Health December 21, 2025

Opioid-Induced Constipation: How to Prevent and Treat It Effectively

When you start taking opioids for chronic pain, you’re often told to watch for drowsiness, nausea, or dizziness. But one of the most common and frustrating side effects? Constipation. In fact, opioid-induced constipation affects 40 to 60% of people taking these medications for non-cancer pain - and it doesn’t go away with time like other side effects. Unlike regular constipation, OIC doesn’t respond well to simple fixes. It’s a persistent problem that can make daily life miserable, and too many people suffer in silence because they don’t know what to do.

Why Opioid-Induced Constipation Is Different

Opioids don’t just block pain signals in your brain. They also bind to receptors in your gut, slowing everything down. The muscles in your intestines relax, your stomach empties slower, and your colon absorbs more water from stool, turning it hard and dry. Even worse, the anal sphincter tightens, making it harder to push out what’s there. This isn’t just "not eating enough fiber" - it’s a direct chemical effect. That’s why drinking more water or eating prunes often doesn’t help.People on long-term opioids often report straining, feeling like they haven’t fully emptied their bowels, or going less than three times a week. Left untreated, this can lead to bloating, nausea, loss of appetite, and even bowel obstruction. One study found that up to 100% of hospitalized cancer patients on opioids develop constipation. And while opioid prescriptions have dropped since 2012, over 73 million Americans still rely on them for chronic pain - meaning millions are at risk.

Prevention Starts on Day One

The biggest mistake? Waiting until you’re constipated to act. Experts agree: if you’re starting opioids, you should start a laxative the same day. Proactive treatment prevents 60 to 70% of severe cases. Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t hope it won’t happen. It will.For prevention, osmotic laxatives like polyethylene glycol (Miralax) are the go-to. They pull water into the colon without irritating the gut. Stimulant laxatives like senna or bisacodyl can be added if needed. Avoid stool softeners alone - they’re often too weak for OIC. Drink plenty of water (at least 2 liters a day), move regularly, and don’t ignore the urge to go. Even light walking helps stimulate bowel activity.

