Health December 8, 2025

Therapeutic Equivalence Codes (TE Codes) Explained: How Generic Drugs Are Approved and Substituted

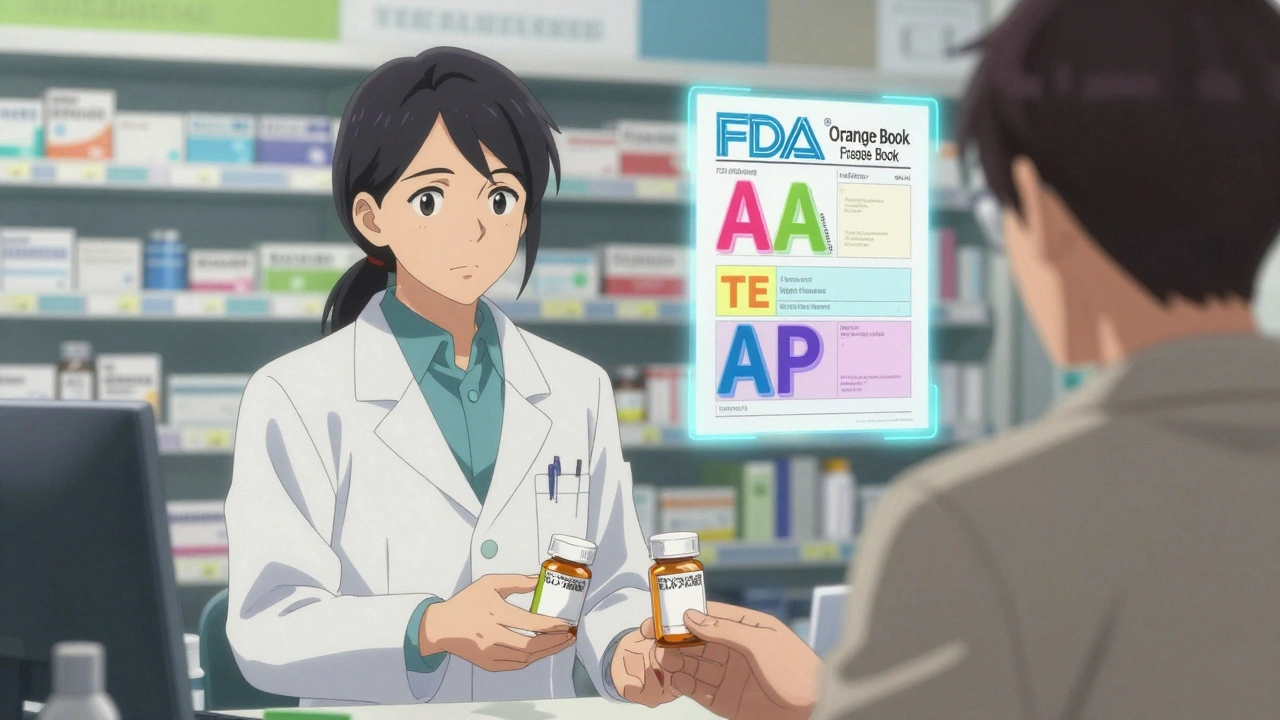

When you pick up a prescription for a generic drug, you might assume it’s just a cheaper version of the brand-name pill. But here’s the truth: not all generics are created equal. That’s where Therapeutic Equivalence Codes come in. These simple two- or three-letter codes-like AA, AP, or AT-are the FDA’s official stamp of approval that a generic drug can be safely swapped for its brand-name counterpart without any loss in effectiveness or safety. If you’ve ever wondered why your pharmacist hands you a different-looking pill with the same name, or why your insurance pushes for generics, this is the system behind it.

What Are Therapeutic Equivalence Codes (TE Codes)?

