Health November 20, 2025

30-Month Stay: How Patent Litigation Delays Generic Drug Approval

When a brand-name drug company gets FDA approval, it doesn’t mean the drug will stay exclusive forever. But in the U.S., there’s a powerful legal tool that can block generics for years - even after the patent expires. It’s called the 30-month stay, and it’s not a bug in the system. It’s the system.

What Is the 30-Month Stay?

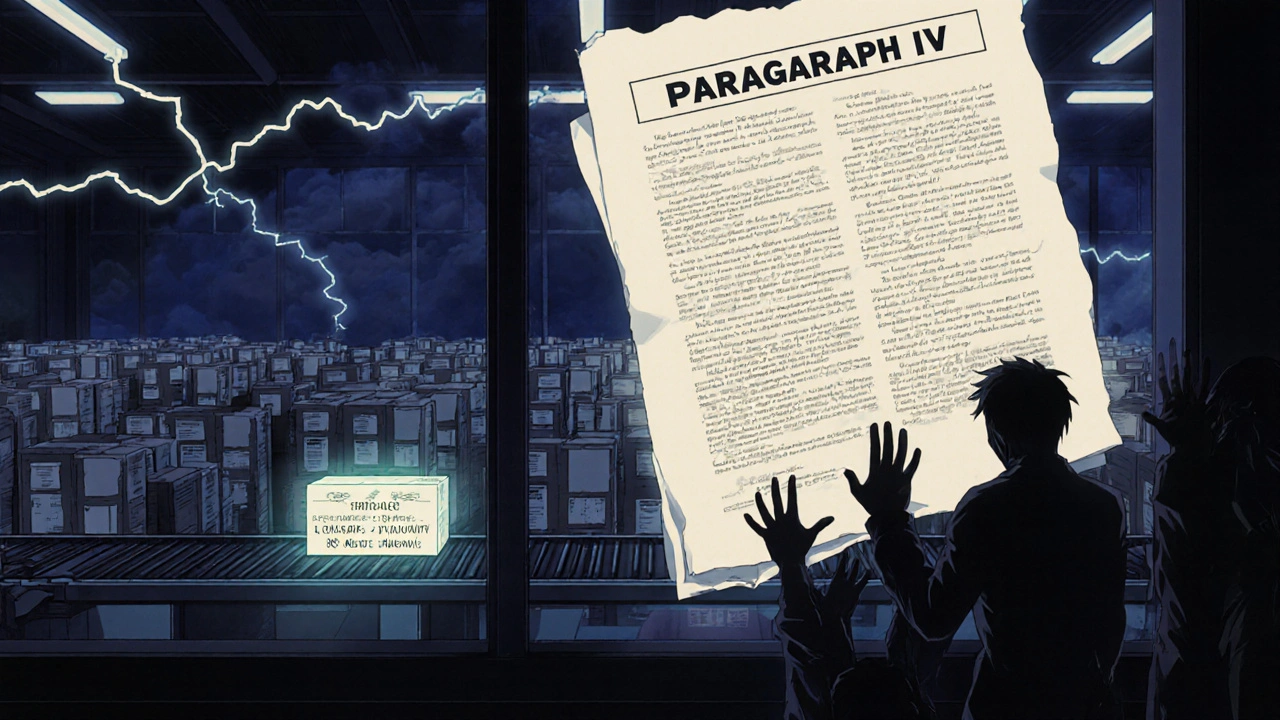

The 30-month stay is part of the Hatch-Waxman Act, passed in 1984. It was meant to balance two goals: letting generic drugs reach the market faster, while still protecting the innovation that made those drugs possible. Here’s how it works in practice.A generic drug maker files an application with the FDA to sell a cheaper version of a brand-name drug. But if they claim the brand’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed - known as a Paragraph IV certification - the brand company gets 45 days to sue for patent infringement. If they do, the FDA is legally blocked from approving the generic for up to 30 months. That’s the stay.

It doesn’t stop the FDA from reviewing the application. They can give a tentative approval during this time. But they can’t give the final green light. The clock only starts ticking after the brand company files suit. And if the lawsuit drags on past 30 months? The stay can extend - unless a court says otherwise.

Why Does This Matter?

The 30-month stay isn’t just paperwork. It’s a financial firewall. In 2022, the FDA received 1,046 generic drug applications. Nearly 80% of them were stuck in this legal limbo. That means thousands of patients couldn’t get cheaper versions of their meds - not because the drugs weren’t safe, but because lawyers were still arguing in court.Take a drug like Humira. When its main patent expired, the brand company filed dozens of secondary patents - on packaging, dosing methods, even how it’s administered. Each one triggered a new legal round. The result? Generic versions didn’t hit the market for over a decade after the original patent expired.

