Health February 13, 2026

Drug-Induced Liver Injury: High-Risk Medications and How to Monitor Them

Every year, thousands of people end up in the hospital not because of a virus or a bad diet, but because of something they took to feel better. Medications meant to treat infections, pain, or chronic conditions can sometimes damage the liver - a silent, slow-burning problem that often goes unnoticed until it’s too late. This is called drug-induced liver injury (DILI), and it’s one of the most underrecognized causes of liver failure in the U.S. and the U.K.

What Is Drug-Induced Liver Injury?

DILI happens when a drug, supplement, or herbal product harms the liver. It’s not the same as alcohol-related liver damage or fatty liver disease. This is a direct reaction to something you swallowed. The liver is especially vulnerable because it’s the body’s main filter - it breaks down nearly every medication you take. But sometimes, the process of breaking things down creates toxic byproducts that attack liver cells.

There are two main types. The first is intrinsic DILI - predictable, dose-dependent, and usually happens when you take too much. Think acetaminophen (Tylenol). The second is idiosyncratic DILI - unpredictable, rare, and not tied to dosage. It can strike anyone, even at normal doses. This type makes up about 75% of all cases and is the hardest to spot.

The Most Dangerous Medications

Not all drugs carry the same risk. Some are far more likely to cause liver damage than others. Here’s what the data shows:

- Acetaminophen - The number one cause of acute liver failure in the U.S., responsible for nearly half (45.8%) of all cases. A single dose over 7-10 grams can be deadly. Even at normal doses, people with liver disease or who drink alcohol are at higher risk.

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin) - The most common cause of idiosyncratic DILI. It’s a widely prescribed antibiotic, but it can trigger liver injury in 1 out of every 2,000 to 10,000 courses. Symptoms often show up weeks after starting it - yellow skin, dark urine, intense itching.

- Valproic acid - Used for seizures and mood disorders. It can cause severe liver damage, especially in children under two. Fatality rates in severe cases hit 10-20%.

- Isoniazid - A tuberculosis drug. About 1% of people on it develop liver injury, but the risk jumps to 2-3% if you’re over 35. Many patients don’t feel anything until their ALT levels spike to over 1,000 (normal is under 40).

- Antiepileptic drugs like carbamazepine and phenytoin - Linked to immune-mediated liver damage. Symptoms can mimic hepatitis.

- Herbal and dietary supplements - Once a small fraction of cases, now make up 20% of DILI reports in the U.S. Products with green tea extract, kava, anabolic steroids, and weight-loss formulas are top offenders. Men are more likely to get DILI from supplements than women.

Statins, often blamed for liver problems, rarely cause serious injury. Less than 1 in 100,000 users develop severe damage. Mild ALT elevations are common but harmless. The real danger comes from combinations - like taking statins with antibiotics or supplements.

How to Spot DILI Early

Most people don’t feel anything until their liver is badly damaged. That’s why symptoms often show up too late. But there are warning signs:

- Yellowing of the skin or eyes (jaundice)

- Dark urine

- Extreme fatigue

- Nausea or vomiting

- Itching without a rash

- Abdominal pain, especially on the right side

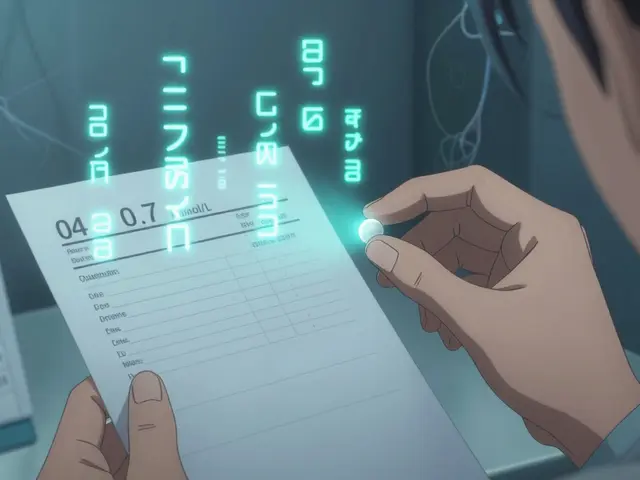

Doctors use blood tests to confirm liver injury. Two key numbers matter:

- ALT (alanine aminotransferase) - If it’s more than 3 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), it signals liver cell damage.

- ALP (alkaline phosphatase) - If it’s over 2x ULN, it suggests bile flow is blocked - a cholestatic pattern.

Hy’s Law is a critical rule of thumb: if both ALT (or AST) is over 3x ULN and total bilirubin is over 2x ULN, there’s a 10-50% chance of acute liver failure. This combination should trigger immediate action.

Who Needs Monitoring?

You don’t need routine liver tests for every medication. But for high-risk drugs, monitoring saves lives.

