Health January 19, 2026

Insulin Biosimilars: What You Need to Know About Cost, Safety, and Market Options

Diabetes affects over 500 million people worldwide. For many, insulin isn’t just medicine-it’s survival. But the price of branded insulin can be crushing. In the U.S., some patients pay over $400 a month for a single vial. That’s why insulin biosimilars have become a lifeline for millions. They’re not generics. They’re not copies. They’re highly similar versions of complex biological insulin products, proven safe and effective through years of testing. And they’re changing how diabetes is treated around the world.

What Makes Insulin Biosimilars Different from Generics?

When you think of a generic drug, you imagine a small, identical pill made of the same chemical as the brand name. That’s not how insulin works. Insulin is a protein made by living cells-bacteria or yeast engineered to produce human insulin. No two batches are exactly alike, even from the same manufacturer. That’s why insulin biosimilars can’t be called generics.

A generic aspirin has the same molecule as Bayer’s. A biosimilar insulin has the same structure, function, and effect-but it’s made using a different cell line, fermentation process, or purification method. Think of it like two hand-crafted wooden chairs that look and feel the same, but were built in different workshops. The result? The same support, just a different build.

To get approved, insulin biosimilars must pass strict tests: chemical analysis, animal studies, and clinical trials showing no meaningful difference in blood sugar control, safety, or side effects compared to the original. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) both require this. But here’s the catch: the FDA requires an extra step for a product to be labeled “interchangeable”-meaning a pharmacist can swap it for the brand without a doctor’s OK. Only a few insulin biosimilars have that status in the U.S. In Europe, approval means interchangeability by default.

How Much Do Insulin Biosimilars Save?

Cost is the biggest driver behind insulin biosimilars. In 2025, the average price for a branded long-acting insulin like Lantus was $280 per vial in the U.S. The biosimilar version, Basaglar, sold for $150. That’s a 46% drop. Semglee, another biosimilar to Lantus, dropped even lower-around $90 per vial after rebates and insurance.

For patients paying out-of-pocket, that’s life-changing. One user on the American Diabetes Association forum shared: “Switched to Basaglar. My A1C dropped from 7.8 to 7.2. My monthly cost went from $450 to $90.” That’s not a fluke. Studies show insulin biosimilars cut costs by 15% to 30% compared to the original. In India, where 141 million people have diabetes, some biosimilars cost 70% less than branded versions. That’s why adoption there is growing fast.

The U.S. government is helping too. Medicare now reimburses pharmacies at the biosimilar’s average selling price (ASP) plus 8%, making it profitable for pharmacies to stock them. That’s pushing more options into pharmacies and mail-order services.

Market Leaders and Key Products

There are six insulin biosimilars approved in the European Union and five in the U.S. as of early 2026. The big names behind them are companies you might not know-Biocon, Samsung Bioepis, BGP Pharma-but their products are in clinics from London to Lagos.

- Semglee (insulin glargine-yfgn): Biosimilar to Lantus. Marketed by Viatris and Biocon. Approved in the U.S. as interchangeable in 2021. Now the most prescribed biosimilar insulin in America.

- Basaglar (insulin glargine): Biosimilar to Lantus. Launched by Eli Lilly in 2016. Still holds a big share, even after Semglee entered.

- Admelog (insulin lispro): Biosimilar to Humalog. Used for mealtime insulin. Cheaper than the original, but not interchangeable in the U.S.

- Hygeia (insulin aspart): A newer biosimilar to NovoRapid, approved in Europe and Australia.

- Insulin glulisine biosimilar: Recently approved in Europe, targeting Apidra.

Sanofi, the maker of Lantus, responded to biosimilar competition by offering its own “unbranded” version of Lantus at a lower price. It’s not a biosimilar-it’s the same product, just sold without the brand name. It’s a smart move: they keep market share while undercutting biosimilars on price.

Why Isn’t Everyone Switching?

Despite the savings, insulin biosimilars still make up less than 30% of the insulin market in the U.S. Why? Three big reasons: fear, confusion, and policy.