Therapeutic Equivalence Codes are part of the FDA’s Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, commonly known as the Orange Book. First introduced in 1984 after the Hatch-Waxman Act, these codes were created to bring clarity to a messy system. Before TE Codes, pharmacists had no consistent way to know if a generic drug would work just as well as the brand. Some states allowed substitution, others didn’t. Patients got mixed results. The FDA stepped in to create a science-based standard.

Every multi-source drug-meaning any medicine with more than one manufacturer-gets a TE Code if it’s been reviewed and approved by the FDA. The code tells you two things: whether the drug is equivalent (A or B), and how it was evaluated (the second or third letter). An 'A' means it’s therapeutically equivalent. A 'B' means it’s not. That’s it. Simple. But the details behind it? That’s where the science gets deep.

How the FDA Decides If a Generic Is Equivalent

The FDA doesn’t just look at the active ingredient. They check three things: pharmaceutical equivalence, bioequivalence, and clinical equivalence.

First, pharmaceutical equivalence. That means the generic has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. If your brand is a 20mg tablet taken by mouth, the generic must match that exactly.

Then comes bioequivalence. This is the real test. The generic must deliver the same amount of drug into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand. The FDA requires bioequivalence studies showing that the 90% confidence interval for the peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC) of the generic falls between 80% and 125% of the brand. That’s not a guess-it’s a strict statistical standard backed by real patient data.

Finally, clinical equivalence. Even if the numbers look good, the FDA checks if the drug works the same way in real life. For most common drugs-like blood pressure pills, cholesterol meds, or diabetes treatments-the data shows no difference in outcomes. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (like warfarin or levothyroxine), the margin for error is tiny. That’s why some of these drugs still get special attention.

What Do the Letters Mean? A, B, AA, AP, AT

The first letter is always A or B. A = equivalent. B = not equivalent. The second letter tells you the basis of the evaluation. Here are the most common ones:

- AA: Oral solution or powder for oral solution. Used for drugs like levothyroxine.

- AN: Injectable solution. Common for antibiotics or IV meds.

- AO: Oral solution. Often used for pediatric or liquid formulations.

- AP: Powder for injection. Think of drugs reconstituted before use.

- AT: Topical cream or ointment. Important for skin conditions.

These codes aren’t random. They reflect how the drug is absorbed, how it’s made, and how it’s meant to be used. For example, a generic with an AA code for levothyroxine has passed strict tests for consistent absorption in the gut. That’s critical because even small changes in thyroid hormone levels can affect your heart rate, weight, and energy.

Why TE Codes Matter for Patients and Pharmacists

Every year, over 6 billion prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generic drugs. About 90% of those are TE-rated. That’s not an accident. It’s because pharmacists trust these codes.

When you walk into a pharmacy, the system automatically checks the TE Code before swapping your brand for a generic. If it’s an 'A' code, the pharmacist can substitute it without asking you or your doctor-unless your doctor specifically wrote “Dispense as Written” or “Do Not Substitute.” That’s the law in all 50 states. It’s why your $150 brand-name statin suddenly costs $12.

According to the National Community Pharmacists Association, 91% of pharmacists report high confidence in substituting TE-rated generics. Pharmacy technicians say verifying the code adds less than 30 seconds to each prescription. That efficiency saves time, money, and reduces errors.

Patients, too, mostly notice the savings. GoodRx data shows a 4.7 out of 5 rating for TE-rated generics used for chronic conditions like hypertension and diabetes. But here’s the catch: 12.7% of patients report feeling different after switching-even when clinical tests show no difference. That’s not always about the drug. It’s about packaging, size, color, or even the placebo effect. But for drugs like atorvastatin or metformin, studies like the 2021 JAMA Internal Medicine analysis confirm: no difference in LDL levels or blood sugar control.

Where TE Codes Fall Short

TE Codes are powerful-but they’re not perfect.

First, they don’t cover single-source generics. If only one company makes a drug, the FDA doesn’t assign a TE Code. That’s why some older or niche drugs still carry high prices.

