Health December 10, 2025

Alzheimer’s Disease: Understanding Memory Loss, Progression, and Today’s Treatments

When someone forgets where they put their keys-or worse, forgets their own child’s name-it’s easy to brush it off as normal aging. But when memory loss starts to interfere with daily life, it’s not just forgetfulness. It’s Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, affecting over 7 million Americans aged 65 and older in 2025. And that number is climbing. By 2060, it could hit nearly 14 million. This isn’t just about losing a name or a date. It’s about losing the ability to recognize your own home, speak coherently, or even swallow food. The brain changes slowly, silently, and irreversibly. But today, for the first time, we have real tools to slow it down-not just manage symptoms.

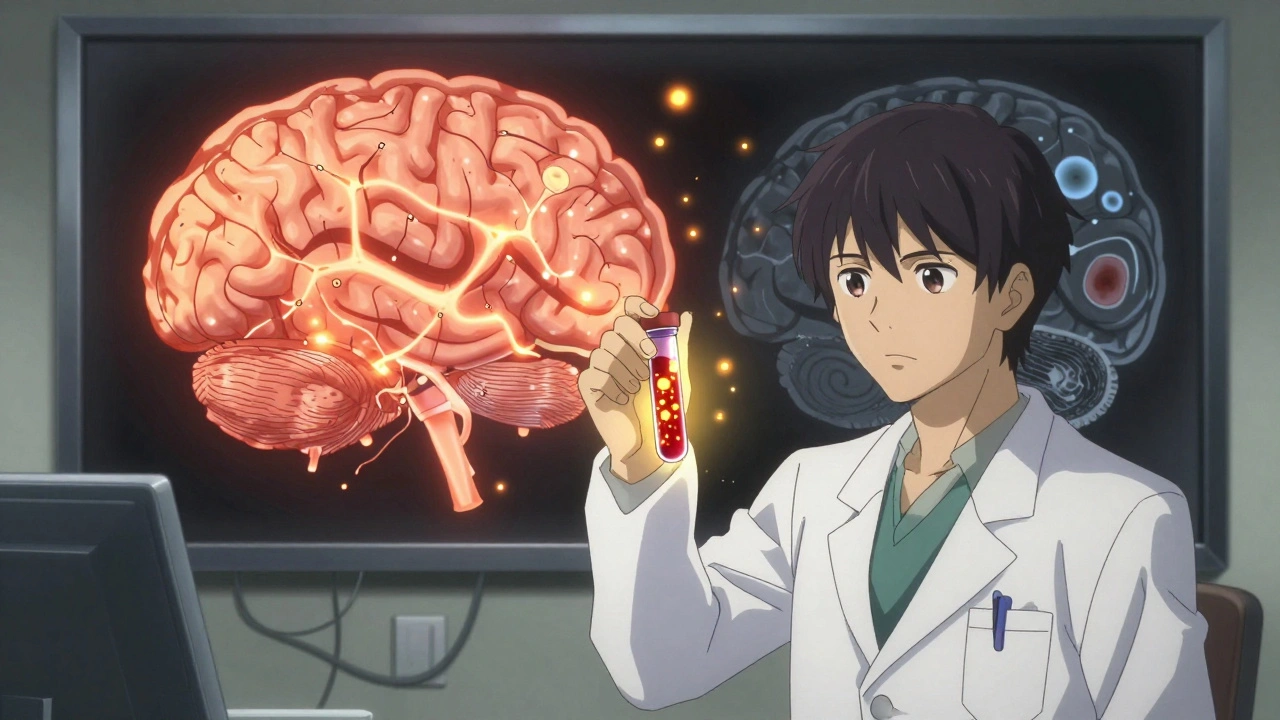

What Happens in the Brain?

Alzheimer’s doesn’t start with forgetting names. It starts with microscopic damage inside the brain. Two abnormal proteins build up: beta-amyloid forms sticky clumps called plaques between nerve cells, and tau twists into tangled threads inside them. These plaques and tangles choke off communication between brain cells, especially in the hippocampus-the area responsible for forming new memories. Over time, neurons die. Brain tissue shrinks. By the final stages, the brain can be up to 15% smaller than normal.These changes begin years, even decades, before symptoms show. That’s why doctors now use biomarkers to detect Alzheimer’s early. A spinal fluid test can spot low levels of amyloid-beta 42 and high levels of phosphorylated tau-with 85-90% accuracy. Amyloid PET scans show those plaques directly, with 92% specificity. Tau PET scans are newer but still growing in use. And now, a simple blood test called PrecivityAD2 can match PET scan results with 97% accuracy. That’s a game-changer. Instead of waiting for full-blown dementia, we can now identify the disease before the person even knows something’s wrong.

