Health December 1, 2025

Aminoglycoside Antibiotics and Kidney Damage: What You Need to Know About Nephrotoxicity

Aminoglycoside Nephrotoxicity Risk Calculator

Assess Your Risk

When you’re fighting a serious bacterial infection-like sepsis, pneumonia, or a complicated urinary tract infection-doctors sometimes turn to aminoglycoside antibiotics. Drugs like gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin are powerful. They kill bacteria fast. But there’s a dark side: about 1 in 5 people who take them develop kidney damage. It’s not rare. It’s not a fluke. It’s predictable. And it’s avoidable-if you know what to watch for.

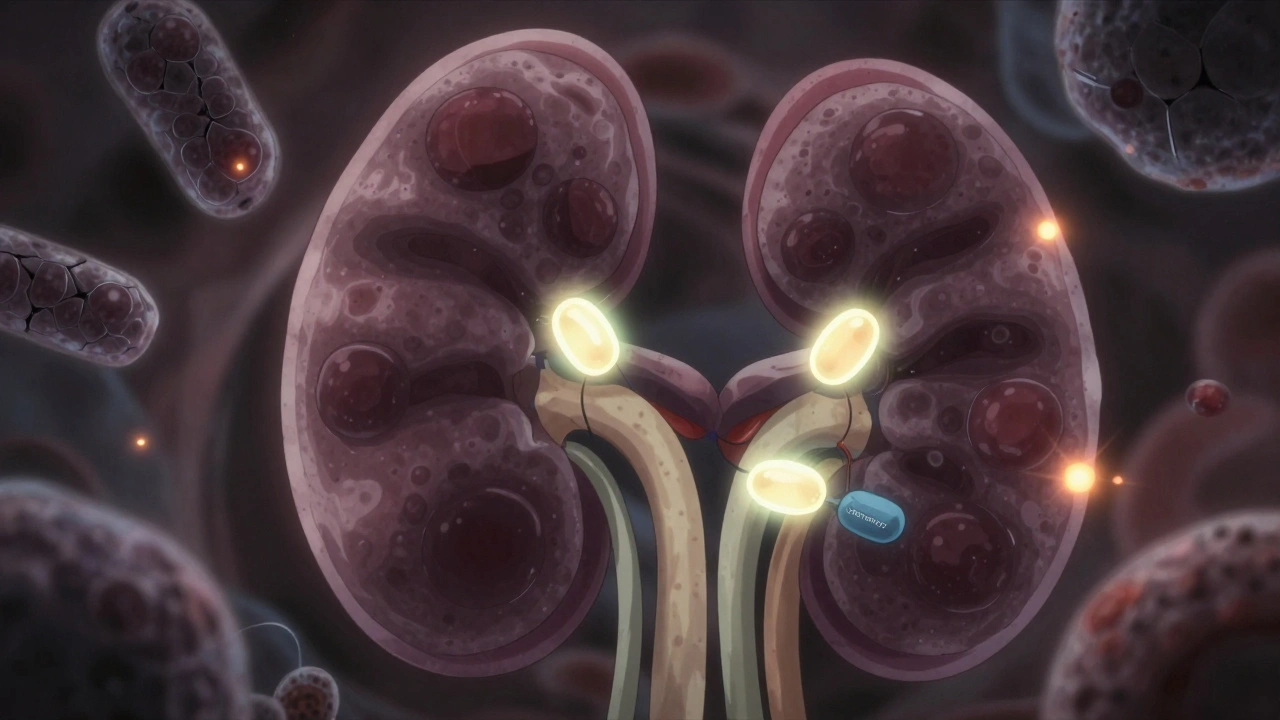

How Aminoglycosides Hurt the Kidneys

These antibiotics don’t just float through your body and disappear. About 5% of every dose gets trapped in the cells lining the proximal tubules of your kidneys. That’s where the trouble starts. These cells are designed to reabsorb nutrients and filter waste, but they accidentally grab onto aminoglycosides like a magnet. Once inside, the drugs pile up in lysosomes-the cell’s recycling centers-and start breaking things down.

It’s not just a clog. It’s a cascade. The buildup triggers oxidative stress, damages mitochondria, and shuts down energy production. Cells swell. Membranes rupture. Myeloid bodies-strange, layered structures made of drug-laden lipids-appear in urine and under the microscope. This isn’t just inflammation. It’s cell death. And it happens quietly, over days, not hours.