Second, complex products like inhalers, topical steroids, and injectables are harder to evaluate. In 2019, the FDA withdrew TE ratings for several generic budesonide inhalers because they didn’t deliver the same amount of medicine to the lungs-even though they met the bioequivalence numbers. That’s because delivery devices matter. A pill’s absorption is predictable. An inhaler’s isn’t.

Third, TE Codes don’t account for individual differences. Someone with a sensitive metabolism, liver disease, or multiple medications might react differently to a generic-even if it’s rated 'A.' That’s why doctors sometimes avoid substitution for drugs like warfarin, despite identical TE ratings. Patient reports on Drugs.com show 87 complaints about switching warfarin generics, even though studies don’t show a clear pattern of harm.

Dr. Jerry Avorn from Harvard puts it bluntly: TE Codes oversimplify equivalence for certain drugs. He’s right. But the FDA agrees. In their 2022 guidance, they acknowledged that TE evaluations are product-specific and don’t guarantee equivalence in every clinical scenario.

How TE Codes Compare to Other Countries

The U.S. system is unique in its precision and legal integration. In Europe, the EMA doesn’t use a coding system. Each country decides on substitution independently. In Canada, there’s a similar concept, but no standardized code. In Germany, doctors-not pharmacists-control substitution.

The U.S. model works because it’s tied to state laws. Every pharmacy system, insurance formulary, and hospital protocol uses the Orange Book as the final authority. That’s why you can get the same generic in New York, Texas, or Oregon without confusion.

What’s Next for TE Codes?

The FDA is expanding the system. By 2024, they plan to introduce TE Codes for biosimilars-complex biologic drugs like insulin or Humira generics. They’re also testing real-world data from electronic health records to supplement lab studies. That could help catch subtle differences in how generics perform outside the lab.

Right now, TE-rated generics make up 90.1% of all prescriptions. By 2027, that number is expected to hit 93.4%. The Congressional Budget Office estimates TE Codes will save $1.2 trillion between 2023 and 2032. That’s not just a number. It’s more people getting their meds, fewer people skipping doses because of cost, and less strain on the healthcare system.

How to Check a TE Code Yourself

You don’t need a pharmacy degree to look up a TE Code. The FDA’s Orange Book is free and online. Just search the drug name or active ingredient. If it’s listed with an 'A' code, you can safely substitute. If it’s 'B,' ask your pharmacist why.

Most pharmacy software-like Epic or Cerner-shows the TE Code right on the screen when a prescription is filled. But if you’re curious, you can check before you pick up your prescription. The American Pharmacists Association even has a free TE Code app with over 50,000 downloads.

And if you’re switching generics and feel off? Tell your pharmacist. It’s not always the drug. But it’s worth checking.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all generic drugs rated with a TE Code?

No. Only multi-source drugs-those with more than one manufacturer-are assigned TE Codes. Single-source generics, brand-name-only drugs, and some complex products like inhalers or biologics may not have a code. The FDA only evaluates drugs approved under the ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application) pathway, which covers most generics.

Can I ask my pharmacist to give me the brand instead of the generic?

Yes. If your doctor writes "Dispense as Written" or "Do Not Substitute" on the prescription, the pharmacist must give you the brand. You can also request the brand at the pharmacy counter, though your insurance may charge you more. Some people do this if they’ve had a bad reaction to a generic, even if the TE Code says it’s equivalent.

Why do generic pills look different from the brand?

By law, generics can’t look exactly like the brand-that’s to avoid confusion and trademark infringement. They must have different color, shape, or markings. But the active ingredient, strength, and dosage form must match. The difference in appearance doesn’t affect how the drug works.

Are TE Codes the same as bioequivalence?

Bioequivalence is part of TE evaluation, but not the whole thing. Bioequivalence means the drug enters your bloodstream the same way. Therapeutic equivalence adds clinical outcomes: does it work the same in patients? Does it have the same safety profile? Two drugs can be bioequivalent but still not be therapeutically equivalent if they have different inactive ingredients that affect absorption.