This isn’t rare. A 2019 Brookings study found that 67% of patents listed for top-selling drugs were filed after the original approval. These aren’t new inventions. They’re tweaks. But under Hatch-Waxman, they still trigger the 30-month stay.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

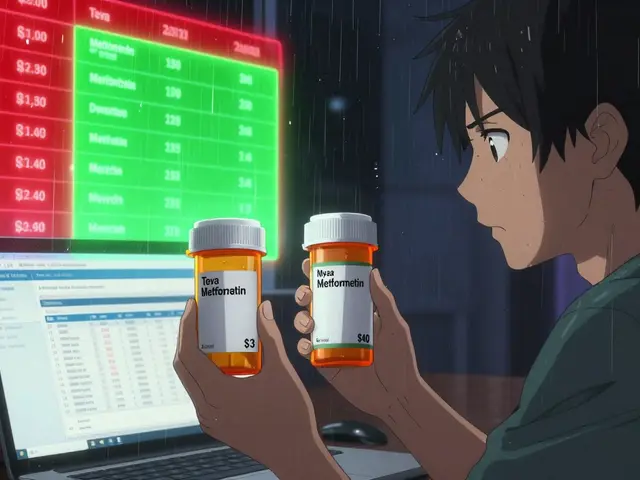

Brand-name companies say the stay is essential. Without it, they argue, no one would invest in new drugs. Scott Gottlieb, former FDA commissioner, says Hatch-Waxman has saved consumers $2.2 trillion since 1984 by enabling over 12,000 generic approvals. That’s true - but it ignores the cost of delay.The FTC estimates that patent litigation delays caused by the 30-month stay add $13.9 billion to U.S. drug costs every year. That’s not just corporate profit. It’s out-of-pocket costs for seniors, higher insurance premiums, and rationing by patients who can’t afford their meds.

On the other side, generic manufacturers spend $3-5 million per drug just on legal fees. A 2022 survey found 78% of them said preparing for litigation adds 6-9 months to their development timeline. That’s not just money. It’s time they could’ve spent testing, manufacturing, and getting drugs to patients.

The First-Mover Advantage

There’s one twist that makes this game even more intense: the 180-day exclusivity period for the first generic company to successfully challenge a patent. That’s a huge reward. If you’re first, you get to be the only generic on the market for half a year - no competition, full pricing power.That’s why companies race to file. In 2022, 72% of drugs faced multiple Paragraph IV challenges. But only one gets the prize. The rest? They’re left waiting - sometimes for years - while the first filer takes the market.

Ironically, having multiple challengers actually speeds things up. Drugs with more than one filer get approved 8.2 months faster on average. The competition forces quicker legal resolutions. But if one company settles with the brand, the others get stuck. That’s called a “pay-for-delay” deal - and it’s still common.

What’s Happening Now?

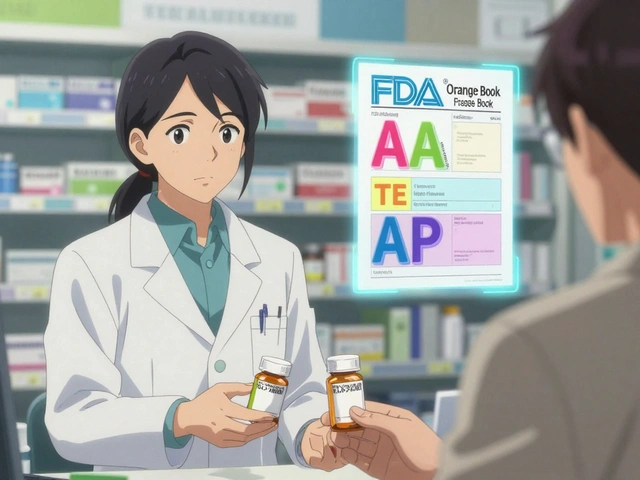

The system is under pressure. In 2023, Congress introduced the Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act. It proposes cutting the 30-month stay to 18 months and banning stays for secondary patents. The FTC is pushing for the same. They found that brand companies now list an average of 8.3 patents per drug - up from just 1.2 in 1995.The FDA is also stepping in. Their 2023 draft guidance wants more transparency in the Orange Book - the list of patents linked to brand drugs. Right now, companies can list patents that are vague, expired, or irrelevant. That creates unnecessary stays. If the FDA forces clearer listings, fewer frivolous lawsuits will trigger the 30-month block.

Meanwhile, the market is shifting. Biologics - complex drugs like insulin or cancer treatments - aren’t covered by Hatch-Waxman. They have their own 12-year exclusivity under the BPCIA. And biosimilars (the generic version of biologics) are growing fast. By 2028, they could make up 12% of the biologics market. That’s a new path to lower prices - one that doesn’t rely on the 30-month stay.