The Seven Stages of Progression

Alzheimer’s doesn’t hit all at once. It creeps in, then climbs. Experts break it into seven stages:- Stage 1: No impairment-Brain changes are happening, but nothing shows up in behavior or testing.

- Stage 2: Very mild decline-Occasional forgetfulness, like misplacing glasses. Often dismissed as stress.

- Stage 3: Mild decline-Friends or family notice memory lapses. Forgetting names, repeating questions, trouble planning a trip.

- Stage 4: Moderate decline-Now it’s clear. Trouble managing money, forgetting recent events, getting lost in familiar places. This is often when people get diagnosed.

- Stage 5: Moderately severe decline-Needs help with daily tasks. May not remember their address or phone number. Confused about time or season.

- Stage 6: Severe decline-Forgets close family members. Needs help dressing, bathing, using the toilet. May wander. Hallucinations or paranoia can appear.

- Stage 7: Very severe decline-Loses ability to speak. Can’t walk or sit up without help. Swallowing becomes dangerous. Full-time care is required.

On average, people live 4 to 8 years after diagnosis-but some survive 20 years. The speed depends on age at diagnosis, overall health, and whether they get early, targeted treatment.

Current Medications: What Works and What Doesn’t

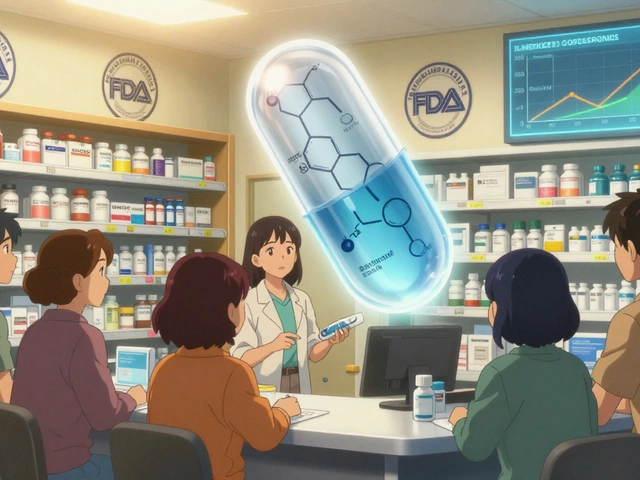

For decades, the only options were drugs that barely slowed symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors-donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine-boost a brain chemical called acetylcholine. They help about half of patients maintain thinking skills for 3 to 6 months. Memantine, an NMDA blocker, helps in moderate to late stages by regulating glutamate, a brain signal that can become toxic. But neither stops the disease. They’re like putting a bandage on a broken bone.Then came the breakthroughs. In January 2025, the FDA gave full approval to lecanemab (brand name Leqembi). It’s a monoclonal antibody that clears amyloid plaques. In a trial of nearly 1,800 people, it slowed cognitive decline by 27% over 18 months. Donanemab, another antibody, showed a 35% slowdown in a separate study. These aren’t cures. But they’re the first drugs proven to change the disease’s path.

There’s a catch. These drugs come with risks. About 1 in 8 people on lecanemab develop ARIA-amyloid-related imaging abnormalities. That means swelling or tiny bleeds in the brain. It’s usually mild and goes away, but it requires monthly MRI scans to monitor. Donanemab’s ARIA rate is even higher-24%. And the cost? Around $26,500 a year. Insurance doesn’t always cover it. Many patients get denied.

Then there’s ALZ-801, an oral drug for people with two copies of the APOE-e4 gene (the strongest genetic risk factor). In trials, it cut cognitive decline by 81% in this group. That’s huge. It’s not approved yet, but it’s on track for 2026. For people with this genetic profile, a pill could soon be better than an IV infusion.

Non-Drug Approaches That Actually Help

Medications aren’t the whole story. In fact, they’re only part of it. The FINGER study-a landmark trial from Finland-showed that combining diet, exercise, cognitive training, and managing blood pressure and cholesterol reduced cognitive decline by 25% over two years. People didn’t need drugs. They just changed how they lived.Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST), where people engage in group activities like memory games, music, and discussions, improved scores on memory tests by 1.5 points on average. That might sound small, but for someone with Alzheimer’s, it means remembering a meal, recognizing a photo, or holding a conversation. It’s meaningful.