Do TE Codes apply to over-the-counter (OTC) drugs?

No. TE Codes only apply to prescription drugs reviewed by the FDA under the Orange Book. OTC drugs are regulated under different standards, and substitution is based on labeling and active ingredients, not formal TE ratings.

How often is the Orange Book updated?

The FDA updates the Orange Book monthly. New TE Codes are added as generics are approved, and existing codes are revised if new data emerges. Pharmacists rely on real-time updates in their pharmacy systems, but the public can check the latest version on the FDA’s website.

Final Thoughts

Therapeutic Equivalence Codes are one of the quietest, most effective tools in modern medicine. They’re not flashy. They don’t make headlines. But they’re why millions of Americans can afford their heart meds, their insulin, their antidepressants. The system isn’t flawless. It struggles with complex drugs and patient perceptions. But when it works-as it does for most common prescriptions-it saves lives and money without sacrificing safety.

Next time you get a generic, check the TE Code. If it’s an 'A,' you’re getting the same medicine, just at a fraction of the cost. And that’s not just smart pharmacy-it’s smart healthcare.

Write a comment

Items marked with * are required.

11 Comments

Stacy Tolbert December 10, 2025 AT 03:38

I switched my levothyroxine to a generic last year and felt like a zombie for two weeks. Like, zero energy, brain fog, crying at commercials. My doctor said it’s ‘equivalent’ but my body said otherwise. Now I pay out of pocket for the brand. Worth every penny.

Also, why do they make generics look like candy? My pill looks like a Pepto-Bismol toy. I don’t trust it.

And don’t get me started on the color changes. One month it’s blue, next month it’s purple. My anxiety goes up just seeing the bottle.

It’s not just the drug. It’s the whole damn experience.

People act like it’s just a pill, but your body remembers.

I’m not anti-generic. I’m pro-not-being-terrified-of-my-meds.

Also, why do pharmacies always pick the cheapest one? Like, can’t they pick the one that doesn’t make me want to crawl into a hole?

My pharmacist just shrugs. ‘It’s an A code.’ Yeah, but my soul’s on a B.

Anyway. I’m just saying-don’t assume equivalence means ‘feels the same.’

And if you’re lucky enough to afford the brand? Don’t feel guilty. Your health isn’t a budget line item.

Also, I miss the old blue pills. They were cute.

Anyway. Thanks for the post. At least someone’s talking about this.

Ryan Brady December 11, 2025 AT 12:44

USA still the only country that actually gives a shit about drug quality. Europe? They let anything pass as long as it’s ‘close enough.’

Meanwhile, we got a system that’s so tight, even the inactive ingredients get audited.

And yeah, some people whine about color changes. So what? It’s not the pill, it’s your brain.

Also, if you can’t afford the brand, you’re not poor-you’re lazy. Get a job.

TE codes = American genius. 🇺🇸😎

Raja Herbal December 12, 2025 AT 23:01

Oh wow. So the FDA gives a gold star to generics… but in India, we just get whatever the distributor ships. No codes, no transparency. Sometimes the pills look like they were made in a garage.

And yet, people here take them without a second thought. Funny how trust works, huh?

Meanwhile, Americans have a 10-page manual just to swap a blood pressure pill.

Which is better? I don’t know. But I’m glad I’m not paying $150 for a statin.

Also, the ‘AA’ code for levothyroxine? That’s the one my cousin in Ohio had to switch from. She cried. Not because of the drug. Because the new pill had a different smell.

Psychology is wild.

Anyway. Your post made me feel like I’m living in a sci-fi world where pills have barcodes and souls.

Still, 90% of my meds here work fine. So… maybe we’re all just lucky?

Or maybe we’re all just pretending.

