Health February 7, 2026

QT Prolongation and Sudden Cardiac Death: Key Medication Risk Factors

QT Prolongation Risk Assessment Tool

How This Tool Works

This tool helps assess your risk of QT prolongation based on medications you're taking and your individual health factors. It calculates a risk score and provides personalized recommendations.

Important: This tool is for educational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice. Always consult your healthcare provider.

Risk Assessment Results

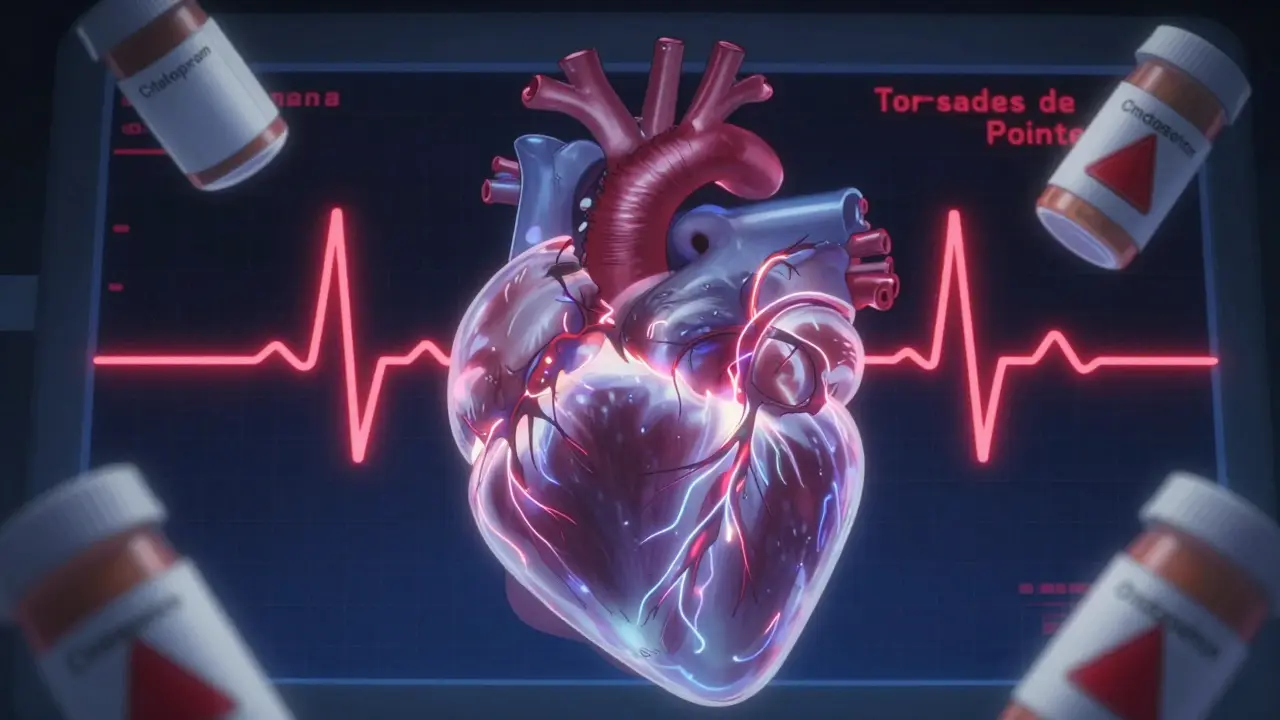

Every year, people die from a hidden side effect of medications they never thought could hurt them. It’s not an overdose. It’s not an allergic reaction. It’s something invisible on the surface: a tiny delay in the heart’s electrical reset, called QT prolongation. Left unchecked, this delay can spiral into a deadly rhythm called Torsades de Pointes - and then, sudden cardiac death.