And then there’s the biggest opportunity: prevention. Dr. Carol Brayne from Cambridge University says up to 40% of dementia cases could be avoided by managing nine modifiable risks: high blood pressure, obesity, hearing loss, smoking, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, low education, and social isolation. Hearing loss? It’s not just about missing jokes. Untreated hearing loss forces the brain to work harder to process sound, draining resources needed for memory. Treating it with hearing aids cuts dementia risk by nearly a third.

The Real Barriers: Access, Cost, and Caregiver Burnout

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: even if these treatments work, most people can’t get them. Only 15% of eligible patients receive disease-modifying drugs. Why? Because they need specialized centers with MRI machines, neurologists trained in Alzheimer’s, and teams that can manage side effects. In the U.S., 78% of these centers are in cities. Rural patients have to drive hours-or skip treatment.Insurance is another wall. Medicare covers lecanemab, but only under strict rules: patients must join a national registry, get monthly MRIs, and be monitored by certified clinics. Many families report being turned down. One caregiver on Reddit said, “We got approved for the drug, but not for the MRIs. So we’re stuck.”

And then there’s the caregiver burden. Eighty-five percent of family caregivers report emotional stress. Forty percent meet the criteria for depression. Many quit jobs or cut hours. The average annual income loss is $18,200. The emotional toll is worse. “I used to read to my wife every night,” said a man from Ohio. “Now she doesn’t know who I am. I still read. I just don’t expect her to answer.”

There’s also a glaring lack of diversity. In amyloid drug trials, only 8% of participants are Black, Hispanic, or Asian-though these groups make up 24% of Alzheimer’s cases in the U.S. That means we don’t know if these drugs work the same for everyone. We’re treating a disease based on data from mostly white, well-educated patients.

What’s Next? The Future Is Personalized

The field is shifting. No longer is Alzheimer’s seen as one disease with one cause. It’s a collection of subtypes-with different genetic triggers, different pathways, and different responses to treatment. That’s why experts now talk about precision medicine.By 2030, doctors may test your blood for amyloid, tau, inflammation markers, and APOE status. Then, they’ll match you to a treatment: an antibody if you have high amyloid, an anti-inflammatory if you have brain swelling, a metabolic therapy if your cells can’t use energy properly. Combination therapies are already in 27 active trials-amyloid drugs paired with tau blockers, or inflammation fighters.

And the tools are getting cheaper. Blood tests like PrecivityAD2 could cut diagnostic costs from $5,000 to $500. That means earlier detection in primary care offices, not just big hospitals. Community clinics could start screening seniors during annual checkups. Imagine: a simple blood draw at 65, and if the result flags risk, you get lifestyle coaching or early intervention before memory fails.

The goal isn’t just to slow decline. It’s to delay it long enough that people live out their lives with dignity. To let someone remember their grandchild’s birthday. To say “I love you” without confusion. To stay in their own home, not a nursing facility.

We’re not there yet. But for the first time, we have a path forward. Not just hope. Science.

Can Alzheimer’s be cured?

No, Alzheimer’s cannot be cured yet. But new disease-modifying drugs like lecanemab and donanemab can slow cognitive decline by 25-35% over 18 months. These treatments target the underlying brain changes, not just symptoms. While they don’t reverse damage, they give people more time with their memories, independence, and relationships.

How do I know if it’s Alzheimer’s or just normal aging?

Normal aging means forgetting where you put your keys and remembering later. Alzheimer’s means forgetting what keys are used for, or not recognizing your own home. If someone starts repeating questions, getting lost in familiar places, having trouble with money, or showing personality changes like suspicion or withdrawal, it’s not normal. See a doctor. Early testing with blood biomarkers or PET scans can confirm if it’s Alzheimer’s or another condition like depression or vitamin deficiency.

Are the new Alzheimer’s drugs worth the cost and risk?

It depends. For someone in the early stage with confirmed amyloid buildup and no major health risks, the 27-35% slowing of decline can mean months or years of better function. But the drugs cost $26,500 a year, require monthly MRIs, and carry a 12-24% risk of brain swelling or bleeding. For some, the burden outweighs the benefit. For others, especially those with the APOE-e4 gene, the newer oral drug ALZ-801 may offer similar benefits with fewer side effects. Talk to a specialist about your individual risks and goals.

Can lifestyle changes really prevent Alzheimer’s?