The Real Delay Isn’t the 30 Months

Here’s something most people miss: the 30-month stay rarely lasts the full 30 months. In fact, a 2021 study found that the median time between stay expiration and actual generic launch is 3.2 years. So what’s causing the real delay?It’s not the law. It’s commercial readiness. Companies don’t launch the moment they get approval. They wait for manufacturing capacity. They wait for distribution deals. They wait to see if their competitor will settle. Sometimes, they wait because the brand company is still fighting other patents.

One Teva regulatory specialist put it bluntly on a pharma forum: “The 30-month stay creates false security. The real delay is internal.”

What’s Next?

By 2028, over $78 billion in brand-name drugs will lose patent protection. If the 30-month stay stays unchanged, consumers will pay billions more than they should. If reforms pass - cutting the stay, banning secondary patents, increasing transparency - those savings could reach $195 billion.But change won’t come easy. The pharmaceutical industry spent over $100 million lobbying Congress in 2023. They argue that any change will hurt innovation. But the data tells a different story: the U.S. spends more on drugs than any other country - and still lags in generic access.

The 30-month stay was never meant to be a decades-long delay tactic. It was a temporary pause - a fair trade for innovation. Today, it’s become a permanent roadblock. And patients are the ones paying the toll.

What triggers the 30-month stay?

The 30-month stay is triggered when a generic drug manufacturer files a Paragraph IV certification challenging a patent listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, and the brand-name company files a patent infringement lawsuit within 45 days of being notified. The FDA then cannot approve the generic for up to 30 months, or until the court rules in favor of the generic, whichever comes first.

Does the 30-month stay always last 30 months?

No. The stay ends early if the court rules the patent is invalid or not infringed. It can also be extended if the litigation is unresolved and the FDA determines the delay is due to the generic applicant’s actions. But it rarely lasts the full 30 months - the average time between stay expiration and actual generic launch is 3.2 years, meaning other factors cause most delays.

Can a brand company trigger multiple 30-month stays?

No. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) limits brand companies to one 30-month stay per ANDA filer. They can’t file multiple lawsuits over different patents to extend the delay beyond one 30-month period for the same generic applicant.

What is tentative approval?

Tentative approval means the FDA has reviewed the generic drug application and found it scientifically acceptable, but approval is on hold due to patent litigation or exclusivity. Once the 30-month stay ends or the patent is invalidated, tentative approval becomes final, and the drug can be marketed immediately.

Why do generic companies still file Paragraph IV certifications if the process is so slow?

Because the first company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of market exclusivity - no other generics can enter during that time. That’s a massive financial incentive. Even with legal costs and delays, the potential profit from being first can be hundreds of millions of dollars.

Are biosimilars affected by the 30-month stay?

No. Biosimilars are regulated under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), which has a different framework. It provides 12 years of data exclusivity but does not include a 30-month stay mechanism. Patent disputes for biosimilars are handled through separate legal procedures, without automatic FDA approval delays.

Bottom Line

The 30-month stay isn’t broken - it’s being used differently than intended. It was designed to give innovators time to defend legitimate patents. Now, it’s often a shield for patent thickets and strategic delays. The real question isn’t whether the stay should exist - it’s whether it should be used to block competition for years after a patent should have expired. Patients shouldn’t have to wait for affordable drugs because lawyers are still in court. The system needs to catch up with the reality of modern drug development - and the cost of delay is measured in lives, not just dollars.Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

14 Comments

Donald Frantz November 20, 2025 AT 08:03

The 30-month stay isn’t a legal safeguard-it’s a corporate loophole dressed up as policy. Brand companies aren’t protecting innovation; they’re gaming the system with patent thickets on packaging and dosing schedules. If this were any other industry, it’d be called anticompetitive behavior. But drugs? We let them get away with it because patients are too desperate to fight back.

Sammy Williams November 22, 2025 AT 04:23

Man, I just got hit with a $600 co-pay for my dad’s diabetes med last month. Turned out the generic was approved 6 months ago but still wasn’t on shelves. No one told me why. Now I get it-manufacturers are waiting for the brand to settle or for the next lawsuit to drop. It’s insane we’re all just stuck in the middle of this.

Julia Strothers November 23, 2025 AT 07:51

This is all a scam. Big Pharma owns the FDA, the courts, and now Congress. The 30-month stay? A distraction. The real game is lobbying. They spent $100M in 2023 to keep this alive. Meanwhile, seniors are cutting pills in half. Who benefits? Not you. Not me. The same 5 CEOs who live in mansions and fly private. Wake up. This isn’t capitalism-it’s legalized theft.

