Health December 28, 2025

Hyponatremia and Hypernatremia in Kidney Disease: What You Need to Know

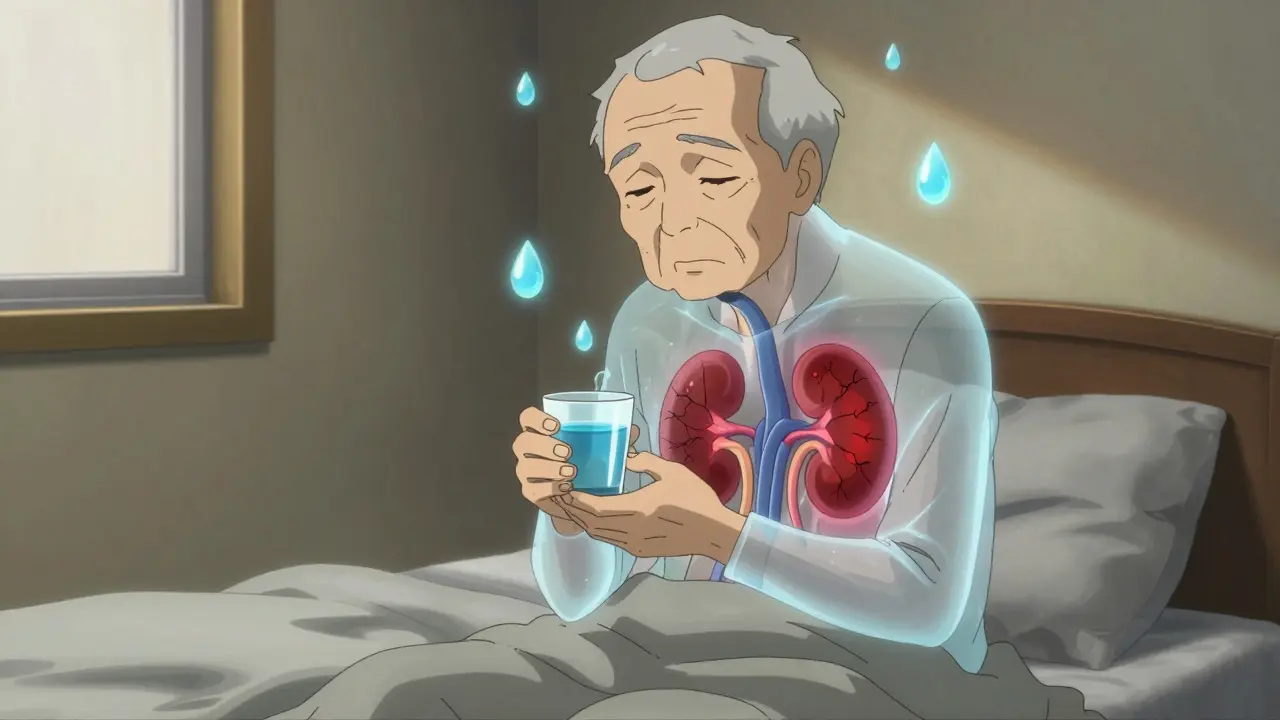

When your kidneys start to fail, even small changes in sodium levels can become dangerous. Hyponatremia (sodium below 135 mmol/L) and hypernatremia (sodium above 145 mmol/L) aren’t just lab numbers-they’re warning signs that your body’s water-sodium balance is breaking down. In people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), these conditions are far more common than most realize, affecting up to 25% of those with moderate to advanced kidney damage. And unlike healthy people, CKD patients can’t simply drink more water or eat more salt to fix it. Their kidneys have lost the ability to adapt.

Why Your Kidneys Can’t Keep Sodium in Check

Your kidneys normally adjust urine concentration to match how much sodium and water you take in. In early CKD (stages 1-2), they still manage this, but they have to work harder-producing more urine to flush out excess sodium. By stage 4 or 5, when the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) drops below 30 mL/min/1.73m², that system collapses. The kidneys can no longer make concentrated urine to save water or dilute urine to get rid of excess fluid. This is why even a small glass of extra water can push sodium levels dangerously low in someone with advanced CKD.The problem isn’t just about how much you drink. It’s about how your body handles sodium overall. In CKD, the kidneys can’t excrete sodium efficiently, so even normal salt intake leads to buildup. At the same time, the body’s signals to release or hold water-controlled by vasopressin (ADH)-get mixed up. Medications like thiazide diuretics, which are often used for high blood pressure, can make this worse. In fact, up to 30% of euvolemic hyponatremia cases in CKD patients are linked to these drugs.