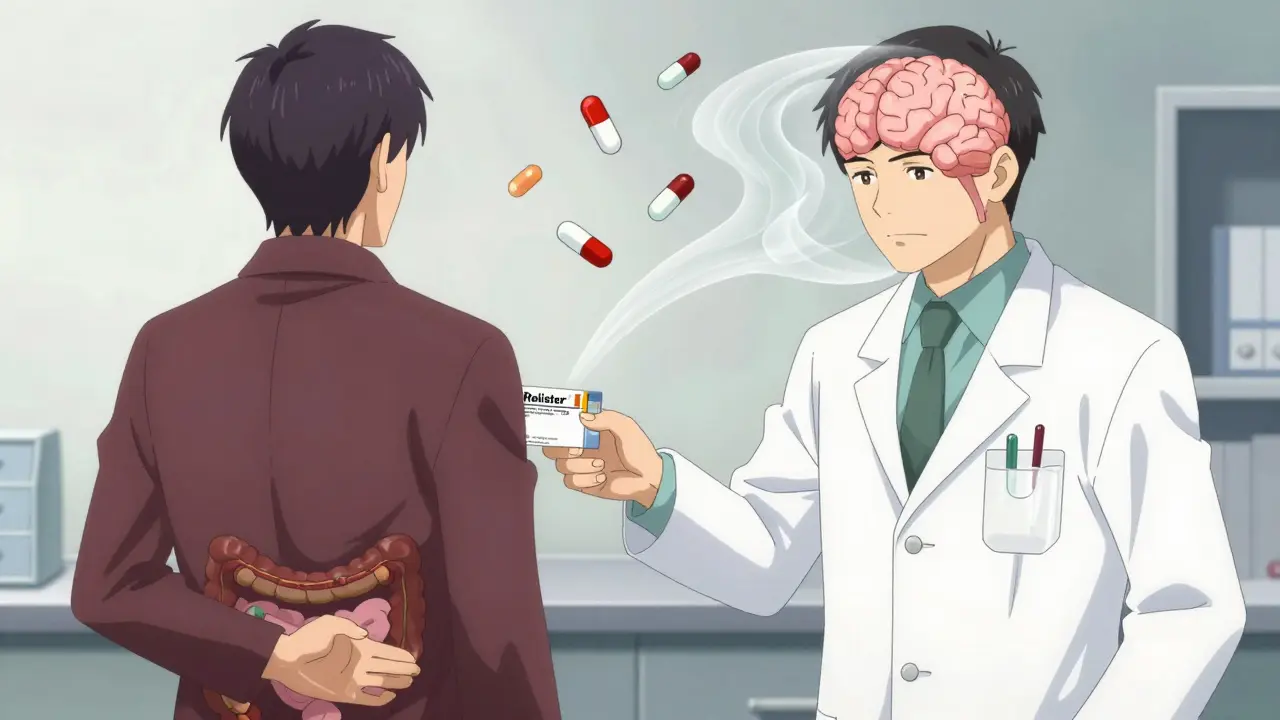

Pharmacists play a key role here. Studies show that when pharmacists proactively recommend laxatives when opioids are prescribed, patients are 43% more likely to start them. If your doctor doesn’t mention it, ask. Say: "I’ve heard constipation is common with these meds - what should I take from day one?"

When Laxatives Aren’t Enough

About 68% of patients say standard laxatives don’t fully help. That’s when you need to move to the next level: peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists, or PAMORAs. These are prescription drugs that block opioids from acting in the gut - without touching their pain-relieving effects in the brain.There are four main PAMORAs approved for OIC:

- Methylnaltrexone (Relistor®): Given as a daily injection or, since 2023, a once-weekly shot. Works in as little as 30 minutes. Often used for patients in palliative care.

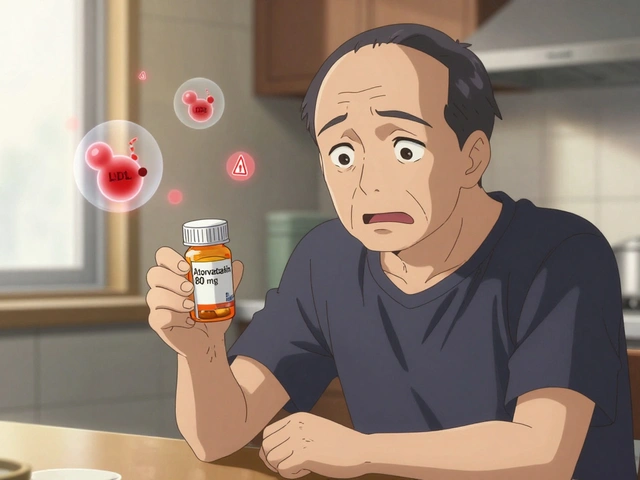

- Naldemedine (Symproic®): A daily pill. Approved by ASCO in 2024 for cancer patients because it may also reduce opioid-induced nausea and vomiting.

- Naloxegol (Movantik®): Another daily pill, often used for non-cancer chronic pain.

- Lubiprostone (Amitiza®): A chloride channel activator that increases fluid in the intestines. FDA-approved for women, but works in men too - though nausea is common.

These aren’t magic bullets. About 28% of users report abdominal pain as a side effect. And while many say things like, "Relistor saved my life," others stop taking them because of cost. A month’s supply can run $500 to $900 without insurance. Many Medicare and private plans require prior authorization or step therapy - meaning you have to try cheaper laxatives first, even if they’ve already failed.

Big Risks You Need to Know

PAMORAs are powerful, but they come with serious warnings. They’re contraindicated if you have a bowel obstruction or are at risk for one - like after recent abdominal surgery, or if you have Crohn’s disease or diverticulitis. In rare cases, these drugs can cause gastrointestinal perforation - a life-threatening tear in the gut wall. The FDA requires all PAMORAs to carry a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), meaning doctors must educate patients on the signs of perforation: sudden severe pain, fever, vomiting, or rigidity in the abdomen.Don’t ignore these signs. If you feel worse after starting a PAMORA, don’t wait. Go to the ER. It’s better to be safe than sorry.

Real Patient Experiences

Online forums are full of stories. On Reddit’s r/ChronicPain, one user wrote: "Naldemedine let me stay on my fentanyl patch without spending half my day in the bathroom." Another said: "I tried everything - Miralax, senna, enemas. Nothing worked. Relistor injection? 20 minutes later, I had my first normal bowel movement in months. It felt like getting my life back."But not everyone has that luck. A 2023 survey found that 57% of patients stopped PAMORAs within six months - mostly because of cost or lack of improvement. Some people respond well to one but not another. Trial and error is often needed. If one doesn’t work after two weeks, talk to your doctor about switching.