- Isoniazid (for TB) - Get liver tests before starting, then every month for the first 3 months. Stop the drug if ALT rises above 3-5x ULN or if symptoms appear.

- Valproic acid - Check liver enzymes before starting, then at 1, 3, and 6 months. More frequent if you’re under 2, on multiple seizure meds, or have a metabolic disorder.

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate - No routine testing needed, but if you’re over 65, have liver disease, or are on other liver-affecting drugs, ask your doctor about a baseline test.

- Statins - Routine monitoring isn’t recommended. The risk is too low. But if you feel unusually tired or notice jaundice, get tested.

The American College of Gastroenterology says: “If you’re taking more than five medications, your risk of DILI goes up. Talk to your pharmacist.” Pharmacists are often the first to catch dangerous interactions. One patient in Bristol avoided liver failure when her pharmacist spotted a conflict between her seizure drug and a new antibiotic before she even took it.

What Happens After Diagnosis?

The single most important step? Stop the drug. In 90% of cases, liver enzymes start to drop within 1-2 weeks after stopping the culprit. Recovery takes time - most people feel better in 3-6 months. But 12% of patients have permanent damage.

For acetaminophen overdose, time is everything. If you take N-acetylcysteine (NAC) within 8 hours, it prevents liver failure almost 100% of the time. After 16 hours, effectiveness drops to 40%. If you suspect an overdose, don’t wait. Go to the ER.

There’s no magic antidote for other types of DILI. Supportive care - rest, fluids, avoiding alcohol - is the main treatment. In severe cases, a liver transplant may be needed. DILI causes about 13% of all liver transplants in the U.S., according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

New Tools and Future Hope

Science is catching up. Researchers now use genetic testing to find people at risk. For example, people with the HLA-B*57:01 gene are 80 times more likely to get liver damage from flucloxacillin. Testing for this before prescribing can prevent injury.

Another breakthrough is the DILI-similarity score - a tool that analyzes a drug’s chemical structure to predict liver risk with 82% accuracy. It’s helping drug companies design safer medicines.

Future blood tests might detect liver injury before ALT rises. MicroRNA-122, a biomarker released by dying liver cells, spikes 12-24 hours before ALT. This could allow doctors to act before serious damage occurs.

Electronic health records are also being upgraded. Hospitals in the U.S. are now using alerts that pop up when a doctor prescribes two high-risk drugs together. Early data shows this could prevent 15-20% of severe DILI cases.

What You Can Do

- Always tell your doctor and pharmacist about every medication, supplement, and herbal product you take - even “natural” ones.

- Don’t assume supplements are safe. Green tea extract, kava, and weight-loss pills have caused serious liver injury.

- If you’re on a high-risk drug, know the warning signs. Don’t wait for jaundice to appear.

- Never take more than 3 grams of acetaminophen a day. If you’re over 65 or have liver disease, stick to 2 grams.

- If you feel unwell while on a new medication, get your liver checked. It’s simple, fast, and could save your life.

DILI isn’t common, but when it happens, it can be devastating. The good news? Most cases are preventable. With awareness, simple blood tests, and honest conversations with your care team, you can stay safe while taking the medicines you need.

Can over-the-counter supplements cause liver damage?

Yes. Herbal and dietary supplements are now responsible for about 20% of all drug-induced liver injury cases in the U.S. Products containing green tea extract, kava, anabolic steroids, and weight-loss formulas have been linked to severe liver damage. Unlike prescription drugs, supplements aren’t tested for safety before they’re sold. Many people assume they’re harmless, but they can be just as dangerous - or more - than medications.

Is liver damage from drugs always reversible?

In most cases, yes - if caught early. Stopping the drug leads to recovery in about 90% of patients within 1-2 weeks. Full recovery can take 3-6 months. But in 12% of cases, the damage is permanent, leading to chronic liver disease or cirrhosis. A small percentage require a liver transplant. The key is early detection and stopping the medication immediately.

Why do some people get DILI and others don’t?

It’s mostly genetic and metabolic. Idiosyncratic DILI - the unpredictable kind - happens because of how your body processes drugs. Some people have genetic variations that make their liver enzymes produce more toxic byproducts. Others have immune systems that mistakenly attack liver cells after drug exposure. Age, gender, alcohol use, and existing liver disease also play a role. Women and older adults are at higher risk overall.

Do I need regular liver tests if I take statins?

No. Routine liver testing for statin users isn’t recommended by major medical groups. Severe liver injury from statins is extremely rare - about 1-2 cases per 100,000 patient-years. Mild ALT elevations are common but harmless. Instead of testing, watch for symptoms: yellow skin, dark urine, extreme fatigue. If they appear, get tested. Don’t stop your statin without talking to your doctor.

What should I do if I think a medication is hurting my liver?