Hyponatremia: The Silent Threat

Hyponatremia is the most common sodium disorder in CKD, making up 60-65% of cases. Many people don’t feel symptoms until it’s serious. Fatigue, confusion, nausea, and muscle cramps are easy to blame on aging or other conditions. But in CKD, even mild hyponatremia carries real risks. Studies show it doubles the chance of falling, increases fracture risk by 67%, and raises the risk of death by nearly 2 times compared to people with normal sodium levels.One dangerous myth is that eating less salt always helps. In reality, many CKD patients are told to cut sodium, potassium, and protein to manage other problems like high potassium or acidosis. But when you reduce solute intake too much, your kidneys can’t produce enough urine to excrete water. That’s when hyponatremia spikes. A 2023 Japanese study found that patients on strict solute-restricted diets had higher rates of low sodium-not lower.

There are three types of hyponatremia in CKD:

- Euvolemic (most common): Water builds up, sodium stays normal, but your total fluid volume is too high. This happens because your kidneys can’t pee out the extra water.

- Hypervolemic: You’re swollen with fluid-common in late-stage CKD or if you also have heart failure. Sodium is diluted because there’s too much water overall.

- Hypovolemic: You’ve lost both salt and water, but lost more salt. This can happen from overusing diuretics or rare salt-wasting syndromes.

Hypernatremia: When You’re Too Dry

Less talked about but just as dangerous is hypernatremia. It’s not usually from not drinking enough water-it’s from not being able to feel thirsty or not being able to get water to your body. In elderly CKD patients, who make up 70-75% of advanced cases, the brain’s thirst signal weakens. If they can’t reach a glass of water, or if they’re on medications that dry them out, sodium climbs.Hypernatremia in CKD often happens when a patient has a fever, infection, or is on a diuretic that pulls water out faster than sodium. The kidneys, already struggling, can’t hold onto water. Sodium levels above 145 mmol/L mean your brain cells are shrinking from dehydration. That can cause seizures, coma, or even death if corrected too quickly.

Correction speed matters. You can’t just flood someone with water. Rapid correction can cause cerebral edema-swelling in the brain. The rule is simple: lower sodium by no more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours. Too fast? Risk of brain damage. Too slow? Risk of ongoing organ stress.

What You Can Actually Do

There’s no one-size-fits-all fix. Treatment depends on your stage of CKD, your symptoms, and your volume status.For hyponatremia:

- Fluid restriction is the first step-but not the same for everyone. In early CKD, 1,000-1,500 mL/day is typical. In advanced CKD, it drops to 800-1,000 mL/day.

- Stop or switch thiazide diuretics if your GFR is below 30. Loop diuretics like furosemide are safer and more effective at this stage.

- Don’t rush correction. Raise sodium by no more than 4-6 mmol/L in 24 hours. Going faster risks osmotic demyelination syndrome, a devastating brain injury that can leave you locked-in.

- If you have a salt-wasting syndrome, you may need 4-8 grams of sodium chloride daily-yes, that’s about 1-2 teaspoons of salt, taken under medical supervision.

For hypernatremia:

- Replace water slowly. Use oral fluids if possible. If you’re too sick to drink, IV fluids with low sodium (like 5% dextrose) are used-but never with normal saline.

- Check for infections, fever, or medications that cause dryness.

- Never give concentrated salt solutions unless it’s a life-threatening emergency.

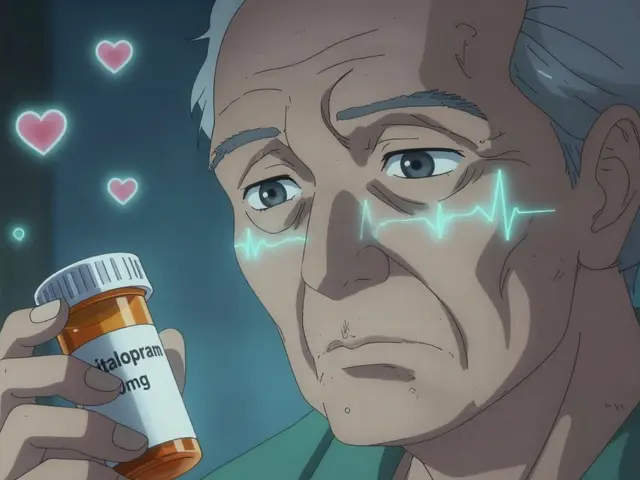

Medications to Avoid

Some drugs that work fine in healthy people are risky in CKD.- Thiazide diuretics (like hydrochlorothiazide): FDA warns against use when GFR is below 30. They’re linked to 25-30% of hyponatremia cases in CKD.

- Vaptans (like tolvaptan): These drugs block vasopressin to help you pee out water. But in advanced CKD, the kidneys don’t respond. The European Medicines Agency restricts their use in stage 4-5 CKD.

- NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen): They reduce kidney blood flow and can worsen sodium imbalance. Avoid them unless absolutely necessary.