What’s Next? The Future of OIC Treatment

The global market for OIC treatments is growing fast - expected to hit $2.1 billion by 2027. Researchers are working on better options: oral PAMORAs with higher absorption, combination pills that mix low-dose laxatives with PAMORAs, and even personalized treatments based on genetics. One expert predicts that by 2026, we’ll be able to test a patient’s DNA to predict which drug will work best for them - cutting out the guesswork.Meanwhile, advocacy groups like the American Society of Gastroenterology are pushing for better insurance coverage. They estimate that poor OIC management costs the U.S. healthcare system $2.3 billion a year in avoidable ER visits, hospitalizations, and lost productivity.

Bottom Line: Take Control

Opioid-induced constipation isn’t something you just have to live with. It’s treatable - but only if you act early and know your options. Start a laxative on day one. Track your bowel movements. If you’re not having at least three soft, complete bowel movements a week, it’s time to talk to your doctor about PAMORAs. Don’t let fear of side effects or cost stop you. Ask about financial assistance programs. Many drug manufacturers offer co-pay cards or patient support services.And if your provider dismisses your concerns? Get a second opinion. You deserve to manage your pain without being trapped by your bowels. OIC is common. It’s serious. And it’s fixable - if you know how to fight it.

Is opioid-induced constipation the same as regular constipation?

No. Regular constipation often responds to fiber, water, or mild laxatives. Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is caused by opioids directly slowing gut movement and tightening the anal sphincter. It’s mechanistically different and usually doesn’t improve with lifestyle changes alone. Most people need targeted treatment like osmotic laxatives or PAMORAs.

Can I just use over-the-counter laxatives forever?

You can start with OTC laxatives - and you should. But if they don’t give you regular, comfortable bowel movements after a few weeks, they’re not enough. OIC is stubborn. Continuing with ineffective doses can lead to worsening symptoms and complications. If you’re still struggling, it’s time to talk about prescription options like PAMORAs.

Do PAMORAs reduce pain relief?

No. That’s the whole point. PAMORAs are designed to block opioid receptors only in the gut, not in the brain. They don’t interfere with pain control. Studies confirm that patients maintain their pain relief while seeing major improvements in bowel function. If your pain gets worse after starting a PAMORA, it’s likely unrelated - talk to your doctor.

How do I know if I need a PAMORA?

If you’re on opioids and have fewer than three bowel movements a week, or if you’re straining, feeling incomplete after going, or using laxatives daily without relief, you likely need more than OTC options. Doctors often use the Bowel Function Index (BFI) - a simple questionnaire. A score above 30 means significant constipation that needs stronger treatment.

Are PAMORAs covered by insurance?

It varies. Many plans require prior authorization or step therapy - meaning you must try cheaper laxatives first. About 41% of Medicare Part D plans and 28% of commercial plans impose these barriers. Some drug makers offer patient assistance programs to reduce out-of-pocket costs. Ask your pharmacist or the manufacturer’s website for help.

Can I take PAMORAs if I’ve had bowel surgery?

Not without caution. PAMORAs are contraindicated in people with known or suspected bowel obstruction, recent abdominal surgery, or conditions like Crohn’s disease or diverticulitis. These increase the risk of gastrointestinal perforation - a serious complication. Always tell your doctor your full medical history before starting any PAMORA.

What’s the fastest way to relieve OIC symptoms?

Methylnaltrexone (Relistor) injection works in as little as 30 minutes and is often used for acute relief. Oral PAMORAs like naldemedine or naloxegol take 1-2 days to show full effect. For immediate relief while waiting, a fleet enema or suppository may help - but these are temporary fixes. Long-term control requires consistent treatment.

Is there a natural remedy that works for OIC?

No proven natural remedy reliably treats OIC. Fiber, prunes, probiotics, and hydration help with general constipation but rarely fix OIC alone. Opioids override these effects. While they’re still good to include in your routine, don’t rely on them. If you’re constipated on opioids, medical treatment is necessary.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

14 Comments

Ajay Brahmandam December 22, 2025 AT 06:41

Been on opioids for 5 years for back pain. Started Miralax day one like the article says. Still go maybe 3x a week but no more agony. Best advice I got was from my pharmacist - not my doctor. Ask for help, don’t suffer silently.