Yes. The FINGER study showed a 25% reduction in cognitive decline with a combination of healthy diet (Mediterranean-style), regular exercise (150 minutes a week), cognitive training, and managing blood pressure and cholesterol. Other studies link hearing aids, sleep quality, and social engagement to lower risk. It’s not about one miracle habit-it’s about managing your brain’s health like you would your heart. Even starting in your 50s makes a difference.

What should I do if a loved one is diagnosed?

First, get a full diagnostic workup-blood tests, brain imaging, cognitive assessment. Then connect with the Alzheimer’s Association’s 24/7 Helpline (1.800.272.3900). They offer free care planning, support groups, and referrals to local services. Consider joining a caregiver training program. Learn how to communicate when words fail, how to handle wandering, and how to protect against falls. Most importantly, take care of yourself. Caregiver burnout is real. You can’t help someone if you’re broken.

Is Alzheimer’s hereditary?

Most cases-90%-are late-onset and not directly inherited. But having one copy of the APOE-e4 gene increases risk 3-4 times. Two copies raise it up to 15 times. Early-onset Alzheimer’s (before 65) is rare and often linked to specific gene mutations passed down in families. If multiple close relatives had Alzheimer’s before 65, genetic counseling may be helpful. But for most people, genes aren’t destiny. Lifestyle and vascular health matter more.

Where to Go From Here

If you’re worried about memory changes in yourself or someone else, don’t wait. See a doctor. Ask for a blood test for Alzheimer’s biomarkers. If you’re a caregiver, reach out to the Alzheimer’s Association. Attend a support group. Learn the signs of ARIA if someone is on a new drug. Advocate for better access in your community.The future of Alzheimer’s care isn’t just in labs or hospitals. It’s in primary care clinics, in hearing aid fittings, in walking groups for seniors, in meals shared with friends. It’s in recognizing that memory isn’t just a brain function-it’s the foundation of identity, love, and connection. And we’re finally learning how to protect it.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

15 Comments

Ariel Nichole December 12, 2025 AT 10:33

Really appreciate this breakdown. I’ve been watching my dad slip away over the last few years, and this article finally put words to what we’ve been feeling. The part about hearing aids reducing risk? My mom got hers last year and he actually laughs at jokes again. Small wins matter.

Also, the blood test thing blew my mind. No more waiting for total collapse. We’re getting him tested next week.

john damon December 13, 2025 AT 17:36

OMG YES 🙌 I’ve been begging my uncle to get checked for 3 years. He thinks it’s just ‘getting old’ but he forgot my birthday last year AND tried to put his phone in the fridge. 😭 Time to push harder.

matthew dendle December 13, 2025 AT 22:21

So we spend 26k a year to slow someone down by 27%… and the drug gives them brain bleeds? Wow. Real brilliant. Guess we’re just gonna keep pretending money solves biology. Meanwhile grandma’s still taking ginkgo and praying.

Also why is everyone acting like this is new? I’ve been yelling about amyloid since 2012. Nobody listened.

Also why are we calling it a disease when it’s just what happens when you live too long? Just let people die already.

Kristi Pope December 14, 2025 AT 13:03

Reading this made me cry not because it’s sad but because it’s so clear. We’ve been treating Alzheimer’s like a mystery when it’s really a slow-motion tragedy we could’ve prevented.

My aunt didn’t get hearing aids until it was too late. Now she sits in silence at family dinners. I wish we’d known sooner.

But here’s the thing - we’re not powerless. Eat well. Move. Stay connected. Even if you’re 50, it’s not too late. Your brain still listens.

And if you’re scared? You’re not alone. We’re all just trying to hold on to the people we love.

One step at a time.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt December 15, 2025 AT 19:00

This is one of those rare posts that doesn’t just inform - it makes you feel less alone. I’ve been a caregiver for seven years now. Some days I feel like I’m drowning. Other days, like when my wife smiles at a song from her youth, I remember why I’m still here.

The science is moving fast, sure. But what keeps me going isn’t the drugs or the scans - it’s the quiet moments. The hand-holding. The singing off-key in the kitchen.

Maybe we can’t stop the fade. But we can make sure the light stays on a little longer.

Lisa Stringfellow December 17, 2025 AT 13:09

Wow. Another feel-good piece about Alzheimer’s that ignores the real problem: we’re wasting billions on rich people’s brain drugs while nursing homes are understaffed and Medicaid won’t cover a single MRI.

