same burst can also disturb the delicate film of mucus that sits over the olfactory receptors - the tiny protein sensors that bind odor molecules.

Basics of the sense of smell the ability to detect and interpret chemical compounds in the air

The olfactory system starts at the upper part of the nasal cavity, where the olfactory nerve a bundle of nerve fibers that carry smell signals to the brain sits just above the nasal septum. When odor molecules dissolve in the mucus layer, they bind to receptors on the olfactory nerve cells. This triggers electrical impulses that travel to the olfactory bulb and then to brain regions that recognize and give meaning to smells.

Any factor that thins, blocks, or inflames that mucus layer can dampen the signal, making the world seem muted.

Why a Sneeze Can Dim Your Aroma Radar

During a sneeze, the rapid airflow does two things that affect smell:

- Physical displacement - the gust can blow away odor‑binding molecules before they have a chance to interact with receptors.

- Temporary swelling - the nerves that trigger the sneeze release histamine and other inflammatory mediators. These chemicals cause the lining of the nasal cavity to swell, narrowing the passage for air (and for odor molecules) and compressing the olfactory epithelium.

Both effects are short‑lived, which is why most people notice a brief “blank” after a big sneeze. However, repeated sneezing from chronic conditions can keep the nasal tissues inflamed, leading to a longer‑term reduction in smell acuity.

Common Triggers That Couple Sneezing and Smell Loss

Not every sneeze comes with a smell dip, but certain health issues make the link much stronger. Below is a snapshot of the usual suspects.

| Condition | Typical Sneezing Frequency | Impact on Smell | Recovery Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allergic rhinitis | Frequent, often in bursts | Temporary dulled smell; may become chronic if exposure continues | Days to weeks after allergen removal |

| Common cold | Intermittent, worsens with congestion | Noticeable loss while mucus is thick | 7‑10 days on average |

| COVID‑19 (upper‑respiratory phase) | Occasional, may accompany dry cough | Sudden, sometimes profound loss that can persist beyond sneezing | Weeks to months, depending on severity |

| Sinus infection | Often accompanied by pressure | Reduced smell due to blocked olfactory cleft | 2‑4 weeks with treatment |

| Nasal polyps | May trigger sneezing when irritated | Chronic reduction; often requires surgical removal | Variable; can improve after intervention |

Notice how the table groups each condition by how it inflames the nasal lining and whether the smell loss is fleeting or more persistent.

When to Seek Professional Help

Most episodes resolve on their own, but watch for these red flags:

- Loss of smell lasting longer than two weeks without improvement.

- Severe facial pain or swelling that doesn't respond to over‑the‑counter decongestants.

- Repeated sneezing bouts that interfere with daily life.

- Any sudden loss of smell accompanied by fever, which could signal COVID‑19 or a serious infection.

Your GP may refer you to an ENT specialist. They might perform a nasal endoscopy to look for polyps, conduct allergy testing, or order a CT scan of the sinuses if a deeper issue is suspected.

Practical Tips to Keep Both Sneezing and Smelling in Check

- Stay hydrated. Thin mucus is less likely to block receptors.

- Use saline nasal rinses. A gentle salt‑water spray clears irritants without harsh chemicals.

- Manage allergens. Keep windows closed during high pollen days, wash bedding weekly, and consider HEPA filters.

- Limit irritants. Smoke, strong fragrances, and spicy foods can trigger sneezes and swelling.

- Consider antihistamines. They reduce histamine release, limiting both sneeze frequency and nasal swelling. Choose non‑sedating options if you need to stay alert.

- Seek timely treatment. Early antibiotics for bacterial sinusitis or steroid sprays for chronic inflammation can prevent long‑term smell loss.

By keeping the nasal passage clear and reducing inflammation, you give your olfactory nerve the best chance to stay sharp, even after the next sneeze.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my sense of smell feel “foggy” after a sneeze?

The burst of air pushes away odor molecules and the histamine released during the sneeze causes the nasal lining to swell. Both actions reduce the amount of scent that reaches the olfactory receptors for a few minutes.

Can frequent sneezing cause permanent smell loss?

Frequent sneezing itself isn’t usually the problem; it’s the chronic inflammation behind it. Conditions like untreated allergies or persistent sinus infections can lead to long‑term damage to the olfactory epithelium if left unchecked.

Is it normal for COVID‑19 to cause sneezing?

Sneezing is less common than a dry cough for COVID‑19, but it can occur, especially early on. The virus often targets the olfactory nerve directly, leading to a sudden loss of smell that may or may not be accompanied by sneezing.

How long does it take for my smell to return after a cold?

Most people notice improvement as the congestion lifts, typically within a week. If the smell stays dulled after two weeks, a follow‑up with a doctor is advisable.

Are nasal sprays safe for protecting my sense of smell?