Cara Hritz December 22, 2025 AT 23:30

omg i had no idea opioids did this like… permanently?? i thought it was just me not eating veggies 😭 i started senna and now i’m scared to stop

Art Van Gelder December 24, 2025 AT 05:42

Let me tell you something about the pharmaceutical industry. They don’t want you to know this, but PAMORAs were invented because they make more money than laxatives. The FDA? Complicit. Insurance companies? In on it. You think they care about your bowel movements? No. They care about your co-pays. Relistor costs $900 a month? That’s not medicine - that’s extortion dressed in white coats. And don’t get me started on the REMS program. It’s not safety - it’s liability theater. They’d rather scare you than solve it.

Jim Brown December 25, 2025 AT 16:20

There is a metaphysical dimension to opioid-induced constipation that few acknowledge. The body, in its wisdom, resists the chemical suppression of pain by immobilizing its own pathways - a silent rebellion of the gut against the mind’s surrender to pharmacological control. To treat OIC merely as a physiological malfunction is to ignore its symbolic weight: the body’s refusal to be fully colonized by the pharmaceutical state. One must ask not only, ‘How do I move my bowels?’ but also, ‘What is my body trying to tell me by refusing to release?’

Aliyu Sani December 27, 2025 AT 13:12

man i been on oxycotin for 8 years and i swear if i didnt start naldemedine last year i woulda died from blockage. its not a joke. i used to take 3 senna tabs a day and still felt like i had bricks inside. now i take one pill, poof - like a river broke loose. but yeah the price? insane. my cousin in naija said they get it cheaper there but i cant fly there every month lol

Nader Bsyouni December 27, 2025 AT 16:18

Why are we treating constipation like a medical emergency? Maybe the real problem is that people are too lazy to walk or eat real food. Why do we need a $900 pill when prunes exist? This is what happens when you outsource your biology to Big Pharma

jenny guachamboza December 28, 2025 AT 14:50

THEY’RE LYING ABOUT PAMORAS!!! 🚨 I read on a forum that they’re secretly linked to 5G and the government is using them to track people’s bowel movements. Also, why is Lubiprostone only FDA-approved for women? 👀 Are men just not important enough to have working intestines? #OpioidConspiracy #BowelSurveillance

Sam Black December 29, 2025 AT 05:57

As someone who’s lived in three countries and seen healthcare systems from India to Australia, I’ve noticed something: in places where pharmacists are integrated into primary care - like here in Australia - OIC is managed far better. Patients don’t wait until they’re in agony. They’re counseled on day one. The U.S. system treats constipation like a personal failure. It shouldn’t be that way.

Johnnie R. Bailey December 30, 2025 AT 15:53

My dad’s on fentanyl for spinal stenosis. We started him on Miralax and walking 20 minutes after dinner. After three weeks, he was having regular BMs without anything else. I know it sounds too simple - but the science backs it. Movement + osmotic laxative + hydration = 70% success rate. Don’t overcomplicate it. And if your doctor doesn’t bring it up? Bring it up for them. You’re not being annoying - you’re being smart.

Julie Chavassieux December 31, 2025 AT 06:23

...I just... I can’t... I’ve been on Relistor for 11 months and I still cry when I think about how I used to sit on the toilet for 45 minutes... and then... and then... nothing... and now... I just... I can go... and it’s... normal...

Tarun Sharma December 31, 2025 AT 11:26

Proactive laxative use is standard of care. Delaying intervention increases risk of complications. Recommend adherence to clinical guidelines.

Sai Keerthan Reddy Proddatoori January 1, 2026 AT 04:22

Why are we giving pills to Americans who can’t even eat vegetables? In India we eat dal and roti and still have bowel problems. This is a Western problem. Stop blaming the medicine. Blame the junk food. Also, why do we trust American doctors? They prescribe opioids like candy.

Vikrant Sura January 2, 2026 AT 16:24

So what? People get constipated. Big deal. Maybe they shouldn’t have taken opioids in the first place.

Jamison Kissh January 4, 2026 AT 03:02

What’s interesting is how this mirrors our broader relationship with medicine. We treat symptoms, not systems. We give pills for constipation but don’t ask why the body shut down in the first place. Opioids don’t just slow the gut - they slow everything. The mind. The spirit. The sense of agency. Maybe the real solution isn’t another drug, but a reevaluation of pain itself. Are we managing pain - or numbing existence? And if so… at what cost?