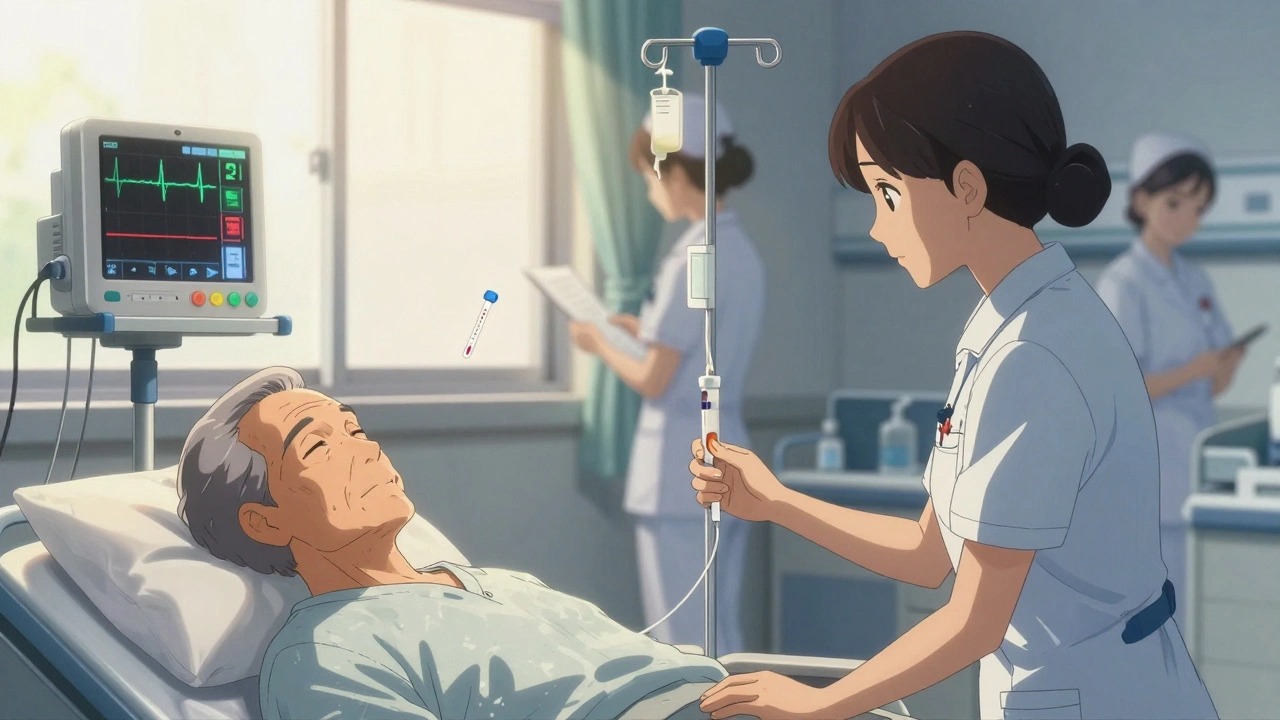

What Nephrotoxicity Looks Like in Real Patients

Most people won’t feel sick right away. There’s no sharp pain. No fever. Instead, your creatinine slowly creeps up. A rise of 0.5 mg/dL or 50% above your baseline is the red flag. Urine output? Usually still normal. That’s why it’s called nonoliguric acute kidney injury-you’re still peeing, but your kidneys aren’t filtering properly.

Early signs show up in urine tests: more sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium leaking out. Proteins like beta-2-microglobulin and enzymes like N-acetylglucosaminidase spike. These aren’t routine tests. But if you’re on aminoglycosides for more than 3 days, your doctor should be checking them.

By day 5 to 7, creatinine levels usually climb. That’s when most cases are caught. And if you’re over 65, already have kidney trouble, or are on another nephrotoxic drug like vancomycin? Your risk jumps 2.7 to 3.2 times higher.

Why Once-Daily Dosing Makes a Difference

For decades, doctors gave aminoglycosides three times a day. It made sense-keep the blood level high. But here’s the twist: giving the full daily dose all at once-once-daily dosing-actually reduces kidney damage.

Why? Because the kidney cells get a break. High, steady drug levels keep them constantly soaked. A single large dose lets the kidneys clear most of the drug between doses. The cells recover. The drug still kills bacteria effectively-because it’s bactericidal and works best in high peaks. But it doesn’t linger in the tubules as long.

Studies show once-daily dosing cuts nephrotoxicity by up to 40%. That’s not a small win. It’s life-changing. And it’s now the standard in the UK, the US, and across Europe.

Timing Matters More Than You Think

Here’s something even stranger: when you take the drug matters. Research found that giving aminoglycosides at 1:30 p.m. led to the lowest risk of kidney damage. Why? Your kidneys have a daily rhythm. Blood flow, filtration rates, and even cellular repair cycles shift with your circadian clock. Giving the drug when kidney function is naturally higher reduces exposure to vulnerable cells.

This isn’t theory. It’s measurable. And while most hospitals don’t yet schedule doses this precisely, it’s a clue that we’re still underestimating how biology interacts with medicine.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

- Age over 65: Kidneys naturally lose function with age. Less reserve means less tolerance.