The Real Challenge: Managing Multiple Restrictions

CKD patients often face a confusing web of dietary rules: low sodium, low potassium, low protein, fluid limits. Many end up cutting sodium so much that they trigger hyponatremia. A 2020 study found that 22% of hyponatremia cases in late-stage CKD came from patients misunderstanding “low-sodium” as “no sodium.”Education is key. Patients need 3-6 sessions with a renal dietitian to understand what’s safe. Simple tools help: using a measuring cup for fluids, reading labels for sodium content, and knowing which foods are unexpectedly high in salt (like bread, canned soups, or processed meats).

Technology is catching up. In March 2023, the FDA approved a new wearable patch that measures interstitial sodium levels continuously-85% accurate compared to blood tests. It’s not yet standard, but it’s a step toward real-time monitoring without frequent blood draws.

Why This Matters Now

More than 850 million people worldwide have CKD. That number is growing fast-up 29% by 2030. Sodium disorders are responsible for 15-18% of all CKD hospitalizations in the U.S., costing $12,500-$18,000 per episode. In Asia, hyponatremia is even more common, possibly because of stricter dietary advice.But the biggest risk isn’t the numbers-it’s the silence. People don’t realize that fatigue, dizziness, or confusion might be their kidneys failing to manage sodium. And doctors sometimes treat hyponatremia the same way they would in a healthy person-leading to dangerous mistakes.

Dr. Richard Sterns, a leading nephrologist, says the most common error is “failing to recognize the reduced capacity for water excretion.” In other words: your kidneys aren’t broken-they’re overwhelmed. And treating them like they’re still working normally can kill you.

What to Do Next

If you have CKD:- Ask your nephrologist for a serum sodium test at every visit-don’t wait for symptoms.

- Keep a fluid diary: write down everything you drink, even coffee or soup.

- Review all your medications with your pharmacist. Are any of them linked to sodium imbalance?

- See a renal dietitian. Don’t guess what “low sodium” means.

- If you’re over 65 and live alone, ask a family member to help monitor your fluid intake and alert you to early signs like confusion or stumbling.

Sodium disorders in kidney disease aren’t about being perfect. They’re about being aware. Small, smart changes-guided by your care team-can prevent hospital stays, falls, and worse. Your kidneys may be damaged, but you still have control over how you manage what’s left.

Can drinking too much water cause hyponatremia in kidney disease?

Yes. In advanced CKD, the kidneys can’t excrete excess water efficiently. Drinking even a few extra glasses of water in a short time can dilute sodium levels dangerously. That’s why fluid restriction is often part of treatment-especially when GFR is below 30 mL/min/1.73m².

Is low sodium always bad for people with kidney disease?

Not necessarily-but it’s always a sign something’s off. Mild hyponatremia (130-134 mmol/L) is common in CKD and often asymptomatic. But it still raises your risk of falls, fractures, and death. It’s not the low number itself that’s dangerous-it’s what it reveals about your body’s inability to balance fluids.

Can I use salt substitutes if I have CKD?

Be very careful. Most salt substitutes replace sodium chloride with potassium chloride. In CKD, your kidneys can’t clear potassium well, so this can cause dangerous hyperkalemia (high potassium). Always check with your doctor or dietitian before using them.

Why are thiazide diuretics risky in advanced CKD?

Thiazides work in the part of the kidney that stops functioning when GFR falls below 30. They become ineffective at lowering blood pressure and instead cause sodium loss without enough water excretion, leading to hyponatremia. The FDA warns against their use in advanced CKD. Loop diuretics like furosemide are preferred.

Can I still eat salty foods if I have CKD?

It depends. In early CKD, moderate sodium intake (under 2,300 mg/day) is usually safe. In advanced CKD, you may need to limit it to 1,500-2,000 mg/day-but not too low. Over-restricting sodium can reduce your kidney’s ability to excrete water, worsening hyponatremia. Work with a dietitian to find your personal balance.

What are the signs of sodium imbalance I should watch for?

For hyponatremia: nausea, headache, confusion, fatigue, muscle cramps, or stumbling. For hypernatremia: extreme thirst, dry mouth, irritability, restlessness, or drowsiness. If you notice any of these, especially if you’re in late-stage CKD, contact your care team right away. Don’t wait for a lab test.

What’s Next for Patients and Doctors

The 2024 KDIGO guidelines will likely update how we manage sodium in CKD, focusing on personalized fluid targets instead of one-size-fits-all limits. New research is also exploring how the gut helps manage sodium when kidneys fail-opening the door to future treatments that support both organs.For now, the best defense is awareness, regular monitoring, and working with a team that understands the full picture-not just the numbers on a lab report. Your kidneys may be damaged, but your body still has ways to adapt-if you give it the right support.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

14 Comments

Janette Martens December 30, 2025 AT 08:10

so i read this and thought... why the hell are we even talking about sodium like it's a villain? my abuela in quebec used to say "salt is life" and she lived to 98. maybe the real problem is doctors over-medicalizing everything. my cousin with CKD was told to drink less water and eat less salt... then he passed out in the shower. who's really at fault here?