Saline sprays are safe for daily use. Steroid sprays can reduce inflammation but should be used under medical guidance, especially if you need them for more than a few weeks.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

18 Comments

kunal ember October 3, 2025 AT 20:19

When you sneeze, the burst of air does more than just clear the nasal passage; it also temporarily displaces the thin layer of mucus that holds odor molecules in place. This displacement means that for a few seconds the olfactory receptors are starved of scent cues, which is why the world feels a bit bland right after a sneeze. The sneeze reflex also triggers histamine release, causing the nasal lining to swell and narrow the pathways that odorants travel through. Even a single sneeze can reduce the volume of air reaching the olfactory epithelium, and repeated sneezing compounds this effect by keeping the tissue inflamed. In people with allergies, the baseline inflammation is already higher, so each sneeze adds to an already reduced sense of smell. A common cold adds mucus thickness, which further blocks odor molecules from diffusing to the receptors. Viral infections like COVID‑19 can directly damage the olfactory neurons, making the temporary loss more pronounced and sometimes longer‑lasting. Sinus infections create pressure and edema that physically obstruct the olfactory cleft, leading to a more persistent hyposmia. Nasal polyps act like physical barriers that not only cause sneezing but also trap scent particles away from the receptors. Saline rinses help by thinning mucus and flushing out irritants, thereby restoring the normal flow of odorants. Antihistamines can reduce swelling, but they should be used under medical guidance to avoid over‑drying the nasal passages. Staying well‑hydrated keeps mucus at an optimal consistency, which is crucial for both smelling and minimizing sneeze triggers. Environmental control, such as using HEPA filters and avoiding strong fragrances, reduces the frequency of sneezing episodes. If smell loss persists beyond two weeks, it may indicate lingering inflammation or nerve damage that warrants an ENT evaluation. Early treatment of bacterial sinusitis with antibiotics can prevent long‑term olfactory deficits. Monitoring your symptoms with a simple diary can help you identify patterns and discuss them accurately with your healthcare provider.

Kelly Aparecida Bhering da Silva October 7, 2025 AT 21:32

Don't be fooled – the mainstream media downplays how allergens are weaponized to keep us compliant. The truth about sneezing is hidden in plain sight.

Michelle Dela Merced October 11, 2025 AT 22:46

OMG, I swear my nose is a drama queen that throws a sneeze party every allergen season! 😂🌸

Alex Iosa October 15, 2025 AT 23:59

While speculation abounds, the scientific consensus indicates that sneezing-related inflammation is a physiological response, not a covert operation. It is advisable to focus on evidence‑based treatments rather than unfounded conspiracies.

melissa hird October 20, 2025 AT 01:12

Ah, the wonderfully over‑dramatic world of sneeze‑induced hyposmia – how delightfully predictable. One might suggest a paracetamol‑infused saline rinse, if only to add a dash of excitement to the otherwise mundane routine.

Mark Conner October 24, 2025 AT 02:26

Yo, if you keep letting those sneezes run wild you’re basically signing up for a permanent sniff‑loss. Shut it down with some antihistamines, ASAP.

Charu Gupta October 28, 2025 AT 02:39

Saline nasal rinses are scientifically proven to alleviate congestion and restore olfactory function. 😊 Please consider incorporating them into your daily regimen.

Abraham Gayah November 1, 2025 AT 03:52

Seriously, I’ve read every article on this and they’re all the same boring fluff. Can we get some real insight?

rajendra kanoujiya November 5, 2025 AT 05:06

Contrary to popular belief, reading fluff doesn’t make you any smarter about nasal physiology.

Caley Ross November 9, 2025 AT 06:19

I’ve noticed that staying hydrated helps my sneezes feel less harsh, which in turn keeps my sense of smell sharper.

Bobby Hartono November 13, 2025 AT 07:32

It's kind of amazing how much our daily habits affect something as subtle as smell. When I started using a humidifier at night, the mucus stayed thinner and I stopped losing my sense of smell after a sneeze. Also, cutting back on spicy foods reduced the frequency of those intense sneezing bouts. Keeping a small bottle of saline spray at my desk means I can give my nose a quick rinse after a sudden sneeze, which seems to reset the olfactory receptors. Finally, I’ve found that taking short walks outdoors, especially in areas with good air quality, helps clear any lingering irritants that might trigger a sneeze later on. Overall, a holistic approach really makes a difference.

George Frengos November 17, 2025 AT 08:46

Great practical tips, Bobby. Staying hydrated and using saline are indeed simple yet effective measures. Encouraging others to adopt these habits can help maintain olfactory health.

Jonathan S November 21, 2025 AT 09:59

Honestly, most people ignore the tiny details like room humidity and end up with chronic smell loss. That’s why it’s crucial to treat the nose like a garden that needs regular watering and weeding.

Charles Markley November 25, 2025 AT 11:12

The metaphor of a garden is apt, yet one must also consider the microbiome dynamics that influence mucosal immunity. Integrating probiotic nasal sprays could represent a next‑generation intervention, albeit with regulatory hurdles.

L Taylor November 29, 2025 AT 12:26

Interesting take on probiotics for nasal health, though more research is needed.

Matt Thomas December 3, 2025 AT 13:39

i cant beleve how many ppl ignore the basics like staying hydrated it s like u r missing out on easy fix

Nancy Chen December 7, 2025 AT 14:52

Some folks think the sneeze‑smell link is a secret plot, but the real intrigue lies in how airborne particles, like those from industrial emissions, can hijack our nasal receptors and turn a simple sneeze into a prolonged sensory blackout.

Jon Shematek December 11, 2025 AT 16:06

Let’s keep it positive – taking simple steps like hydration, saline rinses, and allergen control can empower anyone to protect their sense of smell and stay confident.