- Pre-existing kidney disease: If your eGFR is below 60 mL/min/1.73m², your risk triples.

- Vancomycin combo: This pair is a double hit. Together, they cause damage faster and worse than either alone.

- Dehydration: Low blood volume means less kidney flow, more drug concentration in tubules.

- Longer treatment: Beyond 7 days, risk climbs steadily. Every extra day adds up.

These aren’t just statistics. They’re real people. An elderly patient with pneumonia. A diabetic with a foot infection. A cancer patient with a fever after chemo. All of them need antibiotics. But none of them need to lose kidney function because the treatment wasn’t optimized.

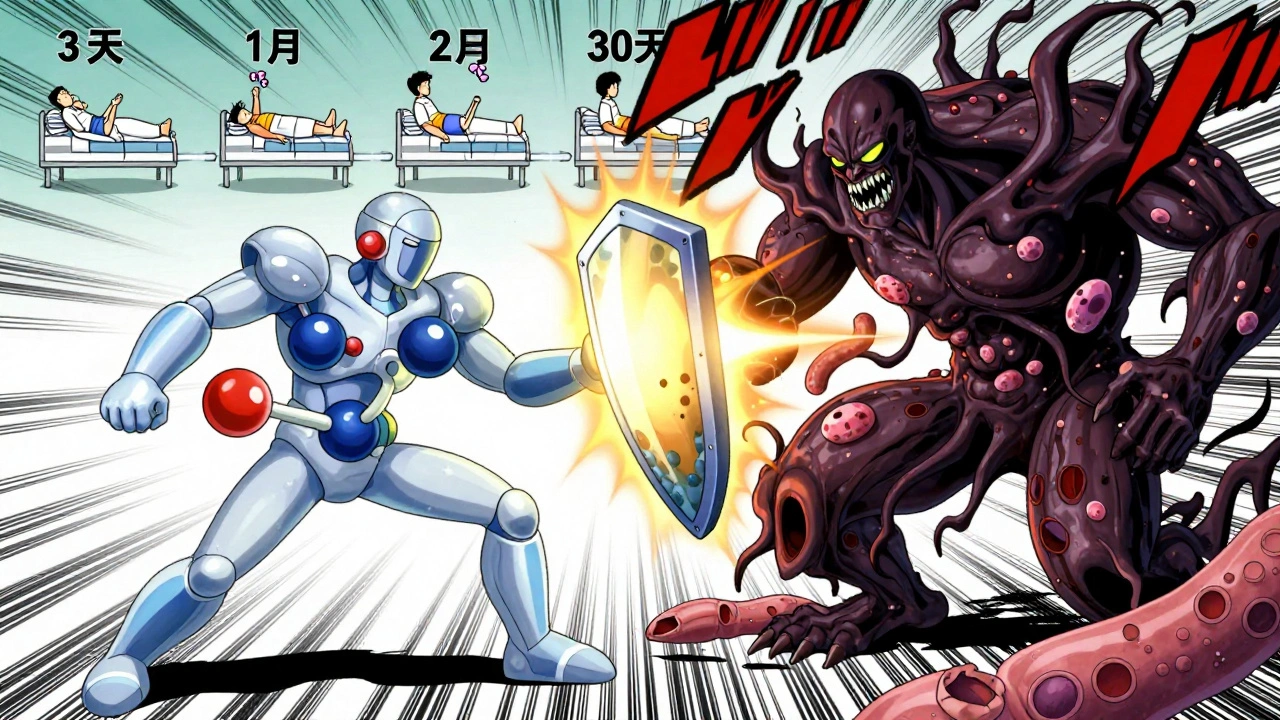

Recovery: Can Your Kidneys Heal?

Good news: in most cases, yes. Once you stop the drug, kidney function usually starts to bounce back in 3 to 5 days. Full recovery often takes 1 to 3 weeks. A 2021 study of over 1,200 patients found that 82% recovered partial or full kidney function within 30 days of stopping aminoglycosides.

But not everyone. About 1 in 5 end up with permanent damage. That’s why prevention isn’t optional-it’s essential. The kidneys can regenerate, but only if the damage isn’t too deep. And if you’re on these drugs for more than 10 days? The risk of irreversible injury rises sharply.

What’s Being Done to Fix This?

Doctors aren’t sitting still. Researchers are racing to find ways to block the damage without weakening the drug’s power. One promising compound? Polyaspartic acid. In lab studies, it stops aminoglycosides from sticking to kidney cells. It blocks the binding to phospholipids. It prevents those toxic myeloid bodies from forming. In animals, it nearly eliminated kidney damage-without reducing antibacterial effect.