First, fear. Many patients and doctors worry that switching insulin-even to something proven equivalent-could cause blood sugar swings. One Reddit user wrote: “My doctor switched me to a biosimilar without warning. I had more lows. Switched back after two weeks.” That’s rare, but it happens. Most cases involve dosing adjustments, not safety failures.

Second, confusion. The difference between “biosimilar” and “interchangeable” isn’t clear to patients or even some pharmacists. In 17 states, pharmacists can’t swap insulin biosimilars without a doctor’s permission. In others, they can. That creates a patchwork system that slows adoption.

Third, inertia. Doctors have been prescribing Lantus or Humalog for 20 years. They know how it works. They know how patients respond. Switching feels risky-even when the science says it’s not.

But data tells a different story. A 2025 survey found 68% of patients who switched to biosimilars saw no change in effectiveness or side effects. Another 22% needed a small dose tweak-usually within the first month. Only 10% had to switch back.

How to Switch Safely

If you’re considering switching from a branded insulin to a biosimilar, don’t just ask your pharmacist. Talk to your endocrinologist or diabetes educator. Here’s what works:

- Start with a clear plan. Don’t switch cold turkey. Your doctor should decide which biosimilar matches your current insulin type-long-acting, rapid-acting, etc.

- Monitor closely. Check your blood sugar more often for the first 4 to 6 weeks. Keep a log. Note any unusual highs or lows.

- Adjust if needed. Some patients need a 5-10% dose change when switching. That’s normal. It’s not a failure-it’s fine-tuning.

- Know your rights. In the U.S., check if your state allows pharmacist substitution. If not, your prescription must specify “dispense as written.”

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends a 3-6 month transition period with regular follow-ups. That’s not because biosimilars are unsafe-it’s because every body reacts differently to insulin. The goal is to find the right dose, not to panic over a single high reading.

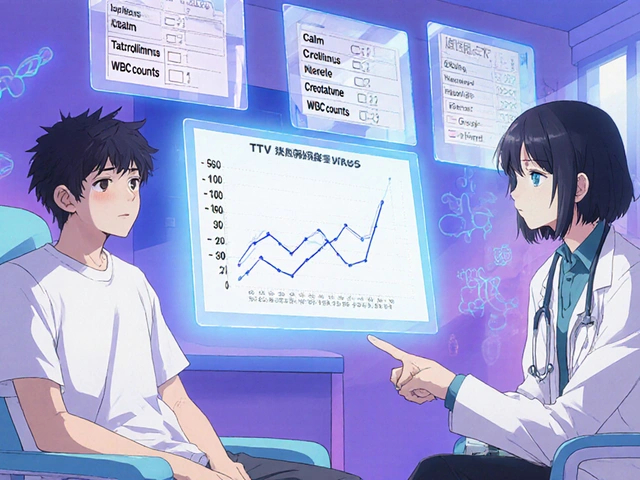

Global Trends and What’s Next

The U.S. holds nearly 30% of the global insulin biosimilar market, but growth is fastest in Asia. India and China are investing heavily in biosimilar production. By 2030, experts predict insulin biosimilars will make up 60-65% of insulin use in emerging markets.

Europe is ahead of the U.S. in adoption. Germany, France, and the UK have strong public health policies that favor biosimilars. In Germany, insulin biosimilars already hold over 50% of the market.

What’s coming next? Biosimilars for newer insulins like Toujeo (insulin glargine U300) and Tresiba (insulin degludec). These are currently protected by patents, but those expire between 2026 and 2028. Once they do, prices could drop even further.

Manufacturers are also working on smart pens and connected devices that pair with biosimilar insulins. Seventy-eight percent of companies are investing in these next-gen delivery systems. That means better dosing accuracy, fewer errors, and more confidence for patients.

The Bottom Line

Insulin biosimilars aren’t a gimmick. They’re not a compromise. They’re science-backed, cost-saving alternatives that work just as well as the originals. For people who can’t afford $400 insulin, they’re not optional-they’re essential.