Iris Carmen December 13, 2025 AT 14:09

so i just found out my metformin changed color again?? like, one day it’s green, next day it’s white?? and the shape? totally different. i thought i was getting scammed until i checked the te code and it was still ‘ap’.

also, why do they make the pills so tiny now? i have to use tweezers to swallow them. my grandma would’ve had a stroke.

but hey, it’s $3 instead of $80 so i’m not complaining. just… weird.

also, my pharmacist says ‘it’s the same thing’ but my poop is different. so… yeah.

also, why is the bottle always louder than the last one? like, is the plastic getting thinner? or is my hearing getting worse?

anyway. te codes are cool. i just wish they’d put a ‘feel’ rating on them. like, ‘this one might make you cry at the grocery store.’

Rich Paul December 14, 2025 AT 09:04

Let’s be real-TE codes are just the FDA’s way of saying ‘we did the math, now shut up.’

Bioequivalence? 80–125% Cmax/AUC? That’s not equivalence, that’s a fucking range. You’re literally saying ‘close enough’ and calling it science.

And don’t get me started on the ‘clinical equivalence’ part. You test on 50 people for 12 weeks and call it ‘real world’? LOL. Real world is 78-year-old diabetics on 8 meds with liver cirrhosis. You think your model captures that?

Also, ‘A’ code doesn’t mean ‘identical.’ It means ‘not worse than 20% off.’

And yeah, the Orange Book is updated monthly. But your pharmacy’s software? Still cached from 2021.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘single-source’ loophole. That’s how Big Pharma keeps pricing gouging alive.

TE codes are a band-aid on a hemorrhage.

But hey, at least they’re better than nothing. I guess.

Also, the app you mentioned? It crashed when I tried to look up my insulin. Classic.

So yeah. The system’s flawed. But it’s the best we got. And that’s the saddest part.

Delaine Kiara December 14, 2025 AT 09:59

Okay, I’m not saying I’m a genius, but I’ve been on 12 different generics for my antidepressants since 2018, and I’ve kept a spreadsheet. I swear to god, I’ve got graphs. I’ve got notes. I’ve got mood swings logged by pill color.

One brand? Made me cry during a TikTok of a dog wearing sunglasses.

Another? Made me feel like a robot who just won the lottery.

One? Gave me a rash. Like, full-on hives. I thought I was allergic to the pill. Turns out, it was the dye. The dye, y’all.

And guess what? All of them had an ‘A’ code.

So here’s my hot take: TE codes are for the system. Not for the person.

My doctor doesn’t care. Insurance doesn’t care. Pharmacists say ‘it’s the same.’

But my brain? My brain remembers.

I’ve switched back to brand name twice. Cost me $200 a month. Worth it.

Also, I named my pills. The blue one is ‘Bobby.’ The white one is ‘The Ghost.’

And yes, I’m aware this sounds insane.

But if you’ve ever felt ‘off’ after a switch, you know what I mean.

Also, my therapist said I have ‘medication attachment disorder.’ I told her she should write a paper on it.

Anyway. TE codes are fine. But they don’t know my soul.

And that’s the real tragedy.

Ruth Witte December 15, 2025 AT 14:15

YAS QUEEN 🙌 TE CODES ARE THE REAL MVP 🌟

My blood pressure med went from $140 to $4. I’m not crying, you’re crying. 😭💖

And guess what? My numbers are BETTER. Like, I’m basically a walking health influencer now. 💪

Also, I love that I can check the code myself. Feels like I’m a detective. 🔍💊

And the Orange Book app? I use it while waiting in line at Target. It’s my new hobby.

PS: My pharmacist gave me a sticker for using generics. I framed it. 🏆

Stop hating on generics. They’re the unsung heroes of healthcare. 🥹❤️

Also, I switched my levothyroxine and felt like a new person. Like, I can finally do yoga without crying. 🧘♀️✨

TE codes = freedom. 🇺🇸✨

Noah Raines December 16, 2025 AT 14:49

My dad’s on warfarin. Switched generics. INR spiked. Went to ER. Turned out the generic had a different filler. Didn’t affect bioequivalence, but messed with absorption in his gut.