This isn’t theoretical. It’s happened to real people. In 1997, the antihistamine terfenadine (Seldane) was pulled off shelves after dozens of deaths. In 2002, the antibiotic erythromycin sent patients to the ER with heart rhythms that looked like a jagged mountain range on an ECG. Even common drugs like citalopram, used for depression, can push the QT interval into danger zones - especially when combined with other meds or in people with existing heart issues.

What Exactly Is QT Prolongation?

The QT interval on an ECG measures how long it takes the heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) to recharge after each beat. Think of it like a battery resetting after firing. If that reset takes too long - more than 450 milliseconds in men, or 470 in women - the heart becomes electrically unstable. That’s QT prolongation.

But here’s the catch: measuring it isn’t as simple as reading a number. Automated ECG machines can be off by up to 40 milliseconds. Manual readings by trained technicians are more accurate, but they’re not always done. That’s why some patients get flagged for high risk when they’re actually fine - and others slip through the cracks.

The real danger comes when the heart’s electrical recovery becomes uneven across different areas. One part of the ventricle recharges slowly while another snaps back quickly. That imbalance can trigger a chaotic, self-sustaining rhythm - Torsades de Pointes. It often looks like a twisting peak on the ECG. If it doesn’t stop on its own, it can turn into ventricular fibrillation… and then death.

Which Medications Carry the Highest Risk?

Over 100 prescription drugs are known to prolong the QT interval. But not all are created equal. Some are far more dangerous than others.

Class III antiarrhythmics - drugs like dofetilide and sotalol - are designed to slow the heart’s electrical activity. But that’s their flaw. Dofetilide, for example, causes Torsades de Pointes in about 3.3% of patients even at standard doses. Sotalol has the same problem, and it’s worse at slow heart rates - a dangerous combo for people with bradycardia.

Antibiotics are another big concern. Moxifloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) can push the QTc up by 6 to 15 milliseconds on average. That might sound small, but in someone with low potassium or on another QT-prolonging drug, it’s enough to tip the scales. Ciprofloxacin? Barely any effect. Erythromycin? It doubles the risk of sudden death - and if taken with a CYP3A4 inhibitor like ketoconazole or grapefruit juice? Risk jumps fivefold.

Antidepressants vary wildly. Citalopram at 40mg daily raises QTc by an average of 8.5ms. Escitalopram - its purified cousin - only adds 4.2ms. That’s why many doctors now switch patients from citalopram to escitalopram if they’re at risk. It’s not just about the drug class - it’s about the specific molecule.

Even anti-nausea drugs like ondansetron have been flagged. In healthy people? Low risk. In elderly patients on multiple meds? A different story.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about the person taking it.

Women are at higher risk than men - partly because their baseline QT interval is naturally longer. Older adults, especially those over 65, are vulnerable too. On average, they take nearly 8 medications. And 34% of them are on at least one QT-prolonging drug. Combine that with kidney or liver problems - which slow drug clearance - and you’ve got a perfect storm.

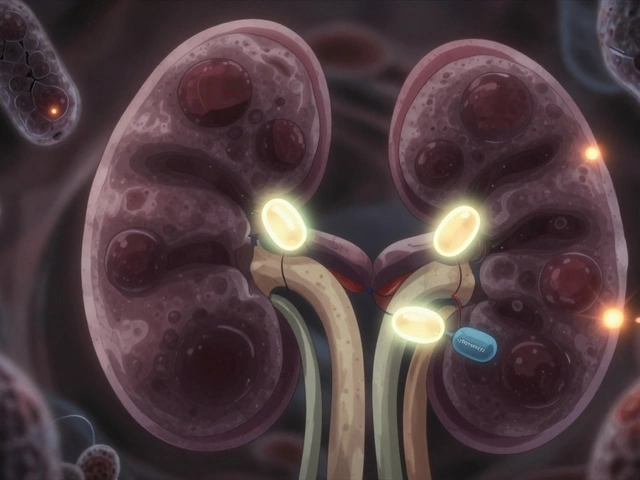

Electrolyte imbalances are a silent killer. Low potassium (hypokalemia) and low magnesium are major triggers. Studies show correcting potassium to above 4.0 mEq/L cuts QT prolongation risk by 62%. Low magnesium? Even worse. Many hospitals now check both before giving drugs like sotalol or dofetilide.