So why isn’t it in hospitals yet? Because human trials are slow. A modified version is now in Phase II trials across six U.S. medical centers. It’s not approved. But it’s coming.

Meanwhile, guidelines from the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (2023) say: stick to once-daily dosing, keep trough levels below 1 μg/mL for gentamicin, avoid other kidney drugs if possible, and check creatinine every 48 to 72 hours.

Why We Still Use These Dangerous Drugs

It’s a paradox. These antibiotics are toxic. But they’re also irreplaceable. For multidrug-resistant infections-like those caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Acinetobacter baumannii-there are few alternatives. In sepsis, minutes matter. Aminoglycosides kill fast. They’re cheap. They’re effective.

Over 12 million treatment courses are given worldwide every year. That’s millions of people who need them. And for many, the risk of dying from the infection is far greater than the risk of kidney damage.

But that doesn’t mean we accept the damage. It means we manage it. We dose smarter. We monitor closer. We watch for early signs. We stop before it’s too late.

What Patients and Families Should Ask

- “Is an aminoglycoside absolutely necessary here?”

- “Are we using once-daily dosing?”

- “What’s my baseline creatinine? Are we checking it every two days?”

- “Am I on any other drugs that hurt the kidneys?”

- “If my creatinine rises, what happens next?”

These aren’t hard questions. They’re smart ones. And asking them could mean the difference between recovery and permanent kidney loss.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

11 Comments

Saket Modi December 2, 2025 AT 03:37

bro this is why i hate hospitals. they give you poison and call it medicine 😩

John Biesecker December 3, 2025 AT 04:00

sooo... we're basically saying the body's like a sponge for toxic junk and the only way to not drown is to give it all at once? 🤯 kinda wild that we've been doing it wrong for decades. also why is 1:30 pm the magic hour? is the kidney on a coffee break then?

Genesis Rubi December 3, 2025 AT 05:04

this is why america needs to stop trusting european medical advice. we have better tech here. why are we following some UK guideline like it's gospel? 🇺🇸

Doug Hawk December 4, 2025 AT 15:59

the lysosomal accumulation mechanism is fascinating but underappreciated. the proximal tubule cells express megalin receptors that internalize aminoglycoside-phospholipid complexes via endocytosis-once internalized, the drug disrupts mitochondrial membrane potential and triggers caspase-independent apoptosis. what's wild is that this isn't dose-dependent in a linear way, it's threshold-based. the 5% retention rate? that's the tipping point. and the circadian rhythm angle? that's the real breakthrough. renal perfusion peaks around mid-afternoon, so timing the bolus to coincide with peak GFR reduces tubular exposure time. this isn't just dosing-it's chronopharmacology.

John Morrow December 6, 2025 AT 06:54

let's be real-this is just another example of how pharmaceutical companies prioritize profit over patient safety. they knew about the nephrotoxicity for 40 years. they didn't change the protocol because three-times-daily dosing meant more prescriptions, more billing, more revenue. now they're 'discovering' once-daily? please. it's a rebrand. and polyaspartic acid? it's not a cure-it's a band-aid on a bullet wound. the real problem is that we treat antibiotics like magic bullets and ignore the collateral damage.

Kristen Yates December 6, 2025 AT 23:26

i work in a hospital pharmacy and i see this every day. elderly patients on vancomycin + gentamicin. no one checks their creatinine until day 5. i wish more families asked the questions in that last section. it's scary how passive people are about their own health.

Michael Campbell December 7, 2025 AT 19:38

they're hiding the truth. this is all part of the medical-industrial complex. the government knows aminoglycosides cause kidney failure but keeps pushing them because they're cheap. who benefits? big pharma. who pays? the poor. it's genocide by protocol.

Saravanan Sathyanandha December 8, 2025 AT 09:20

as someone from India where antibiotics are often sold over the counter without prescription, this article is a lifeline. many patients here self-medicate with gentamicin for fever or cough. they don't know it can wreck their kidneys. we need public health campaigns-not just for doctors, but for families. this isn't just science, it's survival.

alaa ismail December 8, 2025 AT 16:23

honestly i had no idea this was a thing. i thought antibiotics were just... antibiotics. thanks for breaking it down without making me feel dumb.

ruiqing Jane December 9, 2025 AT 01:09

this is why we need more nurses and pharmacists involved in antibiotic stewardship. the doctors are overloaded, but the people who actually handle the meds? they see the patterns. if you're on aminoglycosides, ask for a daily creatinine check. it takes 5 minutes. it could save your kidneys.

Fern Marder December 9, 2025 AT 15:42

polyaspartic acid sounds too good to be true. i’ve seen too many ‘miracle’ compounds fail in phase III. but hey, if it works? i’ll be the first to say i was wrong. 🤞