Stop taking the medication immediately and contact your doctor. Don’t wait for symptoms to worsen. Get a blood test to check your liver enzymes (ALT, AST, ALP, bilirubin). If you’re on a high-risk drug like isoniazid or valproic acid, your doctor may need to switch you to a safer alternative. If you’ve taken too much acetaminophen, go to the ER - even if you feel fine. Time matters.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

12 Comments

Charlotte Dacre February 15, 2026 AT 06:44

So let me get this straight - we’re told to avoid supplements because they’re ‘natural’ but then we’re handed a 12-page medical textbook on which exact herbal extract will turn your liver into a charcoal briquette? I took ashwagandha for ‘stress’ and now I’m Googling ‘liver transplant waiting lists’ like it’s a Spotify playlist. Thanks, Big Wellness.

Betty Kirby February 15, 2026 AT 20:42

The fact that people still think ‘natural’ means ‘safe’ is why we have a public health crisis wrapped in a yoga mat. Green tea extract? It’s not a tea. It’s a concentrated solvent for hepatocytes. If you’re taking it to ‘detox,’ you’re detoxing your liver.

Josiah Demara February 16, 2026 AT 20:20

You people are missing the real issue. The article mentions Hy’s Law but doesn’t explain that it’s been outdated since 2018. The new threshold is ALT > 5x ULN with bilirubin > 1.8x ULN. Also, amoxicillin-clavulanate isn’t the #1 cause of idiosyncratic DILI - it’s minocycline. The CDC updated the guidelines in January. You’re all operating on 2015 data. And don’t get me started on how they mischaracterized statins. The real risk is polypharmacy in patients over 65 with CKD. This article is a glorified blog post with footnotes.

Kaye Alcaraz February 18, 2026 AT 19:10

This is the kind of clarity we need. No fluff. Just facts. If you’re on isoniazid, get tested. If you’re taking kombucha with a side of turmeric and ashwagandha, get tested. Your liver doesn’t care if it’s ‘organic.’ It just wants to live. Thank you for writing this. Share it with your aunt who thinks ‘detox tea’ is a vitamin.

Sarah Barrett February 19, 2026 AT 17:05

I work in urgent care. Last month, a 58-year-old woman came in with jaundice, no fever, no pain. She’d been taking ‘LiverCleanse™’ for three weeks. Her ALT was 2800. She didn’t think it was a problem because it was ‘herbal.’ We had to admit her. She’s on the transplant list now. This isn’t theoretical. It’s Tuesday.

Erica Banatao Darilag February 21, 2026 AT 12:32

i just want to say thank you for this post. i’ve been taking valproic acid for 12 years and never knew about the monitoring schedule. my dr never told me. i’m gonna call them tomorrow and ask for the tests. i’m so glad i read this. really important stuff.

Mike Hammer February 22, 2026 AT 18:12

I’ve been on statins for 7 years. My ALT was 45 last year. My doctor said ‘meh.’ I’m still here. Still driving. Still eating pizza. The real danger isn’t the statin. It’s the fear-mongering. Chill out. Your liver’s tougher than you think.

Daniel Dover February 23, 2026 AT 18:30

Stop taking supplements. Get bloodwork. If you’re on more than 5 meds, talk to a pharmacist. Done.

Joe Grushkin February 24, 2026 AT 16:27

Let me guess - you’re one of those people who thinks ‘liver injury’ is a metaphor for bad life choices. The liver doesn’t care if you’re ‘spiritual’ or ‘woke.’ It just processes toxins. If you’re using ‘natural remedies’ to replace insulin or blood pressure meds, you’re not healing. You’re playing Russian roulette with your organs. This isn’t a wellness trend. It’s a death sentence with a yoga pose.

Michael Page February 26, 2026 AT 00:26

The real tragedy isn’t the drugs. It’s the silence. We’re taught to trust science, but then we’re left alone with a bottle of pills and no one to ask, ‘Is this safe?’ The system doesn’t warn us. It just waits. And by the time we feel it - it’s too late. We’re not patients. We’re experiments with a heartbeat.

Mandeep Singh February 27, 2026 AT 14:11

I have been researching this for 18 months. In India, DILI from ayurvedic products is the leading cause of acute liver failure in young adults. Over 60% of cases are from unregulated herbal formulations sold online. The Indian government has no mandatory reporting system. The WHO doesn’t track it. And yet, you Americans are shocked that ‘green tea extract’ caused a problem? We’ve been drowning in this for decades. Your ‘natural’ supplements are our unregulated poison. You’re not pioneers. You’re latecomers to a global disaster.

Esha Pathak March 1, 2026 AT 01:00

i think about how our bodies are just… machines. we take pills like they’re candy. we don’t think about the chemical dance happening inside. the liver doesn’t have a voice. it just keeps working until it breaks. and then we say ‘oh i didn’t know’ like we didn’t know the sun burns skin. we’re not careless. we’re disconnected. this post? it’s a mirror. look at it. really look.