Marie-Pierre Gonzalez December 31, 2025 AT 14:16

Thank you for this comprehensive and deeply thoughtful overview. As a nurse working in nephrology, I see daily how mismanagement of sodium balance leads to preventable hospitalizations. The emphasis on individualized care, especially regarding fluid restriction and diuretic use, is absolutely critical. Please, patients-do not self-prescribe dietary restrictions. Consult your renal dietitian. Your life may depend on it. 💙

Louis Paré January 2, 2026 AT 04:49

Let’s be real. This article reads like a pharmaceutical sales pitch dressed up as medical advice. Thiazides are bad? Vaptans are banned? NSAIDs are evil? Where’s the data on long-term outcomes? Where’s the cost-benefit analysis? Nobody talks about how much money is made off fear-mongering about sodium. It’s all about controlling the patient, not helping them live.

Celia McTighe January 2, 2026 AT 11:32

I have a friend with stage 4 CKD and this post literally saved her life. She was drinking 3L of water a day because she "thought it was healthy" and ended up in the ER with confusion and falls. Now she uses a measuring cup, tracks everything, and checks her sodium every 3 weeks. Small changes. Huge impact. 🙏❤️

Ryan Touhill January 3, 2026 AT 18:49

I must say, the level of intellectual rigor here is... underwhelming. The author cites studies without providing DOI links or journal impact factors. The FDA warnings are mentioned, but not contextualized within the broader regulatory landscape. And where is the discussion of confounding variables in the Japanese solute-restriction study? This feels like a blog post masquerading as clinical guidance.

Teresa Marzo Lostalé January 4, 2026 AT 10:50

I’ve been sitting with this for hours. It’s not just about kidneys. It’s about how we treat our bodies when they’re breaking down. We want quick fixes, but the body doesn’t work like an app. You don’t update your kidneys-you learn to live with them. This post didn’t just inform me. It made me feel seen. 🌿

ANA MARIE VALENZUELA January 4, 2026 AT 12:44

This is the most dangerous misinformation I’ve seen in months. You’re telling people to restrict fluids to 800mL/day? That’s a death sentence for elderly patients. Who authorized this? The FDA doesn’t regulate water intake. And you’re blaming thiazides when the real issue is poor hydration monitoring in nursing homes. This is negligence dressed as advice.

oluwarotimi w alaka January 6, 2026 AT 10:47

this is why africa is better off. we dont have all these fancy doctors telling us what to drink or eat. my uncle had kidney problem and he just drank palm wine and ate yam. he lived 10 years longer than the doctor said he would. you westerners overthink everything. sodium? its just salt. eat it. live.

Debra Cagwin January 7, 2026 AT 00:58

To anyone reading this and feeling overwhelmed: you’re not alone. Start with one thing. Maybe it’s writing down your fluids for a week. Or asking your pharmacist to review your meds. Small steps. No perfection needed. You’re doing better than you think. I believe in you. 💪

Hakim Bachiri January 8, 2026 AT 07:49

I’ve read this three times. And I’m still not convinced. The 2023 Japanese study? Small sample size. The wearable patch? Still in beta. The FDA warning? Misinterpreted. This feels like a cascade of half-truths wrapped in a pretty infographic. And don’t get me started on "renal dietitians"-who certifies them? Are they even MDs? I’m not saying it’s wrong... I’m saying it’s not proven.

Ellen-Cathryn Nash January 9, 2026 AT 10:37

I used to think hyponatremia was just a lab glitch. Then my sister, 72, with CKD, started stumbling in the hallway. We thought it was dementia. Turns out? She was drinking 4 liters of herbal tea a day because "it's detoxing." She spent 11 days in the hospital. They gave her 3% saline slowly. She woke up crying, asking why no one told her water wasn't always good. This article? It’s a lifeline. I’m printing it.

Samantha Hobbs January 9, 2026 AT 12:29

so wait-so if i have ckd and i drink a bottle of water after i pee, am i gonna die? like, literally? this is insane. my mom does that. she’s always chugging water. i need to talk to her. this is too real.

Nicole Beasley January 10, 2026 AT 16:37

Wait so can I still have my morning soup? 😅 I love broth... but now I’m scared to eat anything. Is there a list of safe foods? Or a chart? I’m just trying to survive this without losing my mind.

Julius Hader January 11, 2026 AT 01:20

I’ve been managing CKD for 8 years. This is the first time I’ve read something that didn’t make me feel like a broken machine. You didn’t just list facts-you explained why. And that matters. Thank you. I’m sharing this with my support group.