Yes, switching takes planning. Yes, some people need minor adjustments. But the evidence is clear: biosimilars save lives and money. The biggest barrier isn’t science-it’s perception. And that’s changing.

If you’re on insulin and paying too much, ask your doctor: “Is there a biosimilar option for me?” Don’t wait for your pharmacy to suggest it. Be proactive. Your health-and your wallet-will thank you.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

11 Comments

clifford hoang January 19, 2026 AT 11:32

So let me get this straight... Big Pharma lets a few companies make "similar" insulin, but only if they jump through 17 bureaucratic hoops? 🤔 Meanwhile, the same corporations patent the original formula for 20 years and charge $400/vial like it's liquid gold. This isn't science-it's a rigged game. And don't even get me started on "interchangeable"-that's just a fancy word for "we'll let you swap it unless you have a bad day and your blood sugar spikes." 💸💉 #ConspiracyTheoryApproved

Nadia Watson January 20, 2026 AT 14:12

I just want to say thank you for writing this with such care. As someone who’s been on insulin for 18 years, I’ve seen the fear people have around switching-even when the data says it’s safe. My niece started on Semglee last year, and her A1C improved. She’s now able to afford her meter strips too. Small wins matter. 🙏

Jacob Cathro January 21, 2026 AT 04:50

Biosimilars? More like bioslumbers. 😴 All this talk about "equivalent" but nobody’s talking about the fact that the cell lines are different, so the glycosylation profiles vary. You think your body doesn’t notice? Bro, your immune system is not dumb. And don’t even get me started on the "interchangeable" label-FDA’s just trying to make it look like they’re doing something. It’s all corporate theater. #PharmaShenanigans

Paul Barnes January 22, 2026 AT 23:43

The clinical data supporting insulin biosimilars is robust. Multiple randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and post-marketing surveillance studies confirm non-inferiority in glycemic control and safety profiles. The notion that biosimilars are somehow inferior is scientifically unfounded.

kumar kc January 23, 2026 AT 05:04

India makes it cheap. USA makes it expensive. Why? Because profit > people.

Thomas Varner January 24, 2026 AT 23:36

I switched to Basaglar last year… and honestly? I didn’t notice a difference. Not a single one. My glucose trends were identical, my lows didn’t increase, my insurance paid half… but my doctor? She acted like I was doing something dangerous. Like I’d somehow broken a sacred rule. It’s not the insulin that’s scary-it’s the fear they’ve sold us for decades. 🤷♂️

Art Gar January 26, 2026 AT 08:38

While cost reduction is commendable, one must not conflate economic accessibility with therapeutic equivalence. The regulatory frameworks in the U.S. and E.U. differ substantially in their criteria for interchangeability, and this disparity must be acknowledged before widespread adoption is encouraged.

thomas wall January 27, 2026 AT 22:05

The European model-where biosimilars are automatically interchangeable-is not only pragmatic, it is morally superior. The U.S. system, by contrast, is a labyrinth of patent thickets, pharmacy restrictions, and physician inertia. We are not saving lives-we are preserving profits under the guise of caution.

Shane McGriff January 29, 2026 AT 17:34

If you're thinking about switching, don't panic. Talk to your care team. Track your numbers. Give it 4-6 weeks. Most people do fine. I’ve helped over 50 patients switch-only two needed adjustments beyond 10%, and both were on very sensitive regimens. You’re not risking your health-you’re reclaiming your budget. And that’s powerful.

sagar sanadi January 30, 2026 AT 16:03

So now the big pharma companies are selling their own "unbranded" insulin? Hah. That’s like McDonald’s selling a burger without the logo… but still charging $12. "Oh no, we’re not the same company anymore!" 🤡

Courtney Carra February 1, 2026 AT 15:05

It’s wild how we treat insulin like it’s some fragile magic potion… when it’s literally just a protein. 🤯 We’ve been conditioned to fear change-even when the science says it’s safe. Maybe we’re not afraid of the biosimilar… maybe we’re afraid of admitting how broken the system is. And that’s the real insulin crisis.