And don’t even get me started on how these ‘breakthroughs’ only work for white people in clinical trials. Real people? We’re just supposed to pray and hope the system doesn’t collapse before our loved ones do.

Thanks for the sugar-coated science. I’ll be over here watching my mom forget how to use a fork.

Jean Claude de La Ronde December 17, 2025 AT 21:25

So the solution to dementia is more expensive scans, more IVs, and more corporate profits? Brilliant. In Canada we just give them tea and call it a day. No MRI needed. Just love and a warm blanket.

Also, why are we so obsessed with ‘slowing decline’? Why not just accept that forgetting is part of being human? We turn aging into a medical emergency because we’re terrified of death.

Maybe the real cure is learning to let go.

Jim Irish December 18, 2025 AT 03:53

Important information presented clearly. Early detection saves dignity. Access must improve. Caregiver support is non-negotiable. Prevention through lifestyle is proven. These are not just medical issues - they are societal responsibilities.

Thank you for the clarity.

Mia Kingsley December 19, 2025 AT 01:23

Wait so you’re telling me if I’m rich and white and have the right genes I get a magic pill but if I’m poor or brown I get told to eat kale and do crossword puzzles? Yeah right.

Also I read somewhere that Alzheimer’s is caused by fluoride in the water so I’m just gonna drink spring water and ignore all this science.

Also my cousin’s dog has better memory than my uncle now. Coincidence? I think not.

Katherine Liu-Bevan December 20, 2025 AT 01:29

Let me clarify something that’s being glossed over: lecanemab and donanemab only work for people with confirmed amyloid pathology. That’s why biomarker testing is critical - not just for treatment, but to rule out other causes like vascular dementia, depression, or thyroid issues.

Many people get misdiagnosed. A simple blood test can prevent years of unnecessary stress and wrong treatments.

Also, the FINGER study isn’t just ‘eat healthy’ - it’s structured, supervised, and tailored. Not just ‘go for a walk.’ That’s why it worked.

And yes, the cost is insane. But if we invest in early detection now, we’ll save billions later in long-term care.

Courtney Blake December 20, 2025 AT 13:00

Oh great. More American medical imperialism. We spend 10x more per capita on healthcare than Canada or Germany and still can’t fix this? Of course the drugs work - they’re designed for privileged white patients in Boston.

Meanwhile, my grandma in Alabama can’t even get a primary care doctor who knows what amyloid is.

And don’t even get me started on how they exclude Black patients from trials and then act surprised when the drugs don’t work the same.

This isn’t science. It’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

Aman deep December 21, 2025 AT 07:53

As someone from India, I’ve seen both worlds - families caring for elders at home with love, and hospitals where Alzheimer’s is ignored because it’s ‘just old age.’

But here’s the truth: even in villages, people remember songs, smells, faces - long after they forget names. Memory isn’t just in the brain. It’s in the rituals, the food, the lullabies.

Maybe the West is over-medicalizing what’s also a cultural loss.

Still - if we can give someone more time to hear their grandchild’s laugh? That’s worth every penny.

And yes, hearing aids matter. My grandfather started hearing again at 78. He cried when he heard his wife’s voice for the first time in years.

Eddie Bennett December 22, 2025 AT 18:49

I’ve been sitting here reading this and just… nodding. My mom’s in stage 5. She doesn’t know my name anymore, but she still hums the same tune from her wedding day.

They talk about drugs and scans and costs, but what no one says is that the hardest part isn’t the forgetting - it’s watching someone disappear while you’re still here.

So I keep reading to her. Even when she doesn’t answer.

Because maybe, just maybe, she still hears me.

Sylvia Frenzel December 23, 2025 AT 16:12

This is the most manipulative article I’ve read all year. They make you feel guilty if you don’t spend $26k on a drug that gives you brain bleeds. They make you think if you don’t do yoga and eat kale your grandma will die faster.

Meanwhile, the real problem? No one cares about elderly people unless they’re profitable.

Also, why are all the ‘experts’ in this article white? Where are the Black and Hispanic researchers? Oh right - they’re not invited to the party.

Thanks for the performative compassion. I’ll pass.

Paul Dixon December 23, 2025 AT 18:07

Just wanted to say thank you. This didn’t feel like a medical textbook. It felt like someone finally told the truth - messy, hard, and full of hope.

My wife was diagnosed last year. We’re on the waiting list for lecanemab. Got denied twice. Now we’re trying to get into a trial.

It’s not about the drug. It’s about not giving up.

And yeah - I still read to her every night.

She doesn’t respond.

But I do.