Structural heart disease changes everything. Someone with heart failure, a prior heart attack, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has a 10 to 100 times higher risk of sudden death from a QT-prolonging drug than someone with a healthy heart. That’s not a small increase. That’s a red flag.

And genetics? They matter more than we thought. Some people have inherited variants that make their hearts extra sensitive. The NIH’s All of Us program is now collecting genetic data from 1 million people to find these patterns. But right now, we don’t test for them routinely.

Drug Interactions: The Hidden Trap

One drug alone might be safe. Two together? That’s where the danger explodes.

CYP3A4 inhibitors - like ketoconazole, clarithromycin, grapefruit juice, and even some HIV meds - block the liver’s ability to break down other drugs. That means QT-prolonging medications build up in the bloodstream faster than expected. A patient on erythromycin might be fine. Add a single dose of ketoconazole? Risk spikes fivefold.

Same goes for CYP2D6 inhibitors - like fluoxetine or paroxetine - which affect antidepressants and antipsychotics. A patient on risperidone (an antipsychotic) might be stable. Add a SSRI that blocks CYP2D6? QTc jumps. And no one sees it coming.

That’s why tools like AZCERT.org exist. Updated weekly, it lists 212 medications by risk level: Known Risk, Possible Risk, Conditional Risk. Doctors can check combinations before prescribing. But many still don’t. In community hospitals, only 31% have formal QT monitoring protocols. At academic centers? 68%. The gap is real.

False Alarms and Overtesting

Here’s the irony: we’ve created systems to protect patients - and they’re overwhelming doctors.

Electronic health records now auto-flag high QTc values. At one hospital, 78% of those alerts were false positives. Residents get so used to ignoring them that they start tuning out entirely. That’s alarm fatigue. And it’s dangerous.

Some clinicians order ECGs for every patient on ondansetron - even if they’re young, healthy, and have no other risk factors. It’s unnecessary. It clogs the system. And it doesn’t save lives.

Patients, too, get scared. A 2021 survey found 22% of people on citalopram stopped taking it because they worried about QT prolongation. Only 3% of them actually had a QTc over 500ms. They traded a proven treatment for anxiety - and risked worsening depression.

What Should You Do?

If you’re a patient: Don’t panic. But do speak up. Tell your doctor about every medication you take - including supplements, OTC drugs, and herbal products. Mention if you’ve ever fainted, had palpitations, or have a family history of sudden death. Ask: “Could any of my meds affect my heart rhythm?”

If you’re a clinician: Use the 3-step MHRA approach.

- Check baseline QTc. Is it over 450ms (men) or 470ms (women)?

- Look for modifiable risks: potassium below 4.0? Magnesium low? Bradycardia? Kidney disease?

- Check for drug interactions. Use AZCERT.org or similar tools.

Don’t rely on automated alerts alone. Manual review still matters. And if you’re unsure - pause. Consult a cardiologist. The cost of a delay is far less than the cost of a death.

The Bigger Picture

The FDA and European regulators now require new drugs to be tested for T-wave shape changes - not just QTc length. That’s progress. The CiPA initiative, launched in 2013, uses human stem cell-derived heart cells to predict risk more accurately than old hERG channel tests. 92% of big pharma companies now use it.

And new tech is helping. In 2023, the FDA approved QTguard by Verily Life Sciences - an AI system that cuts false alarms by 53% by analyzing the full ECG waveform, not just the QT interval. It spots subtle changes in T-wave morphology that humans miss.

But technology alone won’t fix this. The real solution is awareness - and careful, personalized prescribing. We know the risks. We have tools. We just need to use them.