Erika Sta. Maria November 24, 2025 AT 12:36

Wait… so the US spends more on drugs than anyone but has the worst access? That’s like paying $1000 for a pizza that tastes like cardboard. And you say the 30-month stay is the problem? Nah. It’s the whole system. Capitalism is dead. We are living in a simulation where profit > life. Also, India makes generics cheaper but we ban them? Hmm. Coincidence? I think not.

Nikhil Purohit November 24, 2025 AT 16:41

Really interesting breakdown. One thing I’ve seen in pharma forums: even when a generic gets approved, the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) often refuse to list it unless the brand pays them kickbacks. So even if the FDA says yes, the patient still can’t get it. The delay isn’t just legal-it’s financial middlemen playing games too.

Debanjan Banerjee November 26, 2025 AT 15:01

Let’s be clear: the 180-day exclusivity period is the real engine of this mess. It incentivizes the first filer to drag out litigation, not speed it up. Companies deliberately delay court rulings to maximize their monopoly window. That’s why 78% of generics report 6–9 month delays from litigation prep-it’s not bureaucracy, it’s strategy. The system rewards delay, not innovation.

Steve Harris November 28, 2025 AT 10:35

I appreciate how balanced this post is. The Hatch-Waxman Act was brilliant for its time, but it’s like using a 1984 flip phone in 2024. The core idea-balancing innovation and access-is still valid. But the tools? Outdated. We need to modernize the Orange Book, cap patent listings, and maybe even tie the stay length to actual patent validity, not just the filing of a lawsuit. Let’s fix it, not just rant about it.

Michael Marrale November 28, 2025 AT 15:50

They’re hiding something. You ever notice how every time someone tries to reform this, the CEO of a big pharma company suddenly gets appointed to a government advisory board? And then the bill dies? Coincidence? I don’t think so. There’s a shadow network here. The FDA? Controlled. Congress? Bought. The 30-month stay? Just the tip of the iceberg. They’re keeping us sick so they can keep selling.

David vaughan November 30, 2025 AT 15:13

Just wanted to say… this is so frustrating. I’ve got a kid with asthma. The inhaler? $400. Generic? Approved. But not available. Why? Because the brand company sued over a patent on the *mouthpiece design*. I’m not kidding. I cried reading this. We’re not talking about luxury drugs here. We’re talking about life-saving stuff. And we’re letting lawyers decide who lives and who doesn’t.

Sheldon Bazinga December 1, 2025 AT 02:44

Wow, so the US is the only country where you need a law degree to buy insulin? That’s rich. Meanwhile, Canada and India sell the same drugs for $10. Guess what? Our ‘innovation’ is just legal gymnastics. Also, ‘patent thickets’? That’s corporate speak for ‘we copied it 17 times and sued anyone who tried to copy us back.’ Classic American capitalism: exploit the loophole, then call it ‘intellectual property.’

Sandi Moon December 2, 2025 AT 14:23

One must observe, with the utmost intellectual rigor, that the 30-month stay is not a flaw but a feature of a deeply sophisticated market architecture. To dismantle it would be to invite chaos-a regression into the pre-1984 era of unregulated pharmaceutical anarchy. The notion that patients ‘deserve’ cheaper drugs is a moral fallacy; the market rewards risk, not need. One must ask: who funded the original R&D? Not the state. Not the patient. The private investor. And he must be protected.

Kartik Singhal December 2, 2025 AT 23:40

Bro… the real villain? The 180-day exclusivity. It’s like giving a trophy to the first guy who kicks down the door… then letting him charge $500 to let everyone else in. And the brand companies? They just sit back and wait for the first filer to crack. Then they pay them to disappear. Pay-for-delay = legal bribery. 🤡💸

Chris Vere December 4, 2025 AT 11:39

People forget that patents were never meant to be forever. They were meant to be temporary monopolies to encourage innovation. What we have now is a monopoly on monopoly. The system is broken not because it’s flawed-it’s because it’s been weaponized. We need to remember: medicine is a human right, not a profit metric. The math is simple: if you’re making billions while people ration pills, you’re not innovating-you’re exploiting.

Pravin Manani December 5, 2025 AT 18:29

From a regulatory science perspective, the 30-month stay creates a structural misalignment between the FDA’s technical review timeline and the legal adjudication timeline. The agency can achieve tentative approval in 12–18 months, yet the legal system operates on a 2–5 year cadence. This disconnect incentivizes generic applicants to optimize for litigation strategy over manufacturing readiness. The bottleneck isn’t the law-it’s the institutional inertia of a litigious ecosystem. Reform must target the legal-technical interface, not just the statute.