TE code was still ‘A.’

So yeah. The system works… until it doesn’t.

And when it doesn’t? You’re the one paying the price.

Pharmacist didn’t even blink. ‘It’s an A code.’

So now we pay cash for the brand. $180/month. Worth it.

Also, the FDA’s ‘clinical equivalence’ is a joke. You test on healthy people. My dad’s 78 with diabetes, heart disease, and a bad kidney. He’s not in your study.

So don’t act like this is flawless. It’s not.

But hey, at least we’ve got a system. I’ll take it.

Still… scary.

Also, why does every generic look like it was made by a robot with a grudge?

Katherine Rodgers December 17, 2025 AT 13:05

Oh wow. So the FDA gives a gold star to generics that are 80–125% as effective as the brand and calls it ‘equivalent’?

That’s not science. That’s corporate math.

And you think patients don’t notice the difference? Please. We’re not idiots. We’re just broke.

Also, ‘AA’ code for levothyroxine? That’s the one that makes people lose hair, gain weight, and feel like they’re slowly turning into zombies.

And yet, pharmacists swap it like it’s a coupon.

Meanwhile, the brand? Costs $180. Insurance says ‘nope.’

So you’re telling me the system’s ‘fair’ because the math checks out?

But the person? The actual human? Doesn’t matter.

Also, ‘TE codes save $1.2 trillion’? Cool. But who’s paying for the ER visits, the therapy, the lost jobs because they couldn’t focus?

It’s not a win. It’s a trade-off.

And the FDA? They’re not protecting patients.

They’re protecting the system.

And we’re the collateral.

Also, I’ve been on 7 different generics for my thyroid. I’ve lost 3 pounds. Gained 5. My hair’s falling out. My anxiety’s through the roof.

But hey. It’s an ‘A.’

So I guess I’m lucky.

Right?

Right.

…

Lauren Dare December 18, 2025 AT 19:11

Let’s not romanticize TE codes. They’re a regulatory tool, not a clinical guarantee.

Yes, they standardize substitution. Yes, they reduce costs. But they don’t account for pharmacogenomics, gut microbiome variability, or polypharmacy interactions.

And the ‘A’ designation? It’s based on population averages. Not individual outcomes.

So when a patient reports ‘I feel different,’ dismissing it as ‘placebo’ is not just unscientific-it’s unethical.

Also, the FDA’s reliance on bioequivalence for complex products like inhalers and topical agents? That’s a regulatory gap dressed as progress.

And don’t get me started on the ‘single-source’ loophole. That’s not a flaw-it’s a feature for Big Pharma.

TE codes are necessary. But they’re not sufficient.

And if we treat them like gospel, we’re not saving lives.

We’re just optimizing profit margins.

Also, the Orange Book is free. But the information isn’t accessible to most patients.

So yes. We have a system.

But it’s not designed for us.

It’s designed for the system.

And that’s the real tragedy.

Gilbert Lacasandile December 19, 2025 AT 04:55

I just want to say thank you for writing this. I’m a pharmacy tech and I see this stuff every day.

Most people don’t realize how much work goes into checking TE codes. We don’t just swap pills. We verify, cross-reference, sometimes call the prescriber.

And yeah, sometimes a patient comes in upset because their pill changed color. We don’t judge. We listen.

And sometimes, they’re right.

I’ve had patients who swear their new generic made them dizzy. We check the code, it’s ‘A.’ But we still call the doctor and say ‘maybe try the old one.’

Because even if the science says ‘equivalent,’ the human says ‘not for me.’

And that’s okay.

TE codes are a tool. Not a rule.

And I’m glad someone’s talking about it.

Also, the app you mentioned? We use it at work. It’s saved us from a few mistakes.

Thanks for the post. It made my day.

Also, I just got my own generic for blood pressure. It’s blue. I like it.

And it’s $4. I’m not complaining.

But I still check the code. Every time.