Because QT prolongation doesn’t discriminate. It doesn’t care if you’re young or old, rich or poor. It only cares if the numbers line up - and if someone was paying attention.

Can a normal ECG rule out risk of QT prolongation?

No. A single normal ECG doesn’t rule out risk. QT interval can change over time due to drug interactions, electrolyte shifts, or worsening heart disease. A normal reading today doesn’t mean it’ll stay normal tomorrow - especially if you start a new medication. Serial monitoring, especially in high-risk patients, is often needed.

Is QT prolongation always dangerous?

Not always. Mild prolongation (e.g., QTc 460-480ms) in a healthy person on a low-risk drug is rarely dangerous. But when combined with other factors - low potassium, heart disease, or interacting meds - even small changes can trigger life-threatening rhythms. Risk is cumulative. It’s not about the number alone - it’s about the context.

Can I take citalopram if I have a long QT interval?

Citalopram is generally avoided if QTc is over 450ms in men or 470ms in women. At doses above 40mg daily, the risk rises sharply. Escitalopram is a safer alternative - it causes about half the QT prolongation. If you need an antidepressant and have cardiac risk factors, your doctor should consider escitalopram, sertraline, or bupropion instead.

Do all antibiotics prolong the QT interval?

No. Only certain classes do. Fluoroquinolones like moxifloxacin and levofloxacin carry the highest risk. Macrolides like erythromycin and clarithromycin are also problematic. Azithromycin has a much lower risk. Penicillins, cephalosporins, and tetracyclines generally don’t affect the QT interval at all. Always check the specific drug, not just the class.

How long does it take for a drug to cause QT prolongation?

It varies. Some drugs cause changes within hours - especially when given IV. Others take days to build up, especially oral medications. The risk is highest in the first few days after starting a new drug or increasing the dose. That’s why monitoring is critical early on. For high-risk patients, ECGs are often repeated 2-5 days after starting a new QT-prolonging medication.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

14 Comments

THANGAVEL PARASAKTHI February 8, 2026 AT 03:43

man i never knew so many common meds could mess with your heart like this. i was on citalopram for years and never thought twice. guess i got lucky. still, this post is wild - like, we’re dosing people with drugs that can kill them silently and calling it medicine. scary stuff.

Frank Baumann February 9, 2026 AT 14:11

THIS IS WHY WE NEED TO STOP TRUSTING PHARMA. THEY DON’T CARE ABOUT YOU. THEY CARE ABOUT PROFITS. TERFENADINE WAS PULLED BECAUSE PEOPLE DIED - BUT HOW MANY OTHER DRUGS ARE STILL ON THE MARKET WITH THE SAME RISK? THEY KNOW. THEY JUST DON’T CARE. I’VE SEEN PATIENTS DROP DEAD FROM ‘SAFE’ MEDS. IT’S NOT AN ACCIDENT. IT’S A SYSTEMIC FAILURE. AND THEY’RE STILL SELLING THESE THINGS LIKE THEY’RE VITAMINS.

Scott Conner February 10, 2026 AT 05:08

so wait - if automated ecg machines are off by 40ms, and manual readings are better but rarely done… then how do we even know who’s actually at risk? feels like we’re playing russian roulette with prescriptions. also, why aren’t we testing for genetic sensitivity before prescribing? seems like the dumbest thing ever.

Alex Ogle February 10, 2026 AT 05:42

honestly, the most chilling part isn’t the drugs - it’s how normal people just take them without knowing. i had a friend on ondansetron after chemo, no ecg, no labs, no questions. she’s 29, healthy, no history. just… took it. and now? she’s terrified every time she gets nauseous. this isn’t medical care. it’s gambling with your heartbeat.

Brandon Osborne February 10, 2026 AT 07:47

YOU PEOPLE AREN’T THINKING ABOUT THIS RIGHT. IT’S NOT ABOUT ‘RISK’ - IT’S ABOUT ACCOUNTABILITY. DOCTORS AREN’T JUST ‘UNAWARE’ - THEY’RE LAZY. THEY DON’T CHECK INTERACTIONS. THEY DON’T REVIEW MEDS. THEY JUST CLICK ‘PRESCRIBE’ AND MOVE ON. AND THEN PEOPLE DIE. AND NO ONE GETS FIRED. NO ONE GETS SUED. THIS ISN’T NEGLIGENCE - IT’S CRIMINAL. WE NEED TO HOLD THESE PEOPLE RESPONSIBLE. NOT JUST ‘BE AWARE’ - CRIMINALIZE THE INDIFFERENCE.

MANI V February 10, 2026 AT 23:07

india has been dealing with this for decades. we don’t even have proper ecg machines in rural clinics. people take citalopram, antibiotics, and ayurvedic supplements together - and wonder why their uncle dropped dead at 58. no one tests potassium. no one checks liver function. just give the pill. this isn’t a ‘western problem’ - it’s a global failure of basic medical ethics.

Susan Kwan February 12, 2026 AT 20:13

so let me get this straight - we have AI systems that cut false alarms by 53%, but only 31% of community hospitals use formal QT protocols? wow. so we’re using futuristic tech… but still treating patients like 1980s lab rats. congrats, medicine. you’re basically a haunted house with a fancy sign.

Random Guy February 13, 2026 AT 22:49

my grandma took erythromycin + grapefruit juice. she’s fine. so is this all just fearmongering? or did she just get lucky? also, why is everyone so scared of citalopram but not xanax? that stuff’s a chemical wrecking ball. just saying.

Ryan Vargas February 15, 2026 AT 05:01

think deeper. this isn’t about drugs. it’s about the commodification of the human body. we reduced the heart to a number - QTc - and ignored the living system behind it. we don’t treat patients. we treat data points. the FDA’s ‘CiPA’ initiative? it’s still using lab-grown cells. we’re simulating life with petri dishes while real people die because a pharmacist didn’t check their meds. this is a spiritual crisis disguised as a medical one.

Jessica Klaar February 16, 2026 AT 06:00

i just wanted to say thank you for writing this. my mom had a near-death episode from a combo of citalopram and an antibiotic. we didn’t know anything. no one warned us. now she’s on escitalopram, her potassium’s monitored, and she’s doing okay. this post helped me understand what happened - and now i’m telling everyone i know. you saved lives just by writing this.

PAUL MCQUEEN February 16, 2026 AT 16:01

why are we even talking about this? we’ve got bigger problems. climate change. inflation. war. a few people dying from meds? that’s just the cost of modern life. if you can’t handle your prescriptions, maybe you shouldn’t be on them. also, i’m pretty sure this is just a way for cardiologists to make more money.

Angie Datuin February 16, 2026 AT 19:37

thank you for sharing this. i’ve been on sotalol for a year. my doctor checks my potassium every 3 weeks. i didn’t realize how rare that is. i feel lucky. and scared. but also… hopeful? knowing what to watch for makes me feel less powerless.

Camille Hall February 17, 2026 AT 20:37

one thing i wish more doctors did: ask about supplements. i took a ‘natural’ magnesium pill for sleep - didn’t know it was chelated, so it absorbed like crazy. my QTc spiked. no one asked. just because it’s ‘natural’ doesn’t mean it’s safe. this needs to be part of every med review.

Ritteka Goyal February 18, 2026 AT 00:51

india is the future of medicine. we don’t have time for all this fancy ecg nonsense. we give people pills, they take them, they live. if they die? well, that’s karma. also, why are you all so obsessed with west? we’ve been treating heart issues with turmeric and yoga since 3000 bce. maybe stop overcomplicating things. and also - grapefruit juice? in india we use lemon. it’s cheaper. and better.